Nearly 30 years after Belgian artist Albert Szukalski created his “Last Supper” sculpture at Rhyolite and set in motion what would become the Goldwell Open Air Museum that would later include the work of three other Belgians, the organization announced its hosting yet another Belgian artist.

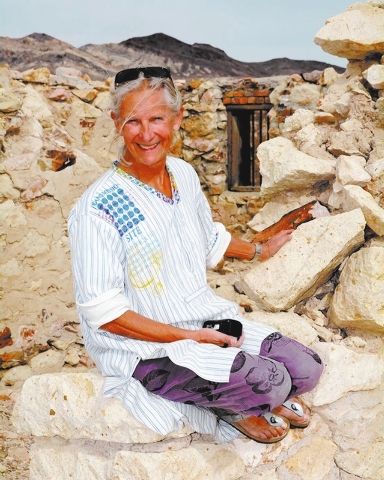

Cecile Massart came to Goldwell late in October for a two-week residency, working on an unusual project of international scope and importance.

Massart has long been concerned with the idea of how to preserve and pass on memories.

Seeing the evolving technology of recording technologies as the world went, for instance from video tape to CD, she wondered if memories or information would be lost that were recorded in now obsolete forms.

And what about the way even common symbols change meaning over time? Languages themselves change. For instance, how many Americans today struggle with the English of Shakespeare, much less that of Chaucer or of the “Beowulf” poet?

Massart sees this as a major challenge for nuclear waste repository sites. How can the memory of what is buried there be preserved for the generations that will live in the millennia during which the material will be dangerous? How can the sites be marked so that the language, markings or symbols will still be understood?

She sees the answers to these questions as critical for the safety of the future living world.

Back in the 90s, Massart began her current project, which includes what she refers to as “artistic research.” She proposes a multi-disciplinary “laboratory” to bring together scientists, artists, writers, architects, sociologists, and philosophers to collaborate and work with stakeholders, agencies, communities and international bodies on the problem of marking these sites and preserving the memories of what lies there.

As part of the project, Massart has visited repository sites around the world designing site-specific architectural markers to identify them. She describes these markers as “multilayered artistic devices built above-ground through the implementation of a specific architectural vocabulary with codes, symbols and signs that evolve with time.”

The proposed Yucca Mountain repository is what brought Massart to Nevada. She has previously visited and done designs for sites in France, Portugal, Belgium, Spain, Japan, India, Sweden, and Brazil.

Even though Yucca Mountain is currently halted, Massart says it is a very special site for her. She describes it as “mythical” because it is a mountain is in the desert, is in the United States, and is close to the Nevada Test Site. She says that there are “complex issues at stake” that make the site very attractive to her.

When she first arrived for her residency, Massart, who is partially sponsored by the Belgian Ministry of Culture, was given a tour of Yucca Mountain. She and her assistant Anne Marquet also visited the Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas.

The Department of Energy scientist who took her on the tour also explained the geology of the site and of the region as they toured the desert.

“It was striking for a Belgian artist to be here,” said the French-speaking Massart, with Marquet interpreting. “It is so desert, so different from where I live.”

She said she found the people of Beatty to be “very nice, ready to talk and help.”

At the Red Barn Art Center and Rhyolite, Massart worked on a design and maquette of the marker for Yucca Mountain. She will also produce an artist’s book.

Meanwhile, her assistant, who is a third-year art student in painting, worked on a series of abstract landscapes inspired by the colors and textures of desert geology.

Massart has had a long career as an artist, with many solo and group exhibitions around the world, and has produced artist’s books. She taught printmaking for many years and is an expert in the techniques of engraving.