The Beatty Brothels —

Red Rooster and Willow Tree

By the early 1950s, most of the mines in the Beatty area had closed. But a major new economic force was taking shape in the area that would mean greater prosperity for all of southern Nevada.

On Dec. 18, 1950, President Truman approved establishment of an atomic testing facility on part of the Las Vegas-Tonopah Bombing and Gunnery Range. On Jan. 27, 1951, the first atomic device was set off on the Nevada Test Site. Headquarters for the new facility were located 40 miles south of Beatty at Mercury.

Nuclear weapons testing meant jobs for Beatty residents and increased traffic on U.S. Highway 95 linking Beatty with Las Vegas, Tonopah, and Reno. Large numbers of well-paid workers parked their trailers in Beatty and commuted to jobs on the Test Site.

Beatty business prospered with a half a dozen bars and gambling casinos, five gas stations, and a handful of cafes and motels. Local residents report there were also up to seven brothels in the Beatty era during this period.

Keep in mind, Beatty at this time was only 45 years removed from the glory days of Rhyolite. Among the brothels were Bailey’s Hot Springs, located north of town, and one by the Beatty airport.

Two brothels, the Red Rooster and the Willow Tree, located within the town of Beatty, operated until 1957. The Willow Tree was constructed of concrete blocks and painted pale green.

It was described as resembling a small motel or an expensive, one-story desert home. There was a large electric sign on the roof facing town that read “Willow Tree.” A small “carefully nurtured willow tree” grew on the patio. On the eaves were strung alternating red and yellow light bulbs. A red light bulb was affixed to a porch light.

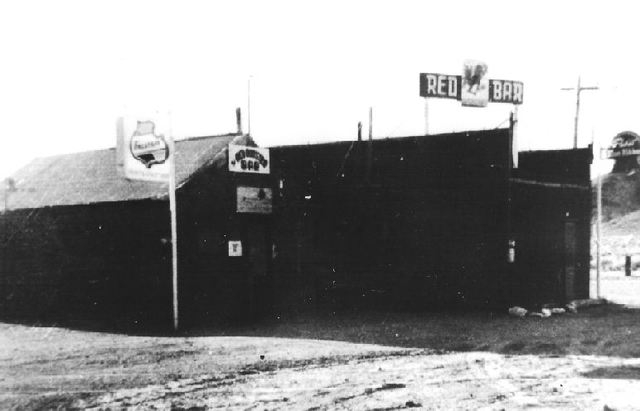

The Red Rooster was a two-story box-like structure covered with red tar paper. It featured a couple of neon signs reading, “Red Rooster Bar.” An uncovered red light bulb announced the joint’s purpose.

Each brothel was said to have averaged about five girls and at one point charged $5, $7.50, and $10 depending on the party (i.e., activity) preference. Each house was said to net between $7,000 and $8,000 a month. Moreover, the houses were said to have operated with “no interference from county authorities—the Nye County Board of Commissioners or the District Attorney” or, of course, the state.

County authorities were located in Tonopah and if the brothels followed a few basic rules set down by the commissioners and there were no citizen complaints, they were operating fully within the law (Guy Shipler, Jr. “The Town That Fought to Keep Prostitution,” True Magazine, November 1965, p. 42).

Most Beatty residents spoke positively of the women working in the two brothels. One middle-aged man said both establishments were “as clean as your own bedroom.” He said the girls were well-behaved and never used vulgarity.

Beatty Brothels Close

Things changed in the fall of 1957. Nye County District Attorney William Beko ordered both the Red Rooster and the Willow Tree closed. No reasons were given and there was no indication as to whether the closures would be permanent. To say that the town’s leading citizens were surprised is an understatement.

Proponents drove to Tonopah “at top speed”—there was no speed limit on the open roads in Nevada at that time—to find out the reason.

In Tonopah, Beko informed them that three people had complained to the effect “that one of the madams got drunk one night and went outside and began shouting the names of her customers at the top of her lungs” (Shipler, pp. 42 and 78). Beko also indicated that there were reports from reliable sources that the girls were not getting their weekly physical examination as required and some had not been fingerprinted. The former was intended to help control disease; the latter was for control of white slavery.

There were also charges that the lights on the Red Rooster and the Willow Tree were too bright and the establishments stood too close to the highway. In addition, children used a vacant lot across from the Willow Tree for a playground. Additionally, more of the girls were being seen uptown.

This decision did not sit well with many of Beatty’s citizens. A petition was circulated and signed by 144 people, with 44 of the signers women, none of them prostitutes. The petition stated: “We the undersigned citizens and residents of Beatty, Nevada, and vicinity do hereby protest the closing of the two business houses operated by Francis Hardy and Belle Norheim, commonly known as the Willow Tree and the Red Rooster.”

Supporters of legal prostitution contended that efforts to eliminate the ancient practice through legal prohibition were similar to unsuccessful efforts to prohibit the sale of alcohol earlier in American history. Most rural Nevadans believed it was better to have prostitution out in the open where they could control it rather than operating underground where they couldn’t.

That’s one of the reasons Nevada legalized gambling. Why not legalize prostitution?

District Attorney Beko explained that he was not opposed to prostitution, at least in principle. But, he suggested, it was getting out of hand in Beatty. He said, “When I heard about the drunken madam and about the girls not getting their physicals, that was it. I decided to close down the houses for 30 days—sort of a punitive measure to get things back in line.”

Beko explained that he acted under Nevada’s nuisance laws, defining a nuisance as “anything which is injurious to health or indecent or offensive to the senses.” He noted he didn’t have enough evidence to make the shut-downs permanent. The complaints provided no real evidence that prostitution was going on at the two establishments.

Ironically, the petition protesting the closure of the brothels provided that evidence. In his 1965 article on the Beatty brothels, Guy Shipler suggests that it was that petitions protesting the shutdown “that permanently sealed the doom of the Red Rooster and the Willow Tree.”

The complaints had not been proof of prostitution but the petition had.

Shipler writes, “Beko sighed. ‘It was really too bad,’ he said. ‘Prostitution could mean good business for the town.’” But Shipler points out that there was another dimension to it. Prostitution was more than an economic benefit to Beatty. Beko said, “The citizens of Beatty are for prostitution on moral grounds.”

Beko indicated that that showed up in the petition. He said, “You can’t have a thing like that, which decent women will sign, unless the women are sincere about it. So when a town obviously wants prostitution, we have to listen.”

At one point, Shipler did an informal survey of public opinion regarding prostitution in Beatty. He talked to the bartender at the Exchange Club, Beatty’s general meeting place and most important bar and casino at the time. The bartender, described as a “tall, thin man with a mustache,” was eager to speak about the shutdown.

He said, “A couple of weeks ago, before the places closed, three guys come up from Edwards Air Force Base, down in the Mojave Desert in California. Blow into town on Friday night and didn’t leave ‘til Sunday. Before they left, they told me they come down because of them whores. Said they dropped a total of $450 bucks while they were here.”

The bartender recommended Shipler talk to a waitress at the Exchange Club, Mrs. Ruth Hinds, to get a woman’s perspective on the issue. Mrs. Hinds was president of the PTA and active in civic affairs in the community. She said, “I feel there is a definite moral value in having these places. Beatty has no sex crimes. I don’t remember ever hearing of a child being molested.

Now the few women here who didn’t want to sign that petition don’t think that sex fiends go to places like that. Maybe I’m wrong, but I think they do. In any case, we don’t have rape in Beatty.

“I have a 16-year-old boy. I would rather have him go to a place like that than having him bothering a girl. I know he’s going to get the urge, because nature is nature.

“My next-door neighbor feels the same way I do. She has five girls, and now she thinks they should stay home at night because the houses are closed. She’s afraid now her girls might get attacked.” She added, “There has never been a children’s program, or a Christmas program without the Willow Tree and the Red Rooster both having given a big donation.”

The piano player at the Oasis Bar in Beatty indicated that his business dropped 25 percent immediately after the two brothels were closed.

Another man added his opinion. “Other towns could learn a lesson from Beatty. We’re proud of our little community. It’s a cross-section of American life. We got a millionaire or two, a proportionate number of stiffs, and a lot in between, just like anyplace else. Yet there are only a few guys in town who don’t want these joints reopened.”

One man said to have been born and raised in Nevada seemed to summarize the feeling of Beatty residents regarding the closure. He said, “In this town, the right to have legal prostitution is no different than the right to vote. Hell, you don’t have to go to whorehouses, or even approve of them, just like you don’t have to approve of a certain movie or go to bars. But that don’t mean you shouldn’t allow them. We feel a man’s got a right to live like he wants to.”

The Willow Tree and the Red Rooster never reopened. A new brothel opened about two and a half miles north of Beatty and over the years operated under a variety of names.