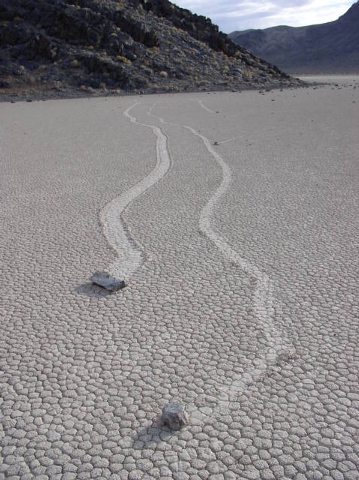

DEATH VALLEY —Scientists in Death Valley National Park believe they have solved the mystery of the Racetrack Playa. This mystery involves rocks that mysteriously move by themselves on a dry lake bed. The lake bed is located in a remote valley between the Cottonwood and Last Chance ranges.

Visitors have come to the playa since the 1940s and have seen rocks and even boulders with tracks behind them. Some of the boulders were as large as 700 pounds. The tracks indicate that the rocks were dragged across the ground. The rock trails would sometimes be hundreds of meters long.

Researchers have been investigating for years. No one has actually seen the rocks move until recently.

A team led by Scripps Institution of Oceanography published their findings on a study of the rocks, which started in the winter of 2011. UC San Diego paleobiologist Richard Norris reported on his first-hand observations on Wednesday. No one on the team expected to witness the phenomenon first hand because rocks were known to stay stationary for as long as 10 years or more.

Co-author of the paper, James Norris, went to the playa on Dec. 13, 2013 two years after the study started. After he arrived he found the playa covered with a shallow pound, which was no more than seven centimeters deep. To his shock, the rocks began moving. Another investigator, Richard Norris, also saw the rocks move. “Science sometimes is luck. We expected to wait five or ten years for movement, but only two years into the project, we just happened to be there to see it in person,” Richard said.

The team monitored the rocks remotely through a high-resolution weather station. The station was able to measure gusts to one second intervals. They fitted 15 rocks with custom-built, motion-activated GPS units.

These rocks were outside rocks because the National Park Service didn’t let them touch the current rocks that were there. They set this experiment up in 2011 with the permission of NPS.

They discovered that to get the rocks moving takes a rare combination of events. The playa needs water, which must be deep enough to allow floating ice to form. The water can’t cover the rocks. It must be shallow enough to expose the rocks. During the night, “windowpane ice” forms. This ice must be able to move freely, but also strong enough so it does not break apart in the wind. When the sun comes out, the sun melts the ice and then the smaller sheets are blown by light winds. The ice pushes the rocks in front of them and in turn the rocks leave a trail in the soft muck. “On December 21, 2013, ice breakup happened with sounds coming from all over the frozen pond surface,” said Richard. “I told Jim, ‘This is it!’”

Previous ideas had the rocks moving due to fierce winds, dust devils, slick algal films, or thick sheets of ice. The team saw the rocks move under various conditions and not all of them involved high wind conditions. The team observed rocks moving in light wind conditions of 10 miles per hour. The rocks were propelled by sheets of ice less than .25 inches thick. Those sheets were too thin to move the bigger rocks. The rocks would move only 2-6 meters per minute. This was too slow for the naked eye to pick up without a good reference point. The rocks would move from seconds up to 16 minutes. The longest movement recorded was 200 feet.

So does this mean the mystery is solved?

“We documented five move events in the two and a half months the pond existed,” Richard said. “Even in this place famous for its heat, floating ice is a powerful force driving rock motion.” He added that, “We have not seen the really big boys move out there … does that work the same way?”

The National Park Service contributed to this article.