Republicans received decisive defeats in Virginia, New Jersey and local elections elsewhere on Nov. 7.

Voters sent a clear message of disapproval to President Donald Trump, with Democrats enthusing that their victories are a harbinger for 2018.

However, Democrats risk overplaying a good hand. The new Governor-elect of New Jersey, Phil Murphy, a former Goldman Sachs millionaire, is an all-out “progressive” who wants to raise the Garden State minimum wage to $15.

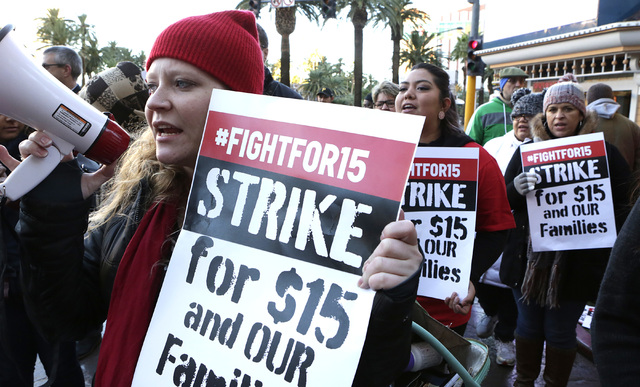

The “Fight for $15” is a popular “progressive” rallying cry. The notion of raising the minimum wage appeals directly to concerns about income inequality and it’s a simple enough concept to fit neatly on a bumper sticker.

There is just one major problem. Minimum wage increases don’t translate into big income increases for low-skill workers when taken to extremes.

The “Fight for $15” is largely funded by the Service Employees International Union that has spent more than $90 million on the campaign since its launch in 2012. With membership declining, the SEIU has tried to unionize restaurant workers, with little success so far.

In recent years, the popular idea of a $15 minimum wage translated into electoral and legislative victories. San Francisco, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh and Washington are among the cities where a $15 minimum goes into effect in coming years. California has a statewide law being phased in.

But cautions are already looming. In Seattle, where a phased-in $15 an hour wage was adopted in 2014, a University of Washington study found that employers have already cut back on hours to compensate for the higher wages. The study established that the second round of wage boosts to $13 an hour produced a 3 percent increase in average wages, but employers cut back 9 percent on hours, meaning that workers suffered a 6 percent drop in total wages paid.

Similarly, a Harvard Business School study of San Francisco’s ever-rising minimum wage—set to hit $15 next year—found a 4-10 percent increase in restaurant closures for every dollar of wage increase.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported that restaurant prices had jumped 52 percent since 2005, twice the rate of inflation.

Andrew Puzder, Trump’s first nominee for Labor Secretary and former CEO of CKE Restaurants (Carl’s Jr. and Hardee’s), observed that when the minimum wage goes to $15 “you kill jobs” and encourage automation. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that raising the minimum wage to a mere $10.10 per hour would result in a job loss of 500,000.

The $15 minimum wage doesn’t match reality.

In March, Baltimore’s newly elected mayor, Democrat Catherine Pugh, vetoed a measure that would have raised the local mandate to $15 by 2022. “Í want people to earn better wages, but I also want my city to survive,” Mayor Pugh said. Lawmakers in several other states are also pushing back against local minimum wage increases.

Nevada’s state minimum wage is currently $7.25 per hour for those with health insurance benefits and $8.25 without insurance. That closely tracks the federal minimum wage of $7.25. Nevada is among 18 states indexing the minimum wage to inflation.

In the 2017 Legislature, SB 106 was passed on party-line votes in both the Senate and Assembly. The bill would have incrementally raised the minimum wage by 75 cents annually, reaching $11 an hour with insurance and $12 an hour for those without it, in 2022.

Nevada Gov. Brian Sandoval vetoed SB 106 citing negative consequences of job losses and higher costs for goods and services. A statewide minimum wage in Nevada is complicated by the fact that labor costs are radically different in Las Vegas when compared to Nevada’s rural communities.

States and cities across the country will need to slow down and carefully examine the full effects before pushing ahead with a $15 minimum wage. It may fit on a bumper sticker—but that doesn’t make it a good idea.

Jim Hartman is an attorney residing in Genoa, Nevada.