Awhile back, Tonopah community leader Bob Perchetti suggested I write a column about my father, Robert G. McCracken, also known as Bob.

He was especially interested in my dad’s career as a professional wrestler. Since this month is the 60th anniversary of my family’s arrival in Nye County, I thought now might be a good time to do it.

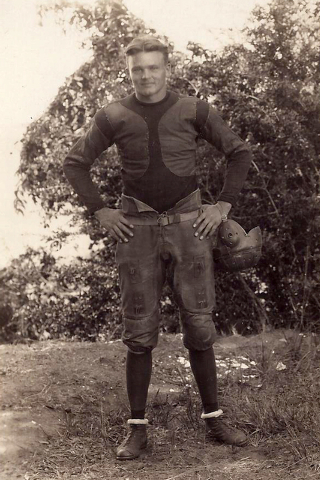

My dad was born in Kansas in 1905 and grew up there. He attended St. John’s Military School in Salina, where he developed an interest in wrestling and football. Upon graduation, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. While in the Marines, he served as a drill instructor at Paris Island, South Carolina.

In those days, if a recruit didn’t approve of the way his drill instructor was handling things, he could challenge him to fisticuffs at the end of the day. Those who challenged my dad always came to regret such a confrontation.

While in the Marine Corps, he played first on the Paris Island football team and then on the all-Marine team at Quantico, Virginia. In those days, the Quantico team played the top colleges.

Somewhere along the way, my father caught gold fever — the deeply held desire to look for gold — with the idea that it was more than just possible to hit the big strike.

Unfortunately, as Bobby Revert in Beatty, who knows a great deal about the mining game, wisely points out, “Gold fever is almost always a prescription for poverty.”

Many are called but few are chosen. My father got out of the Marine Corps about the time the Great Depression began in 1929. He ended up digging for gold in the hills above Boulder, Colorado, working with old-timers who had earlier looked for riches in such legendary places as early Tonopah and Goldfield. They taught him how to mine and filled him with tales of the big strikes a man could make if he worked hard and had a bit of luck.

In order to pick up extra cash while living in the mountains above Boulder, he and a good friend from his Marine Corps days, Fred Kimball, put on wrestling exhibitions in eastern Colorado and western Kansas. I think they even ended up wrestling in New England a few times.

In these matches, Dad always played the good guy and Fred the villain. Dad was a good wrestler, but Fred was world class. He had a portfolio of wrestling maneuvers and could, if he wanted, almost instantly cripple any opponent in a serious confrontation. For example, he was the world expert in one wrestling hold that, within seconds, would enable him to disable any opponent by breaking his arm at the shoulder.

Both Fred and my dad had thick cauliflower ears, a sure giveaway that you were in the presence of highly experienced fighters, until the day they died. In those Colorado and Kansas matches during the Depression, often there was some big hayseed in the audience yelling “Fake! Fake!” — which, of course, it was. On such occasions, after the match, Fred would announce, “If you think it’s a fake, come up here and I’ll break your arm.”

Every now and then, some local tough guy would be dumb enough to take the challenge and Fred would break his arm. From the mountains above Boulder, my dad’s quest for the big strike took him to the Cripple Creek/Victor District in Colorado, where he used to say he missed a large, rich vein of gold by mere inches.

From Victor, his quest took him to the old gold camp of Breckenridge, also in Colorado, then to New Mexico. In 1952 he took a steady job in Ely helping sink a big incline shaft for Kennecott Copper. While in Ely, he got interested in an old mine located in the Reveille Mining District in the Reveille Range, 60 miles east of Tonopah in Nye County. In 1954, he purchased an interest in that mine.

Ore was first discovered in the Reveille Mining District in 1866 and the town of Reveille quickly sprang to life.

It soon had 150 inhabitants and a post office and two stores. Some 950 mining claims were located in the district. Due to lack of water locally, a five-stamp mill was constructed 12 miles to the west in Reveille Valley in 1869 and in 1875 it was expanded to 10 stamps, producing about $1.5 million in bullion. Ore from the district ran from $75 to $100 per ton in lead and silver, with high-grade running as high as $1,500 per ton. The district folded in 1880 and there were sporadic efforts at reviving mining there over the next 70 years.

REVEILLE MINE ADVENTURE

In June 1954 my father took on the challenge of developing what we called the Old Reveille Lead and Silver Mine, thinking it was his chance for the big one.

He refurbished a one-room shack at the old mill site in Reveille Valley. With help from me and my brother, Mike, we made a few repairs on the old mill there, which consisted of a 30-ton ore bin, a bucket elevator to feed ore into a ball mill with a two-ton-per-hour grinding capacity, and a shaking table to concentrate the lead and silver values in the ground-up ore.

A full ore bin would yield, as I recall, two or three 55-gallon barrels of ore concentrates that ran over 50 percent lead and 150 ounces of silver per ton, with lead at around 15 cents a pound and silver under a dollar or so. We obtained our ore by hand-screening the old dumps at the mine itself, located above the valley on the west side of the Reveille Range.

My dad and three teenaged boys — me, my brother, and the son of an investor in the operation from California — could obtain about five tons of screenings per day, which we hauled across the valley to the mill at day’s end in an old dump truck. Six days of screenings yielded a full ore bin.

Once a week, we drove the truck into Tonopah for supplies. We got our mail at Warm Springs. The Terrell brothers, Solan, Bud, and Starl, were operating their mine at Eden Creek high up in the Kawich Range at the time and always stopped to visit when they passed through our camp, as did the Fallini Brothers, Joe, Bill, and Ray, and their families, who ran cattle in the area from their ranch’s headquarters at Twin Springs.

Nearly all travelers up and down Reveille Valley would stop and visit at that time. And, isolated as we were, we were always glad to see my dad’s efforts at Reveille went on for several years. The mill was expanded and a hoist installed at the mine shaft, enabling us to hoist previously broken ore from the mine for milling. Participants in the deal came and went.

At one point, a very skilled promoter from South Dakota got involved and raised a considerable amount of money for the operation. Early on, he asked my brother and me what kind of new car we would buy with all the money we were going to get.

I said, “A new Thunderbird.” My brother said, “A new Corvette.” The promoter replied, “Why not a Studebaker Golden Hawk? They’re great.”

We said, “No, we’ll take the bird and ‘vette.”

“Okay, it’s your choice.”

Over a period of a couple of years, our promoter raised several hundred thousand dollars intended for my dad and the mine, but we saw very little of it. He provided just enough cash to string my dad along. It turned out, the promoter gambled away much of the money he raised. My dad believed that the Reveille Mine and mill had rich potential. The potential was there, but reality made it impossible to fulfill the dream. During this period, we made a small effort to develop a mine at Silver Bow at the south end of the Kawich Range, and another at Bellehelen, also in the Kawich.

CHASING RAINBOWS

Meanwhile, I had finished high school and was attending college at the University of Colorado, with summers spent mining.

In 1959, Dad turned his attention to the mine at Bellehelen, which looked like a good opportunity. In late September 1959, I had just enrolled in my third year at the university. For some reason, I went to a gypsy fortune teller. She told me, “Your father is starting a new venture. He needs you. He loves you very much. If you go with him, you will get rich.”

That was all I needed to hear. I decided to withdraw from school and go help my father. In order to withdraw from the university, I had to have a high official sign my withdrawal form. When I met with her, she looked over my form and me and asked why I was leaving. I told her about my dad’s new mine and what the fortune teller had said. How wise she was. She could see it all.

She asked me, “Are you sure you’re not chasing a rainbow?”

After our efforts at Bellehelen in the Kawich Range did not yield the hoped-for riches, I returned to the university and stayed there for the next seven years, returning to Nevada most summers.

When I needed money to continue my studies, thanks in no small measure to Bill Beko and Toni Buffum, I was able to get summer jobs at or near the Nevada Test Site through the labor union. My dad’s experience as a hard-rock miner was put to good use at the Nevada Test Site, where he worked for more than 20 years before retiring to his cabin in Tonopah. He died in 1994 and is buried in the Tonopah Cemetery.

Like so many men and women of our great West, my dad was a chaser of rainbows. I suppose you could say I have chased my own rainbows — love of research and writing, history, science. What are we, after all, without our rainbows?