Nevada mining family strikes turquoise on reality TV show

Editor’s note: This story follows up on one from the Aug. 7 Pahrump Valley Times. A link to that news story is available on the internet at bit.ly/2OSAm2Z

Even if he had attempted to hide his tears, the dust on his face would have betrayed their passage. Tony Otteson is at once rattled and relieved, a brief show of emotion cleansing the desert dirt from his sun-ripened cheeks.

He thought he almost lost him just now, his brother-in-law, T.J.

It all happened in a flash.

The two were on the job with Otteson’s brother Trenton. T.J. was manning an excavator over a ridge while Tony and Trenton were doing what they do, what they’ve always done: mining for turquoise.

But then one of the excavator’s treads shot off — just like that, as quickly and unexpectedly as a sudden muscle spasm — the machine tumbling perilously to its side. T.J. is instantly in danger of being crushed.

Like sand steadily, deliberately making its way through an hourglass, there gravity was, demanding its due with each passing second.

T.J. smashes through the excavator’s glass windshield as if his life depends on it. It does.

“I’m shocked that I’m here right now,” he confesses afterward, and you can almost feel his rubber legs as if they were your own.

“I just thought I was done,” he adds plainly. “I knew I was going to end up underneath it somehow.”

Instead, he deprives the Ottesons’ Widowmaker mine of the opportunity to live up to its name, at least on this day.

“We’re not making cotton candy out here,” Tony says, dabbing moisture away from his eyes. “This is dangerous.”

The scene is captured in dramatic detail in the debut episode of the reality-TV series “Turquoise Fever,” which is set in the wilds of rural Tonopah. It premiered at Aug. 14 on the Western-leaning INSP Network.

Think of it as a family-centric, terrestrial version of “Deadliest Catch,” with the Ottesons’ 65 claims on 43 mines in place of various fishing vessels, turquoise subbing for snow crabs. As with that Discovery Channel hit, the stakes here are as high as the mountain peaks the Ottesons have worked for three generations, ever since Tony and Trenton’s grandpa Lynn Otteson moved to Tonopah to mine Royston turquoise in 1958.

Out here, it’s 70 miles to the nearest hospital.

Cellphone reception? You might as well be dialing from the bottom of the ocean.

If you get hurt in these conditions, your luck quickly turns as hard as the rock formations being excavated. And really, it’s not a matter of if but when.

“Every day, there’s a great opportunity to smash your hand with a hammer hard enough to blow the meat out of your thumb, or take a rock to the head that could change your life forever, or be crushed by an excavator bucket, or get blown up,” Tony Otteson says. “That’s every day.”

Why do they do it, then? Because turquoise is far more valuable than you might think, with the best of the best commanding $1,000 a carat. That’s a million dollars a pound.

But that’s not really why any of the Ottesons bruise their bodies, head to toe, daily, boring into the earth with a near-religious devotion.

“You could take all the money I make from digging turquoise away. Same for every other Otteson family member, and you’ll still find us out there in the dirt, still digging rock,” Tony says. “It’s a true fever. There’s no getting rid of it. You could watch your house go under, lose your car, lose your truck, we’ll all be riding horses. Come and take our horses, we’ll walk. Take our shoes, we’ll crawl. We’re still going to go out there. It’s what we do.”

His brother puts it more succinctly.

“It’s in our blood, man,” Trenton says. “We bleed blue.”

The hills have eyes and riches

They call it blue gold, though nowadays it’s gold that should be blue: Turquoise is often worth more, believe it or not.

Plenty don’t.

Can’t blame them, really. When it comes to the gemstone in question, reputation and reality often diverge.

“Like most people, I probably thought of turquoise as a cheaper gemstone that was sold in tourist traps,” says Craig Miller, vice president of original programming at INSP Network, who green-lighted “Turquoise Fever.” “I came to realize that that’s not the case at all. There is junk turquoise, but there are different grades of it, and the highest-grade stuff is extremely valuable. Most Americans don’t think of it as a high-end gemstone, but if you look at the history of it, it has been.”

Turquoise is currently more valuable than ever, capable of fetching hundreds of thousands dollars a pound — and even more for the truly premium specimens. A big reason is basic scarcity: It’s a nonrenewable resource, formed over millions of years when water seeps through rocks containing copper, aluminum and other minerals, as “Turquoise Fever” details. The water gradually accumulates color and hardens. The bluer it is, the more copper-rich it has become; greener color means more iron is present.

Turquoise’s idiosyncrasies enhance its worth. No two pieces are alike, just as no two mines produce the same type of gemstones. Turquoise from the Ottesons’ Montezuma mine, for instance, is known for its dark blue-green color and golden-brown matrix; the Widowmaker’s spoils tend to be a deep shade of blue.

Regardless of type, turquoise supplies have become more limited with each passing year, heightened by recent shifts in the domestic mining industry.

“For many, many years, 90 percent of the turquoise market in the U.S. market came from Arizona,” explains Donna Otteson, the family matriarch, who runs her own jewelry business. “It was actually a byproduct of the copper mines. They were extracting huge amounts of material. Well, those copper mines have now been shut down, and those resources are no longer available. For us, it increases the value of our turquoise.”

But first, there’s that whole thing of getting the stuff out of the ground.

A hard-earned turning point

He remembers the blood on their hands, the dirt on their clothes, the look in their eyes: fatigue mingled with resolve, a hunger for food and fortune alike. Tony Otteson was around 5 years old at the time. He and his siblings often would accompany their elders to the mines, hunting lizards while the men worked.

All these years later, he recalls the looks on their faces as if he was looking into a mirror. And in a roundabout way, he is.

“Watching them come out of the mines at the end of the day, they were beat up, like, every day. They didn’t leave the mines until they looked defeated; they could barely walk,” he says. “I grew up with that work mentality: ‘That’s what a man does. That’s what life’s supposed to be like.’ ”

It wasn’t an easy life. Especially back then. Long before there were reality-TV shows, there were hard times upon still harder times.

“I remember sitting down as a family and sifting weevils out of wheat flour, because for a couple of months anyway, our major food supply was a sack of wheat flour that the church had donated to us,” Tony recollects. “We were sifting weevils out of it so that we could make pancakes. If I never see a wheat flour pancake in my life again, that would be too soon. The money would be so scarce at times that a deer from the mountains, that really was dinner. It was what we could get.”

It was enough to make Tony question whether he truly wanted to join the family business when he came of age.

“I grew up thinking, ‘I want to be a little bit different. I would like to have a real job and steady income,’ ” he acknowledges. “But in the words of my cousin Tristan, as an Otteson, I don’t care how far away you get from the turquoise mines, what kind of schooling you go to, what kind of business you’re going to create. These turquoise mines will always pull at your heartstrings.”

That tug proved to be too hard to resist for Tony and Trenton. And their combined efforts, along with those of the rest of Otteson clan, would eventually pay off to an increasingly profitable degree. A turning point came in 2002 when they discovered some high-grade turquoise in the Candelaria Hills. Trenton took it to market, and a potential buyer offered $20,000.

He knew in his gut that it was worth more. He passed.

“A lot of family members were not happy that I turned that down,” he recalls. That disappointment, though, would soon shift directions as swiftly as the desert winds. The turquoise sold for $80,000.

“I learned where all these new buyers from Japan were, all the real high-priced buyers,” Trenton recalls. “I did lose one sale, but I gained about 50 new sales.”

With the proceeds, the Ottesons reinvested in their business, going from owning a single backhoe purchased for $4,000 and having an engine that didn’t work at the time, to multiple excavators, a dozer and more, allowing them to do heavier, more lucrative mining.

All those wheat flour pancakes were a thing of the past.

As far as tricky things go, blowing holes in mountains deserves a mention.

You have to learn how to read the ground. That’s the key. But sometimes there’s more to it than meets the eye. And all you have is your eyes. This is the hard part.

Think of trying to read a putting green before taking your shot, of the difficulty of discerning just what path the ball might travel and how any little detail unaccounted for could alter that path. Then, add explosives.

If you’re wrong in this context, you don’t just add a stroke to your golf game. You could cost yourself and your family thousands of dollars in ruined turquoise. Finding the stuff, that’s only half the challenge — maybe the easier half, even.

“You take all this time and money to locate turquoise and find where it’s coming out of the ground. That’s just the beginning,” Trenton says. “Then you got to figure out what kind of ground it’s laying in because you’ve got really hard rock, like quartzite-type rock, and then in between that, you’ve got clay. Then you’ll have another layer of hard quartzite rock and maybe some sandy material.

“You’ve got to figure out how to drill that, shoot it and understand the shock wave from the dynamite,” he continues. “You’re trying to get the biggest chunks of glasslike material out of there. A shock wave, when it comes through glass, it’s just going to fracture it into a million pieces. You have to be extremely careful not to blast the turquoise.”

Blasting 50 tons of rock from a mountainside then, which we see the Ottesons do during the second episode of “Turquoise Fever,” is a more nuanced process than one might think, requiring strategically placed, 18-foot-deep drill holes that get filled with dynamite and 150 pounds of ammonium nitrate — enough to vaporize a car — to fuel the blast.

It’s a mentally and physically demanding task, the latter exacerbated by the punishingly harsh landscape. Most of the mines are 7,000 feet above sea level, and in some instances, like the Blue Moon mine, it’s all black dirt and black rock simmering beneath the sun.

“I think the biggest danger that we have for these guys is exposure,” Donna Otteson says.

Tony Otteson has experienced the effects of this exposure to a brutal degree. He had skin cancer removed from his eyelid two years ago and has a sister who’s getting it cut out of her ears. He recalls a particularly grueling mining expedition during which the heat became suffocating.

“You’re way past feeling like you’re hot,” he says. “You don’t feel good inside. You’re starting to speak slowly, saying weird things. You get up to go walk, and you realize you just stood up and didn’t take any steps and just fell over, but your brain says you were walking. I’m like, man, there’s something wrong.”

A thermometer fetched from their travel trailer read 134 degrees.

‘Almost like a drunken feeling’

The tears are different this time.

Donna Otteson’s emotions are as plain to see as the gemstones that have just been unearthed. It’s a bittersweet scene. The family has made a major turquoise find at its once-dormant Blue Moon mine, which they reopen in the second episode. Only her husband, Dean, isn’t here to join in the moment.

“This was Dean’s dream,” she says, choking up a bit.

During the filming of “Turquoise Fever,” Dean died of cancer.

One of the main early storylines of “Turquoise Fever” sees the family rallying around Donna, attempting to help relaunch her jewelry business after Dean’s death. To do so, she needs turquoise — and plenty of it. And so they revisit Blue Moon, eventually leading to a breakthrough haul that enables Donna to get back at it.

Watching the family come together to celebrate the score is to see turquoise fever at its most contagious.

“When we finally get into some turquoise out there in the rough, you’ll see these nuggets, and the hair will stand up on your arms,” Trenton says. “It’s almost like a drunken feeling.”

To hear his brother tell it, the feeling is such a hard-earned one that it heightens the intoxicating surge Trenton speaks of.

“When you’re down in the hole and you’re swinging a hammer, swinging a hammer day after day and finally behind that last rock, boom, there it lays. It’s a true feeling of like …” Tony says, voice trailing off as he attempts to describe an indescribable feeling. “All the work that you just put in, the broken fingernails, the bloody knuckles, missing your kids, your wife’s crying that you’re gone. It’s just, like, vindication.”

Not just for himself. For all the Ottesons.

“We have a saying in my family,” Tony says. “It goes like this: ‘We work in the land that nobody knows. And we live in a land where the wind always blows. But we strive in a place where nothing grows. Because the earth lays treasures under our toes.’

“We always will find those treasures,” he adds. “That’s what we do.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.

At a glance

Turquoise Fever follows the Ottesons as they battle blistering days and freezing nights, detonate explosives on treacherous slopes, and struggle to pull enough of the sought-after stone from the desert to keep their business going for a fourth generation.

Turquoise Fever is comprised of six episodes. The concept was created by Silent Crow Arts, and the pilot episode was produced by Essential Media. The series is being produced by Glassman Media.

Source: INSP

A closer look

To watch a promo video for Turquoise Fever go to bit.ly/2FG2Eqn on the web.

About INSP

INSP is available nationwide to more than 78 million households via Dish Network (channel 259), DirecTV (channel 364), Verizon FiOS (channel 286), AT&T U-verse (channel 564) and more than 2,800 cable systems.

For more channel information, go to insp.com/insp-channel-finder

Source: INSP

How 'Turquoise Fever' came to be

It was that age-old story of one Western-themed mining reality show begetting another.

About five years ago, Tony Otteson was digging into an episode of the Weather Channel's "Prospectors," its titular mineral hunters largely working the Rocky Mountains.

"I loved it," he recalls. "But I thought, 'Man, they're missing out on a lot, because these prospectors are mostly in Colorado and they're just digging up crystals. Nobody knows how we get turquoise out.' "

So he set out to change that, contacting the company behind the show to see if it was interested in doing something similar with his family.

"They liked it right away," Tony says. "The problem was they had so many characters on that show already. They were like, 'We only need one or two of you because we already have a big family on 'Prospectors.' '' We knew right away that with one or two of us, it just wasn't going to work. It takes a village full of Ottesons to get done what we're doing."

So they passed. But word quickly spread to other production companies.

The Ottesons started fielding calls, one of which was from producer-director Matthew Bennett of Silent Crow Arts, the team behind "Deadliest Catch" after-show "Deadliest Catch: Revelations," among others.

"He was like, 'You guys have lightning in a bottle here,' " Tony recalls. " 'Let's run with this.' "

And "Turquoise Fever" was born.

It took a few years to get the project off the ground, but it eventually was picked up by the INSP Network, whose programming consists largely of classic Westerns.

Craig Miller, vice president of original programming at INSP, believed that the Ottesons would fit right in with their saddle-and-spurs demographic.

"While this is not a straightforward cowboy show, if you've met the Ottesons in person, they're cowboys," he explains. "When they're not mining for turquoise, you're going to find them in cowboy hats and cowboy boots. They're modern-day cowboys. They just happen to make a living digging turquoise instead of raising cattle."

Throughout the filming, the Ottesons had one overriding demand: "We really wanted it to be real," Donna Otteson says. "We didn't want them to put words in our mouth. We didn't want them telling us how to do our jobs."

Miller chuckles at the thought of the Ottesons being anything other than themselves.

"They're not actors," he says. "They're turquoise miners. What you see is what you get."

Meet the Otteson family

Donna

The family matriarch. Her husband, Dean Otteson, died of cancer during the making of "Fever." She also runs her own jewelry business.

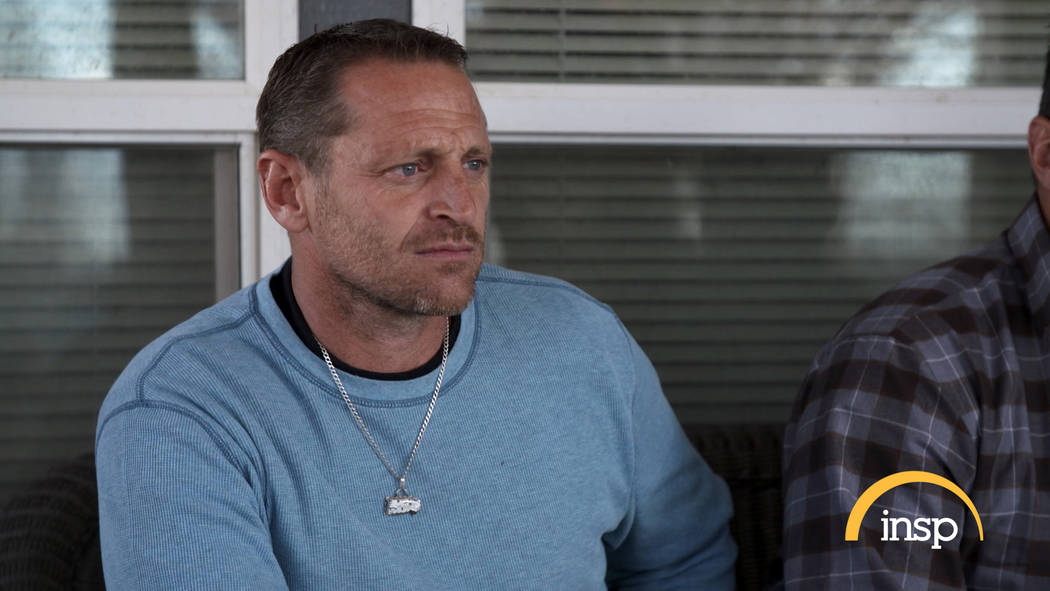

Tony

One of Tommy Otteson's 10 children. He now lives in Phoenix and makes the 11-hour drive to the Otteson mines every few weeks.

Trenton

Tony's brother, who has a home in Las Vegas.

Danny

A second-generation miner who learned the ropes from his late father, Lynn Otteson.

Tommy

Danny's brother, an expert stonecutter.

Tristan

A third-generation miner, Danny's youngest son.

Lane

Tristan's older brother. The two also operate their own claim.

Emily

Tony's wife, who helps manage online sales and social media accounts.

JaKell

Trenton's wife, who works with Emily in marketing the family business.