Desert tortoise deaths raise concerns as solar farms solve energy need

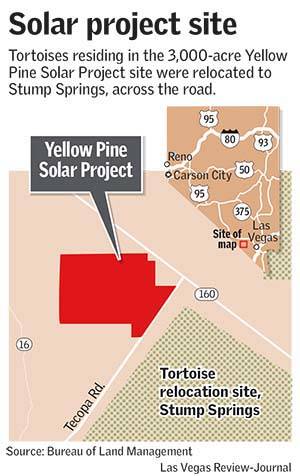

A few miles off the intersection of state Route 160 and Tecopa Road, about 10 miles south of Pahrump, lies a 3,000-acre solar farm under development. As you approach the project, bundles of metal fencing are prepped to soon become 10 miles of temporary desert tortoise exclusion fencing.

A team of biologists relocated 139 tortoises from their habitat to make way for the solar panels in the Yellow Pine Solar Project, one of four large solar energy developments initiated in Southern Nevada. The tortoises were moved across the road to Stump Springs in May.

In a span of a few weeks, 30 tortoises were killed, possibly by badgers. Conservationists believe relocation stress made the reptiles more vulnerable and drought caused badgers to look for new sources of prey. Wildlife experts are still looking into the exact cause.

The loss of the tortoises, a threatened species in Nevada since 1990, illustrates the challenges of bringing alternative energy sources to the Mojave Desert while still protecting its biodiversity.

Conservationists say the state should modify desert relocation protocols under the current drought. Laura Cunningham, biologist and co-founder of Basin and Range Watch, said the tortoises get lost and confused when moved from their home range.

“We’re not even surprised that badgers discovered these tortoises,” said Cunningham. “They have a home range. They dig their own burrows with long claws. They actually dig little scrapes in the desert where rainwater will collect and they drink out of these little rainwater pans. They have particular bushes, they like to go and take a rest and shade. So they really know their area. And when you move them to a different area, they tend to start wandering around and try to get back to their home range, and that’s when they’re taken by predators.”

Cunningham founded the nonprofit Basin and Range Watch with partner Kevin Emmerich 12 years ago. Cunningham and Emmerich were field biologists for state and federal wildlife agencies before shifting their work to help conserve the deserts of Nevada and California while advocating for sustainable, renewable energy alternatives. Both are concerned about the large solar project and its impact on the desert landscape.

“During the drought, there are less rodents, less lizards, and so they [predators] are going after everything. And so we think this was predictable enough that it shouldn’t have been done, especially during a drought,” said Cunningham.

Steven Stengel, a spokesperson for NextEra Energy Resources, declined to comment in an email, saying it was a little early in the project to do an interview, and “they would be happy to do so when it was further along.”

The solar project

Through the Public Land Renewable Energy Development Act, the federal government is incentivizing wind, solar, and geothermal energy developments on public lands.

In November 2020, the Bureau of Land Management accepted the Yellow Pine Solar Project application. Developed by a subsidiary of NextEra Energy Resources, Yellow Pine is expected to generate 500 megawatts of electricity for up to 100,000 households using photovoltaic solar panels by the end of 2022.

The solar arrays absorb energy from the sun and generate electricity, which would then be stored in a lithium-ion-based battery, gathered by an internal electrical collection system, and then transformed to transmission voltage before reaching homes.

The developers say the solar farm will provide local employment opportunities, including 300 construction jobs and approximately $23 million in additional tax revenue for Clark County within a decade of the project.

Before development, the company first surveyed the wildlife, vegetation, cultural and tribal resources, and endangered species. BLM then issued a right-of-way in January 2021, granting the developers approval to begin clearing out the area of tortoises and putting up exclusion/security fencing to keep the tortoises from wandering back into the project site.

Tortoise mitigation

There are strict guidelines and standardized protocols in place, set by the Fish and Wildlife Service, for each phase of handling the tortoises to mitigate risks and prevent further endangering the species.

The desert tortoise has been listed as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act because of population decline due to predation, collection by humans, off-highway vehicles, and upper respiratory tract disease.

In addition, urban developments, agriculture, road construction and military activities have fragmented tortoise habitats, reducing the tortoise population below the level necessary to maintain a minimum viable population.

“We have even better data now to show that the populations are, well, they’re not quite stable,” said Todd Esque, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. “And so that’s concerning that even after it’s been, what, 30 years now? We knew when they got listed that it would take decades to get them turned around. But we have to be able to do all the things that that requires, to turn them around; you can’t just wish they would start repopulating.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service monitors tortoise populations in designated conservation areas throughout the range, including Southern Nevada, Southern California, southwestern Utah and northwestern Arizona. However, tortoises outside designated conservation areas are not monitored and mostly inhabit the land renewable energy developers are interested in.

During the survey, the number of adults, juveniles and hatchlings is counted in three areas by qualified consultants: the project area, the relocation area and a reference site in a conservation area.

Consultants check the health status of the tortoises in the project and relocation site to prevent disease spread and finally, the relocated tortoises are paired with a tracking device. The developers report back to both BLM and state wildlife officials throughout the process.

Despite mitigation measures, within weeks of relocating the tortoises from the project site to their new home in Stump Springs, dozens died.

“I think most of those were thought to be from or had signs of badger predation,” said Roy Averill-Murray, desert tortoise recovery coordinator for the Fish and Wildlife Service. “Others could have also included a small handful of other natural causes, but it seemed to be mostly this kind of localized focus badger attention on the translocated tortoises.”

The tortoise deaths from badgers accounted for roughly one-third of the relocated adults. No more deaths have been reported since the incident took place from mid-May to mid-July.

“So not sure exactly what that badger was doing, or what’s going on, but it was pretty focused on that five-week period and just stopped,” said Averill-Murray.

Badgers aren’t typically known to prey on desert tortoises. Instead, their main prey is desert rodents, but they are also known to eat ground-nesting birds, lizards, and insects.

They also aren’t the only desert animals with a history of switching prey.

Other tortoise relocation

Esque and Averill-Murray were part of a study in 2008 that looked into the relocation of 2,000 tortoises from Fort Irwin in Southern California, where hundreds of square kilometers of habitat were cleared for Army tank training.

In their research, 600 tortoises were radioed from three subpopulations: one group nowhere near any of the animals that got moved, one group living in the area where the tortoises got moved, and then the group that got moved.

Coyotes attacked all three tortoise populations near the area. According to Esque, it’s difficult for a coyote to eat tortoises because they require more energy to eat than the rabbits that coyotes typically prey on. But during drought, if rabbits die out, coyotes will resort to eating tortoises, which is what happened in Fort Irwin.

“So the story was not that there’s one thing happened, and they moved tortoises, and they all got whacked,” said Esque. “It’s that, the whole desert — now the way we’ve set it up with our towns across the desert — we’ve set it up so there are patches where it’s a higher risk to be a tortoise when you’re near a town. And that’s the bad news. For tortoises, it was much bigger [risk] than just an incident of moving the tortoises in one time.”

For their Fort Irwin study, it was not the act of translocating the tortoises that led to their death, but how much more residential areas are blending into wildlife where many predators reside. Comparing the badger instance to the coyotes changing their prey toward tortoises, it’s difficult to also claim that drought was the main culprit.

“It’s really hard to know what’s going on,” said Averill-Murray. “Why, if it was related to the drought, why aren’t coyotes eating tortoises in Stump Springs? It’s just very strange and it’s not quite as simple as, ‘Oh, it’s drought and the predators automatically eat translocated tortoises. Or translocated tortoises are more susceptible to being eaten by predators in a drought.’ It’s just that has not been the case over the last 10-15 years.”

Tortoise vs. solar

Cunningham and Emmerich propose that developers instead build solar arrays on the tops of parking garages, or push back the development of solar projects when there isn’t an extreme drought.

“We’re asking the tortoise to make a sacrifice here for climate change. Maybe we the people, in the city and towns, should really try to conserve more and make our structures more energy-efficient and less wasteful,” said Cunningham.

Developers of the Yellow Pine Solar Project need to finish setting up the tortoise exclusion fence before moving on to the next stage of development later this year.

For now, they are responsible for keeping track of all three populations of the desert tortoise for a full year. After that, according to Averill-Murray, the developers will hand off the project to the Fish and Wildlife Service, which will most likely contract out the U.S. Geological Survey to continue monitoring the tortoises.

“BLM is having them [developers] pay a fee to support monitoring into the future. I think it’s a $1 amount per acre that they’re developing [fee] that they’re putting into a bank account that will support the future monitoring down the line,” said Averill-Murray.

The Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service partnering with the U.S. Geological Survey allows for the long-term monitoring of translocated desert tortoises to inform future mitigation protocols.

“Judging by the number of applications we have for solar plants, basically, the next area will be between Las Vegas and Beatty, Nevada — a giant flat valley up there that’s all perfect for solar. But that’s also one of the few north-south corridors for desert tortoises to respond to climate change if they need to if we can think in those terms, which is really long terms,” said Esque. “So what should the strategy be for that? Not just for our backyard here, but the whole range of desert tortoises.”

Stephanie Castillo is a 2021 Mass Media reporting fellow through the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Email her at scastillo@reviewjournal.com or follow her on Twitter @PhutureDoctors.