Marta Becket’s last curtain call

Last Monday on the edge of Death Valley, in a quirky old adobe house filled with extraordinary paintings and stage memorabilia, 92-year-old dancer Marta Becket died as she lived, committed to a dream.

She leaves behind an endowment of art, culture and inspiration for both past and future generations of fans and visitors to her beloved Amargosa Opera House.

Nearly 50 years ago, Becket claimed a windswept and nearly forgotten corner of the desert for her own when she put a dollar down as security on an abandoned old theater in Death Valley Junction. It stood at the end of a sprawling Spanish Colonial hacienda that once housed an entire company town complete with a post office and hospital.

On the outside, the whitewashed adobe auditorium all but blended in with the low hills and bone-colored landscape around it, but inside, over the next seven years, she created a richly colorful alternate reality inhabited by kings and queens, cats and acrobats, magic and make-believe. For 45 years, until her retirement in 2012, she danced on her own stage, with costumes and props of her own creation, telling stories brought to life from her own imagination.

Becket had been on her way to someplace down the road, touring her one-woman dance pantomime show, when her van got a flat tire and her then husband drove it into the Death Valley Junction filling station. It was the summer of 1967 and there were only a few families left in the old railroad town.

While she waited, Becket wandered about until she was drawn down the building’s long colonnade to the door of the old auditorium. Peaking through a dusty window, she saw not the warped floors, the dusty stage curtains, or the holes in the roof, but rather “I was looking at the other half of my life,” she wrote later. Corkill Hall had once been the social center of the town and Becket, who always had an ear for spirits, could almost hear the laughter and applause of residents who’d sat through movies, plays and pageants forty years before.

“The building,” she wrote, “seemed to be saying ‘Take me. Do something with me. I offer you life’…At that moment, for me, the world could have New York. I wanted this theater.”

Marta Becket was born in New York City in 1924 and had lived there almost all her life. Some of her earliest memories were of the theater and becoming aware of the contrast between the staggering beauty of a theatrical performance and the dreary mundanity of everyday life. The magic that happened behind the curtain called to her, she later wrote in her 2005 autobiography “To Dance On Sands,” and she knew that’s where she belonged.

Becket studied art and dance in an eclectic mix of settings as a child, dependent upon her natural and quick talent to win her scholarships. Raised by a reclusive single mother, Becket lived an often hand-to-mouth existence. But as long as she could paint and dance and create her own compositions, the rest of it mattered little. She had always been captivated by grace and style and was driven by a desire to embody classical beauty in her performances.

In her twenties she sold paintings and danced at Radio City Music Hall to support herself and her mother. During those years she was also falling in love with the kind of Vaudeville-meets-classical-ballet dancing she would do for the rest of her life.

“I knew now that dance and pantomime were universal languages in the theater, where tragedy becomes bearable, even beautiful,” she wrote later. “I knew now that this was the language I wanted to speak. I wanted to be a part of that world which had the ability to reflect life back to us so beautifully.”

She began to create her own dance pantomime shows and eventually began touring the country with all her props and backdrops packed into a van piloted by her then husband Tom Williams. And that’s how she landed in Death Valley Junction, on her way to a show somewhere down the road.

At first the locals laughed at her when she told them her plan, but when she and Williams finally had the theater mucked out and had rebuilt the stage, the neighbors came to watch her perform. She held the formal opening of the Amargosa Opera House on Feb. 10, 1968. And she gave her shows every weekend, whether anyone came or note. To pay the bills in the meantime Becket’s husband bartended at a brothel just over the Nevada state line. The madam took an interest in the Opera House and brought the women who worked for her to the show once a month “for culture”.

Sometimes no one came and Becket danced alone, but that didn’t really matter much to her. What mattered was the performance, the art, the creation. In between shows, she spent seven years painting murals of an audience that covered all three walls and the ceiling of her theater. Not because she needed the company, she said, but because the people she painted, representatives of the past, were fitting witnesses to the work she dedicated in their honor.

After a few years, Becket was featured in National Geographic and Life magazines and word spread about the eccentric ballerina in the desert. The Opera House became something of a legend and drew full enough audiences that it allowed her to live for her art and eventually, to take out a loan to buy the whole town of Death Valley Junction.

But even if it had not become a success, Becket wrote, “I would still be here struggling to support my art. This is not because I think my art to be great, it is because my art is so necessary to me.”

And as the years went on, her fearless dedication and her enduring success became an inspiration to others emboldened by her story.

Marta Becket had followed her muse to the edge of a place called Death, where she found the means to truly live her life. The lonely desert never frightened her, she loved the wild things, the water under the moonlight, the nighthawks, the untamed horses that galloped across the brushy desert floor. Most of all, she loved the freedom.

Marta Becket’s husband left Death Valley Junction in the early 1980s and a friend and maintenance man stepped in to become the emcee of her show. Tom Willet, whom she called ‘Wilget’, was handy and helpful, he understood her vision, and he made her laugh. Becket noticed he had the gift of making others laugh, too, so she put him in a tutu and included him in her shows. Willet, she said, was her ‘soulmate’, especially because he never pressured her to marry or to put him above her art. He loved the life they lived as much as she did.

Becket and Willet performed together until his death in 2005 and then she continued solo.

Thousands of times over the 45 years she danced at the Amargosa Opera House, until her retirement in 2012, Becket drew her audience into another world and awed them with her power to make that world come alive.

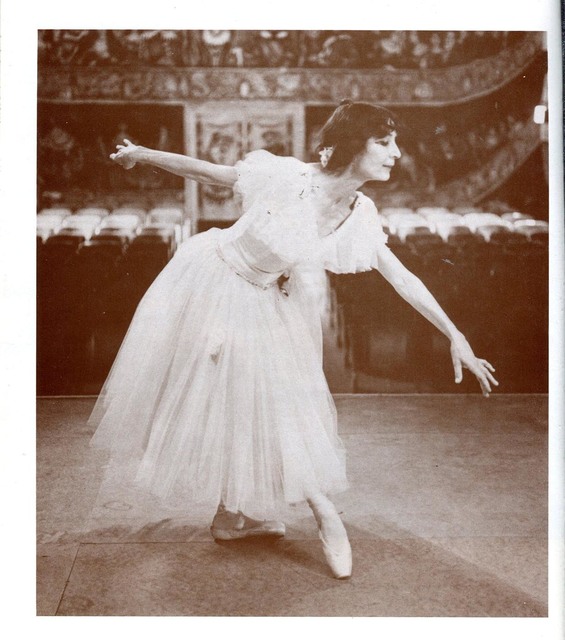

She danced on pointe until well past the age of 80 and moved with grace and patrician elegance all of her life. Off stage in later years she seemed rather frail, beset by worries about the finances of the crumbling adobe of the behemoth Amargosa Hotel, how to keep the Opera House maintained, how to pay the bills. Behind the scenes hers was a life of shopping at Wal-Mart and hauling hay for the wild horses, shoveling mud from the theater and mending costumes. But those were the things she did willingly in order to get on with the show.

On stage, the fragile, aging ballerina in a diaphanous white dance costume became the Spirit of Illusion, toe dancing on pointe, transforming herself, transporting her audience into the world of her creation. A world she “couldn’t have created anyplace else,” she said about the Junction.

Becket leaves the Opera House, as well as the rest of the Death Valley Junction property, in the hands of the board of directors of her nonprofit corporation, Amargosa Opera House, Inc. According to General Manager Rhonda Shade, who befriended and took care of Becket during the last few years of her life, the Junction “stays as it is. Everything will continue as she wanted it. Her mission is preserving the art of the past and that’s what we’ll continue to do.”

Shade says that in the last few weeks of her life, Becket seemed peaceful and happy. She had just finished a new painting, and was working with the artists who now perform at the Opera House. Becket died at her home on Monday of a respiratory illness, Shade said. At Becket’s request, her remains were cremated.

A celebration of life is planned at the Opera House for Friday, Feb. 10, exactly 49 years from the day that Becket formally launched her dream. The event begins at 2 p.m. Shade says she hopes to be ready that day to open for visitors a museum that she and Becket were curating together to house some of the many artifacts of Becket’s amazing career.

Shade asked that in lieu of flowers, donations be made to the Amargosa Opera House, Inc. foundation preservation fund.

Inside the Opera House, the floor to ceiling murals still stand, somewhat ravaged by time and the floods and mud that continue to invade the Junction every few years.

Becket leaves a tangible legacy in her paintings, videos of her performances, an Emmy award winning documentary about her life called Amargosa, and her autobiography “To Dance on Sands.”

But where her spirit truly lives on is in the countless artists who were inspired by her determination, by her single-minded will to live her art and her dream.

With serendipitous and Phoenix-like timing, a protégé of Becket’s is debuting her own dance pantomime-inspired show, a circus called El Teatro Grande, in Tecopa on Feb. 11. Jenna McClintock was 6 years old the first time she saw Marta Becket dance and “I was completely transformed forever,” she says.

She became a ballerina, danced with the Oakland ballet, and later, as if drawn like a moth to a flame, ended up in Death Valley Junction dancing on stage under Becket’s watchful eye.

When McClintock left Death Valley Junction last year she moved to Tecopa, where next week, along with her troupe of local artists and inspired by Becket’s lifelong influence, she’ll bring her own dream to life under a big top in the desert.

The indomitable Marta Becket has been liberated from a body that could no longer serve her vision, but her art lives on in Death Valley Junction and in all the ripples of creation that continue to emanate from her epicenter.

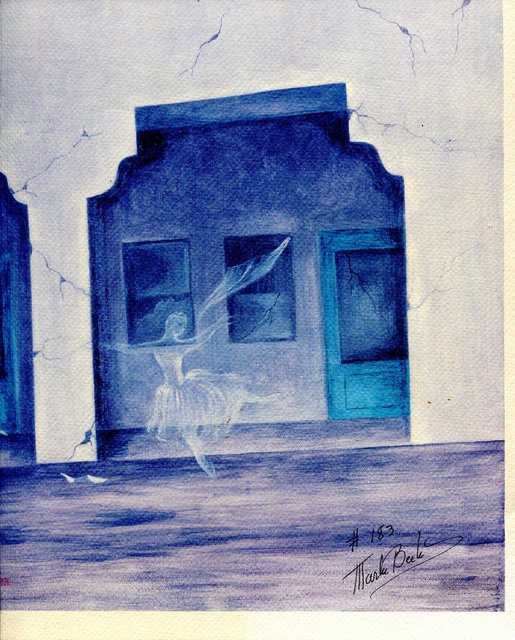

“I won’t last forever, I know,” Becket wrote in 2005. “One day, I too will haunt this place, dancing like a dust devil in the wind.”

Robin Flinchum is a freelance writer and editor living in Tecopa, California. Her book, “Red Light Women of Death Valley,” was published last year.