Nevada treading water on solving doctor shortage

Nevada’s population continues to balloon, but since 2005 its physician-to-patient ratio has remained “pretty darn flat” despite efforts to attract more doctors to the state.

That’s according to Tabor Griswold of the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine, who also is co-author of a June report that examined the state’s medical provider workforce. It found the number of physicians practicing full time in the state grew just 1.7 percent when adjusted for the population increase from 2005 to 2015.

“The rate of physicians coming into the state was very similar to the rate of the population,” said Griswold, a health services research analyst with the Office of Statewide Initiatives at UNR’s medical school. “So it never improved our rate per 100,000.”

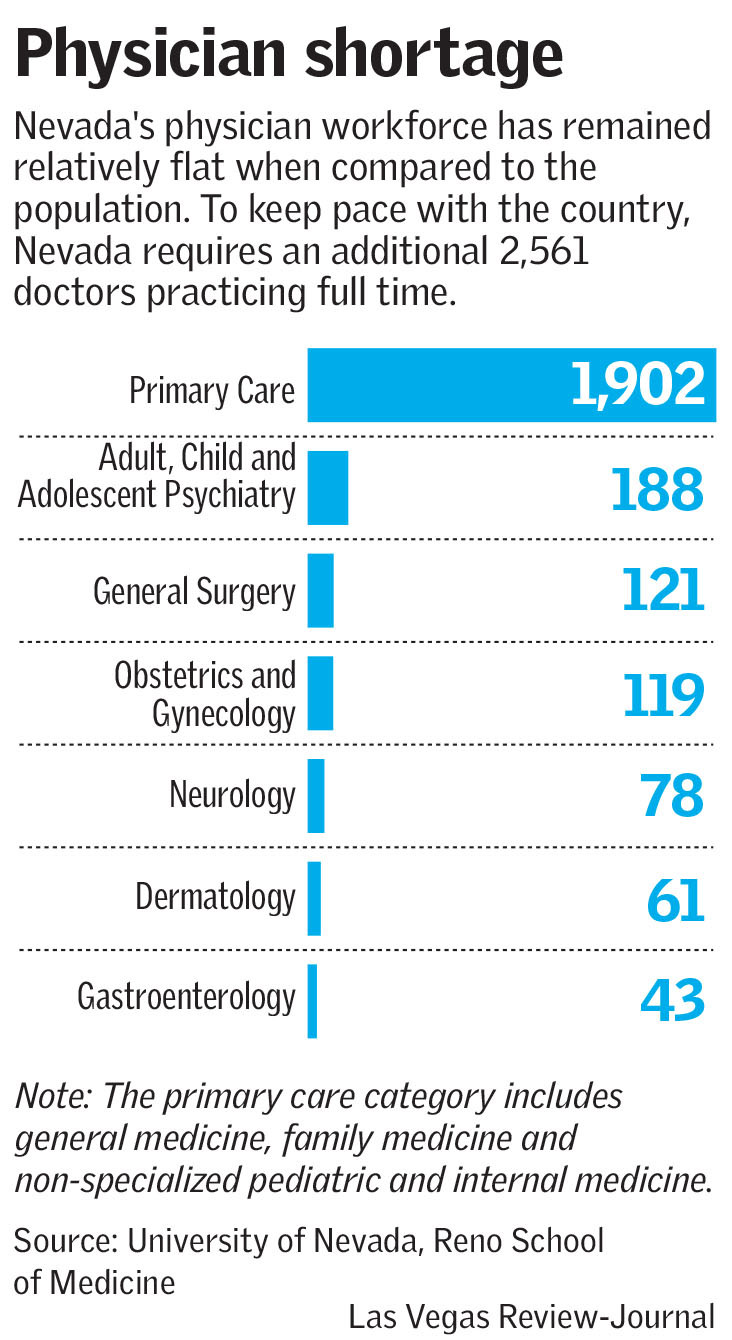

And even if the state’s population remains stagnant — which it won’t — it would take at least 2,561 more physicians just to bring Nevada up to the national average.

In the meantime, Nevada is mired at 47th nationwide for active physicians and 48th for active primary care doctors per 100,000 residents. The report was based on federal data that Griswold said closely matched the state medical board’s numbers.

If Clark County continues to see rapid population growth — it increased almost 25 percent from about 1.69 million in 2005 to more than 2.1 million in 2015 — the doctor shortage could get worse, Griswold warned.

As is, there are just over 180 full-time doctors in Southern Nevada per 100,000 residents, the report said, compared with 303 per 100,000 on average in the U.S.

Republican state Sen. Joe Hardy, a medical doctor and associate dean of clinical education at Touro University Nevada in Henderson, agreed that Southern Nevada has not been able to make significant inroads on its physician shortage.

“We’re bouncing along the bottom,” he said.

More residencies, higher pay needed

Experts say one reason for the shortage is a dearth of graduate medical education — or residency programs — to train doctors after they’ve completed medical school.

“The reality is, it’s not the medical schools where doctors stay,” Hardy said. “It’s where they do their residency.”

The data supports his point. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges’ 2017 State Physician Workforce Data Book, 54 percent of doctors who completed their residencies in Nevada stayed. That was the eighth-highest resident retention rate nationwide.

The state, recognizing that there were more medical school spots in Nevada than residencies, established the Task Force for Graduate Medical Education through an executive order by Gov. Brian Sandoval in 2014 to help determine how funds would be distributed to medical schools and hospitals to support those programs.

The Legislature granted $10 million for fiscal years 2016 and 2017 to fund residencies statewide.

It also authorized creation of a new medical school at UNLV, the third in the state, which opened its doors in 2017.

But other problems persist.

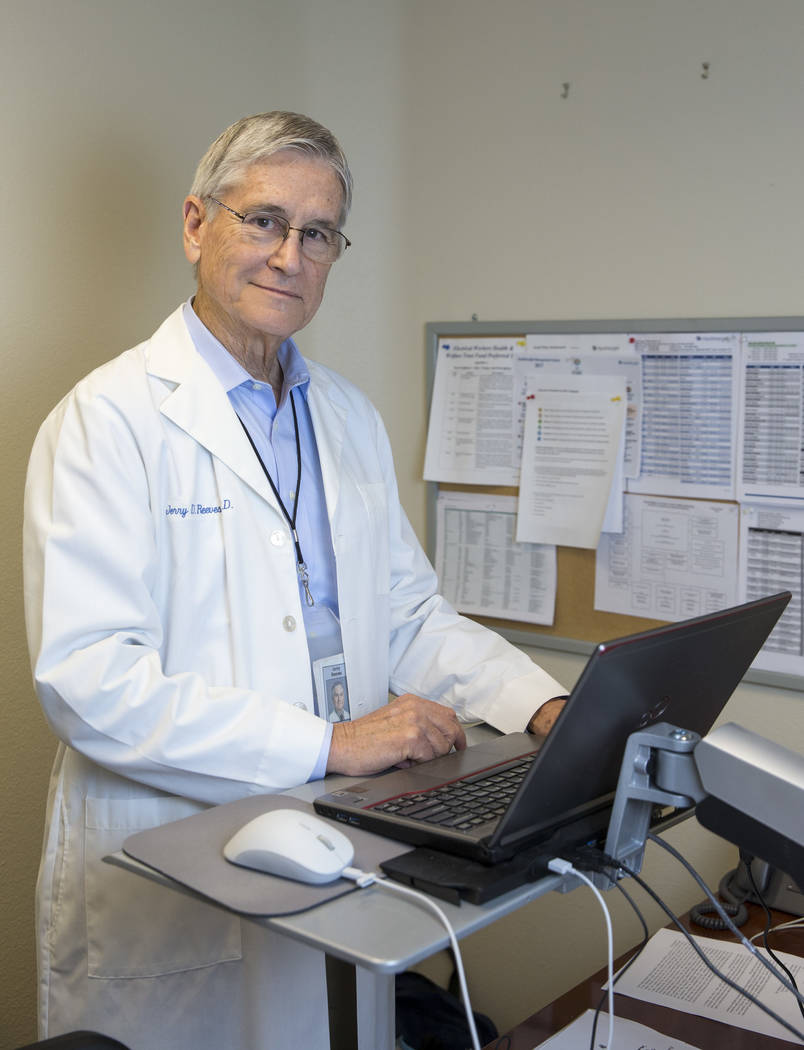

Attracting doctors will take increasing insurance reimbursement, particularly for Medicaid, the public insurance program for low-income and disabled Americans, which often doesn’t cover the actual cost of providing services, said Dr. Jerry Reeves, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist who is the senior vice president of medical affairs for the nonprofit health care consultant HealthInsight.

“It remains very difficult to recruit doctors to Nevada because the compensation rates are not competitive with other states,” Reeves said. “Las Vegas is a very attractive place to live once you’re here … but attracting someone to come here who doesn’t know that yet is tough if the pay isn’t competitive, and there are severe shortages.”

Still, Griswold is hopeful.

“I feel that if a concerted effort is made by all concerned parties of how to develop this graduate medical education piece, the state will make a difference,” she said. Griswold acknowledged, however, that so far “history doesn’t prove that out.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.

At a glance

Highlights of the new Physician Workforce in Nevada report include:

- The total number of licensed physicians in Nevada increased from 5,640 in 2005 to 7,429 in 2015 – an increase of 1,789 physicians or 31.7 percent.

- Over the past decade, the number of physicians in almost every specialty area increased, including primary care, surgery and behavioral health.

- Nevada has a strong record of retaining physicians who are educated and trained in the state. For example, in 2017, 76.7 percent of physicians who completed both undergraduate medical education, and graduate medical education in state, are currently practicing in Nevada (ranked No. 9 among U.S. states).

Source: University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine