Captain John Moss was amazing. He was an explorer, mountain man, fur trapper, and prospector for minerals. He found more good mines than anybody I’ve heard of and at times did well financially on his discoveries.

Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, he was a peacemaker and community builder. If we still had a film industry that wanted make quality movies featuring stories that enrich and uplift humanity, one would be hard-pressed to find a better tale to tell.

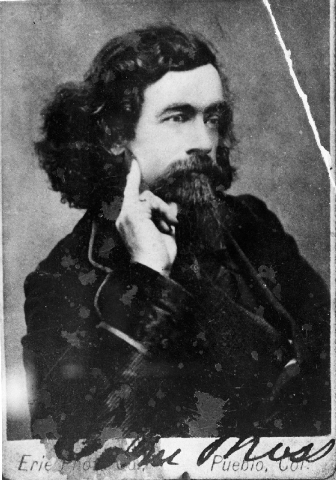

John Moss was a charismatic natural-born communicator. He was about 5’9” tall with broad shoulders and small waist, very athletic and “as lithe as a cat.” He had the good looks of a film star like Brad Pitt.

As one author writing about John Moss put it, he “was evidently well educated, but of an intelligence that would make him learned without it.” Though sometimes referred to as “Captain Moss,” there is no evidence he served in the military. The title was likely used as a term of respect.

John Moss was born in Ithaca, New York, in 1839. As a youth, he moved to Iowa with his family. There he became fascinated with Native Americans, spending time with the Winnebago Indians, learning their language and culture.

He quickly discovered he had a gift for learning languages, which he put to good use over the years in his association with a large number of Native American groups. His ability to communicate with native people, especially in their own language, along with his easy manner and natural appreciation for their way of life, earned him the friendship and respect of many native peoples across the West.

Moss was especially comfortable with the Southern Paiute, Chemehuevi, and Mojave, three closely related tribes in the Southern Nevada-Mojave Desert area, and he enjoyed a special relationship with the Southern Ute in the southern Colorado Rocky Mountains.

John Moss did not long remain in Iowa. He traveled to California in about 1857 and worked as a Pony Express rider. He was a fur trapper and wandered the interior among some 23 tribes of Indians.

At age 22, he showed up at El Dorado Canyon, located on the Colorado River east of present-day Las Vegas. There he is known to have done quite well in the mining game, prospecting, staking out claims, and selling them for a dandy profit. He seldom, if ever, mined, however.

In one deal, he sold a bunch of claims for $5,000, a huge sum of money then. Not long after that, he showed up in the Fort Mojave, Arizona, area, where he was involved in establishing the Mojave townsite and starting a ranch not far from the fort.

A little later, Moss prospected and was much involved at Ivanpah, located at the east end of Clark Mountain south of Las Vegas across the California line. The camp was named for a Southern Paiute term meaning “good water.”

He also did considerable prospecting at the south end of the Spring Mountains in the Yellow Pine mining district, and at the area around Pahrump and Amargosa valleys. Moss Spring in the Newberry Mountains not far north of Laughlin was apparently named for him.

During the Civil War, he was an Indian agent in Arizona. He also prospected in the southern Colorado Rockies, where he was instrumental in establishing a town (Parrot City, now a ghost town) and a county (La Plata); he was the county’s first representative in the Colorado House of Representatives.

John Moss was an adventurer and storyteller par excellence. One early Mojave County pioneer described him as “a hero for a novelist.” Moss claimed to be the first white man to descend the rapids of the Colorado River by raft, doing so alone in 1861. Soldiers constructed his raft, which was 14 feet long and 5 feet wide.

He entered the river near present-day Page, Arizona, and left it near Mohave, Arizona, with the trip taking 3-1/2 days. Once his raft was put into the water, Moss recalled, “It went very pleasantly for a couple of hours, and I rather enjoyed the outset of the boating, but going down more rapidly than I bargained for, and being knocked from side to side, and tumbled about on the raft and drenched by occasional duckings, I did not think it so pleasant.”

In one of his best tales, Moss recounted the time he was prospecting in mountains bordering the Amargosa Valley. He had been two full days without water and didn’t know where he would get his next drink.

At one point, he scanned the horizon and saw a campfire in the distance. Knowing it could be hostile Indians, he judged he had nothing to lose and headed his horse toward the fire.

As he drew close, too late to turn back, Moss realized he had put his life at risk. It was an Indian camp and they seemed ready for combat, apparently not in a good mood. With Moss standing nearby, they held a short confab as to what they should do with this white man.

They could kill him and eat his horse or turn him out on the desert to die. Luckily for Moss, he understood their language well enough to grasp what they were saying.

The confab over, Moss spoke, taking control of the situation. Introducing himself, he said, “I am Narraguinep [the ‘Never Die’]. Have you not heard I cannot be killed? Mountain sheep are better to eat than horse; where are your hunters?” It seems the Indians had been unlucky at hunting recently.

Moss then proposed he go into the hills to hunt, and if they did not hear the report of his rifle by sundown, they should kill his horse and eat it. They agreed.

Moss headed into the mountains on foot. Sure enough, he encountered a small herd of mountain sheep and was able to shoot three before the others escaped. After that, it is said, they nearly worshiped him.

In his years on the desert, John Moss enjoyed great prestige among the tribes of the Southern Nevada and Mojave area. Among many, he was held in a godlike status. And what is most important, he used his prestige for good.

He played the role of peacemaker between whites and local Native Americans almost everywhere he went. There is no doubt his efforts saved many lives.

In more than one instance, he successfully negotiated with local Indians for the right to prospect, locate, and develop mines in specified areas of Indian-held territory. More than once, Indians showed him the location of valuable mineral deposits. Thus, not only was he committed to preventing conflict and bloodshed, he furthered his own prospecting opportunities.

John Moss convinced the Southern Paiute in the Pahrump Valley to take the peaceful path. Moss’s prestige was so great among this group that in the 1860s he played a major role in selecting Chief Tecopa’s predecessor as chief, and later, through succession, Chief Tecopa.

Chief Tecopa venerated John Moss, and when he learned in 1893 that this great man had died years earlier, he sent out word to the Indians in the region and a large ceremony honoring Moss was held at Tecopa’s place on the Pahrump Ranch.

Colonel Thomas W. Brooks, who, like John Moss, was a true man of the West, attended that ceremony in the summer of 1893 and wrote an account of it for the Los Angeles Herald.

Not long ago, I wrote a column on Brooks’s account of that event. We are currently preparing a book that will feature several of Colonel Brooks’s columns on Nye County and southern Nevada from that period, including the one describing Chief Tecopa’s ceremony honoring John Moss.

John Moss died in San Francisco in the spring of 1880, apparently of an old combat wound. He would have been but 41 years old.