Leilani Thorpe has always been concerned about cancer, as three of her family members have died from the disease.

But after her mother died from stomach cancer in 2017, she was in shock.

Thorpe, who lives in the small town of Owyhee on the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation, knows many fellow residents who had family members die of cancer since the 1970s.

“For such a small community we have had so many people who have died from cancer,” Thorpe said.

In fact, more than 100 members of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation, located on the Nevada-Idaho border, have died over the years due to cancer, said Chairman Brian Mason.

For a tribe of about 3,000 members, that is a large number, he said.

After talking with residents and tribal members, he learned there was one thing they had in common: they all attended the same school on the reservation.

The 70-year-old Owyhee Combined School, where tribal members have been educated for generations, sits adjacent to hydrocarbon plumes that lie underneath the town, Mason said. He thinks the school, where drinking water was once contaminated by the plumes, is the root of the problem.

“We have to get a new school,” Mason said.

The Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation, which operates under one unified tribal government, is looking for legislators to carry a bill in the upcoming legislative session proposing one-time funding for $77 million to build a new school in a different location.

Thorpe, who graduated from the school in 2001 and has four children attending the school, worries about the health and welfare of her family and the tribal members.

“This is my home,” Thorpe said. “I’m not living anywhere else. I would have to if they ended up shutting down the school, of course.”

Contaminated

Owyhee is tucked in a valley surrounded by mountains and canyons, with a river that runs north. About 2,000 tribal members live on the reservation and around Owyhee, which some interpret to mean “yellow knife,” as well as some ranching families, health care workers and teachers. It is one of the most isolated communities in the continental U.S. and is more than 90 miles in any direction from the nearest interstate, said Lynn Manning John, vice principal of the Owyhee Combined School and member of the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation.

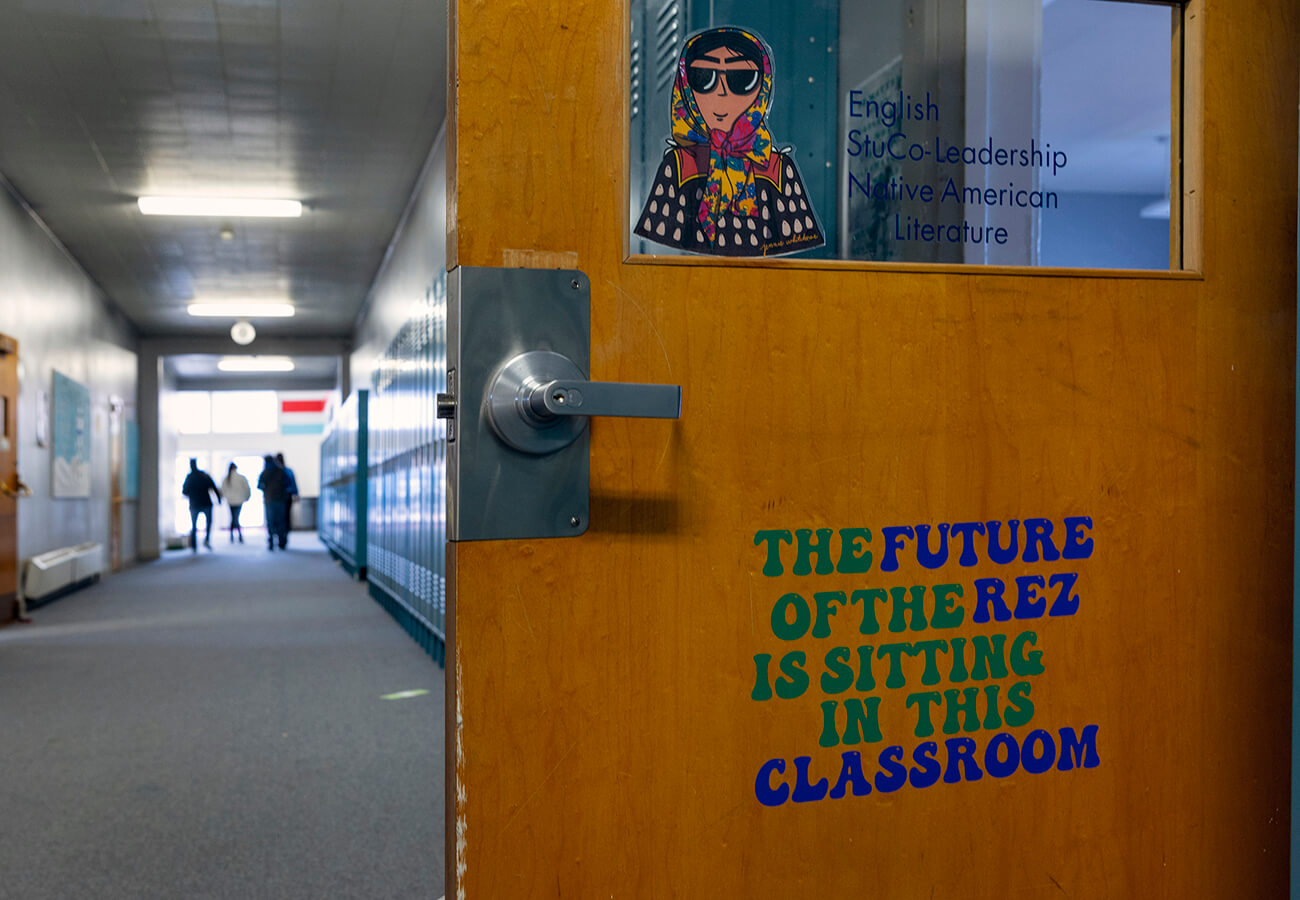

The Owyhee Combined School, a one-story building built in 1953 in an art-deco style, has well-lit rooms, large windows, and beautiful architecture with a stone fireplace and entrance, Manning John said. The school’s sports teams do well, and the students are phenomenal.

“We are very proud of our school as far as our kids that come out of there,” Manning John said. “But not every kid is going to feel great enough coming out of that school. If kids don’t feel good about the building, they’re not going to show up. And if they don’t show up, they can’t achieve.”

Manning John said it is difficult to speak poorly about her school and her building, because inside it is the future of her tribe: her students.

“They are the next chairperson, the next councilperson, the next teacher,” she said.

Up until 1993, the Bureau of Indian Affairs ran the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation before the tribe secured self-governance, Mason said. Beginning in the 1950s, the bureau owned a maintenance shop on the reservation in which diesel and other oils and waste were disposed of through a shallow injection well.

In the 1980s, the school’s water began tasting and smelling like fuel, Mason said.

The Environmental Protection Agency conducted an inspection of the maintenance facility in 1994 and found a “sludge-like substance” in the floor drain, according to a court order from the agency. Samples taken indicated that contaminants may have been disposed of “in a manner that may have endangered the health of persons or risked causing exceedances of primary drinking water regulations.”

EPA finding by Steve Sebelius on Scribd

The EPA found that the Bureau of Indian Affairs did not have procedures in place for disposing of waste products containing petroleum hydrocarbons, “other than disposing of these materials into the disposal well or onto the ground surrounding the maintenance building,” the court document says.

Multiple public water supply pump houses were located within about 100 feet of the facility, the EPA found, and in 1985 two wells were taken offline due to petroleum hydrocarbon contamination, according to the court record. Another public water supply well located 250 feet northeast of the pumphouse “continues to provide drinking water to the community,” the court report says.

“Contaminants are present in or likely to enter the (drinking water) and may present an imminent and substantial endangerment to the health of persons,” the court document said. In the court document, the EPA ordered the Bureau of Indian Affairs to stop injecting fluids into the disposal well and to come up with a plan for mediation.

The Owyhee wells that the school and the town used were capped off and abandoned, and they were replaced with new wells north and south of the town in 1992.

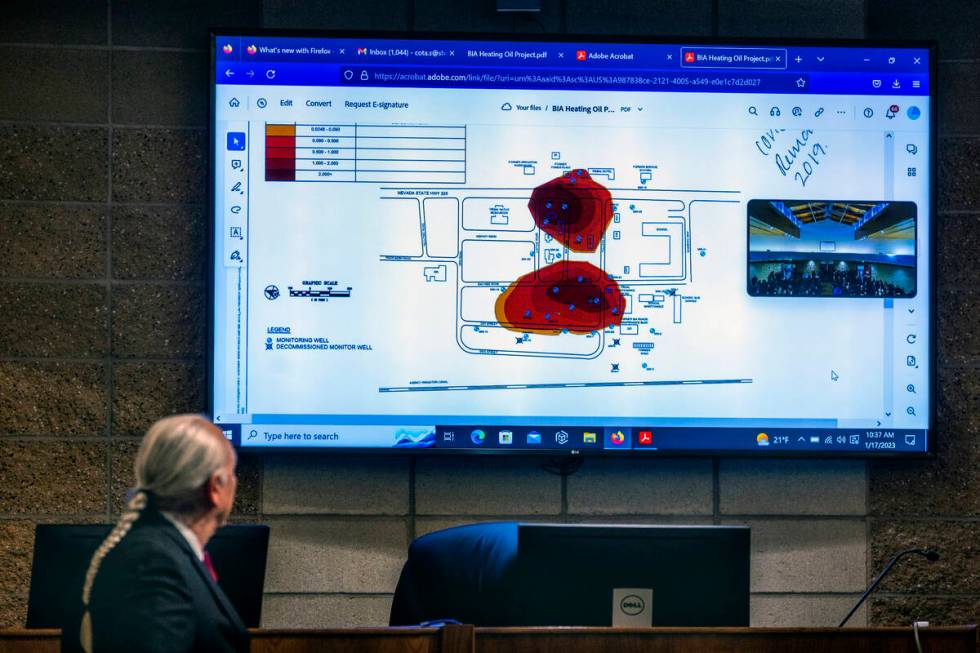

Besides the maintenance building contributing contaminants in the 1970s and 1980s, about 8,000 gallons of heating oil were released from subsurface piping in 1985, according to a January 2022 presentation from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Four hydrocarbon plumes underneath the town were discovered, each containing different contaminants, including gas, diesel, heating oil and pesticides, which the agricultural community had used to spray on its wheat, Mason said. Those plumes underneath the town, while no longer connected to the tribe’s drinking source, is still active. Samples taken in 2019 show concentrations of diesel, gasoline and naphthalene, which is made from crude oil or coal tar and used as a pesticide, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which briefed the tribe on the state of the plumes last year.

Damage done

Though the wells were capped off and replaced with new ones, years had gone by with students and staff drinking the water from the school. Many of the lunch ladies who worked at the school had died from cancer, and students who had gone to the school in the 1960s and 1970s have died as well. Mason does not know the exact number of people in the community who have died as a result of the contamination. The tribe was going to conduct a medical survey with its members, but he did not want to create a panic, Mason said.

Many tribal members were not aware of the plumes underneath the town and the EPA’s reports until recently.

“It’s kind of upsetting how not a lot of people knew,” said Yvette Thacker, a tribal member whose five children attend the school.

Wilma Blossom, a tribal member who will soon turn 82, said her husband died about two years ago from lung cancer. He had worked at the Bureau of Indian Affairs and had been part of the clean-up crew after the contaminants were discovered. Other family members of hers had died from cancer, and she, who attended the Owyhee Combined School in the 1970s, worries she could get cancer, too.

“Most of us, all my classmates, are gone too,” Blossom said. “All from cancer.”

‘If you can’t grow plants … how can we educate our children there?’

Mason, who has worked as an environmental engineer for eight years in the state’s Leaky Underground Storage Tanks program that cleans up closed mine sites in Nevada, grew more concerned about the school when the tribe tried to build a new greenhouse on Bureau of Indian Affairs’ land and was denied.

The tribe partners with the Bureau of Land Management for advice on the tribe’s greenhouses, which it uses for economic development, growing sagebrush for fire restoration, mine restoration and habitat improvement. The two entities were going to partner with the Bureau of Indian Affairs on another greenhouse, but the Bureau of Indian Affairs did not want to transfer the land to the tribe because of the “liability of the plume,” Mason said.

“And so we thought, ‘Well I mean, if you can’t grow plants because of liability, how can we educate our children there?’” Mason said.

While the contaminated water source was cut off from the school, the tribe has not sampled any of the old pipes inside the school to see if the contaminants remain.

“Because once we do that, we won’t have a choice but to close the school,” Mason said. The reservation is 100 miles from the next town, Elko. How does Elko County School District and the tribe plan to bus 400 students every day two hours away? Mason said.

In ‘survival mode’

Besides the possibly contaminated pipes, other areas of the school are in disrepair. Part of the roof is failing, some parts of the outside brick wall show signs of water degradation, and some classrooms’ floors are warped due to heating issues. A playground on school grounds is also in disrepair and unsafe for children to use, Manning John said. The entrance doors are also made of glass, and school staff are concerned about students’ safety if a school shooting were to ever occur.

The school, built to hold 120 students, holds about 400. It is so overcrowded, Mason said, that there is no teachers’ lounge, forcing the teachers to eat their lunches in their cars.

Thacker’s 5-year-old daughter in kindergarten shares a crowded trailer classroom with the pre-K class, and the trailer is not in good condition. Her kids also complain about either being really hot or really cold in the classrooms, although the issues with the heating were present when Thacker went to the school as well as a student, she said.

“I just feel like (for) all these years, our staff, our community and our kids just make do with what they’ve got,” Thacker said.

There is no safety barrier between the school and the highway, besides a small parking lot, Manning John said. Occasionally trucks will go around a curve nearby, and the trucks’ cargo will fall out. One time, that cargo was cattle, she said.

Students who drive to school have to cross the highway to get to their cars, and they sometimes drive their younger siblings to school, so there can be 16-year-olds and 6-year-olds crossing the highway, she said. Crossing guards aren’t always available.

The school also does not have functioning internet, Manning John said. The internet will go out at random times of the day, and if classes need to do online testing, they must be staggered at different times so the bandwidth can support it. When it comes to conducting SATs, the school does it with paper because the stakes are so high, Manning John said.

“If we weren’t in survival mode all the time we could thrive, but because we’re addressing these daily student safety issues, we’re just trying to make it through the day with internet glitches,” Manning John said. “We would take more pride in ourselves, in our communities.”

The building itself also contains a painful history within its walls. Around the same time of the infamous boarding schools around the country that strove to “kill the Indian, save the man,” students in Owyhee had to “shed their Nativeness at the door,” Manning John said. Her students’ grandparents were punished for speaking their Native language in the hallway, she said.

“There’s a lot of historic grief attached to the teaching of our people,” Manning John said.

“These kids have a challenge with life just by being Native American,” Mason said. “You know, (Native Americans have the) highest suicide rates,” Mason said. “I think last year during COVID, we had nine in the community. … It’s depressing. And the school is, you know, where they all go to bond, where they make friends, where they start their lives.”

The new site

The tribe recently approached the Elko County School District, which leases the tribe’s land for the school for $1 a year, and the district suggested that it pursue a one-time funding bill in the Legislature. The tribe estimates it will cost $77 million to build a new school, and it has already set aside 80 acres of land.

The tribe is currently looking for a legislator to sponsor the bill in the 2023 session. Assemblyman Howard Watts III, D-Las Vegas, who has been a strong voice for Native American rights in the past and is introducing a couple of different bills that aim to help Indigenous folks in Nevada, was not aware of the tribe’s efforts, but said in an email he is open to any proposal on the school that came to the Legislature.

Mason, who became chair four months ago, does not understand how the problem with the school has gone on for so long without getting fixed. He thinks it is partially because the tribe and the reservation is “out of sight, out of mind” from the rest of the state.

“We’re the furthest north community there is in Nevada,” Mason said. “It is an Indian reservation; we’re an underrepresented demographic group.”

Manning John already has a site picked out for the new school. It is adjacent to one of the tribe’s subdivisions where 70 percent of the students live, not in Owyhee but in the community called Newtown, away from the highway. It is about three miles out of town, and up the east side of the mountain.

“Should we be able to see this through, the impact on the community is beyond what any legislature or person outside the Duck Valley community even knows,” Manning John said.

Bills would help Native Americans in Nevada

The Nevada Legislature is set to consider a number of bills in the upcoming 2023 session that will affect Native Americans in the state. Here’s a look at some of them:

Free state park entry - Assemblyman Howard Watts III, D-Las Vegas, has a bill draft request that would provide free state park entry and usage for members of Nevada tribes.

Most tribes in Nevada never signed a treaty, Watts said. “They were just displaced from their ancestral homeland,” Watts said. “We want to make sure people have access and can enjoy those areas without financial barriers.”

Tribal liaisons - Introduced during the Interim Natural Resources Committee, the bill draft aims to support the hiring of tribal members to state government for tribal liaison positions, Watts said.

Missing and murdered - Assemblywoman Shea Backus, D-Las Vegas, has a bill draft request that will establish a system where tribes can report to local law enforcement when someone goes missing so that the case can get into the right databases faster, Backus said. The legislation will “really help and have an efficient way to report when someone goes missing from one of our tribal communities,” Backus said.

Indian Child Welfare Act - Backus has another bill draft request that would protect the Indian Child Welfare Act in Nevada in case it gets overturned federally. The legislation from 1978 provides guidance to states regarding the handling of child abuse and neglect as well as adoption cases involving Native children, according to the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. There is a pending supreme court case called Brackeen v. Haaland that could overturn the legislation.

Other changes sought by Native Americans

Janet Weed, tribal administrator for the Yomba Shoshone Tribe, said she would like to see tribes, particularly the Yomba Shoshone Tribe, benefit from the changes to the taxation of mining companies that was improved in the last legislative session. Taxes of mining companies were increased, with much of the funds going toward education. Much of the land that the gold and silver mines are on is Shoshone land, Weed said.

“If the state is increasing the mining tax, why isn’t the tribes benefiting?” Weed said.

Weed would also like to see tribes’ gaining clear ownership and management of their water, and she would like to see tribes get their hunting rights back.

“We know when it’s the time for hunting. We want to hunt in our inherited lands in our own way,” Weed said. Instead, tribal members have to apply for a tag like everybody else.

“We’re not exempt from having to apply and follow the state regulations to hunt,” Weed said. “Who knows from the land (than) the Indian people, the Shoshone people?” Weed said.

Other states have similar allowances in place. In Massachusetts, for instance, members of federally recognized tribes have the aboriginal right to fish and hunt to feed their families as long as they have a tribal ID, regardless of local laws prohibiting others to do so.

Teresa Melendez, CEO of Tall Tree Consulting, which helps Nevada tribes connect with legislators, said she has heard from multiple tribes that they would like to see some changes to the tuition waiver bill that passed in the last legislative session to expand to others who are not currently included. Tribes would also like to see changes to the law passed in the last session barring the use of racially discriminatory names and symbols from public school districts to make it more enforceable, Melendez said.

“We wanted to put some teeth behind it,” Melendez said.

Tribes also want to revise voting laws to make sure tribes automatically get a polling location in their tribal community. If a tribe does not want a polling location, then it can opt out, Melendez said. As the law exists now, tribes have to request a polling location, but some clerks are not honoring that request, Melendez said.

Contact Jessica Hill at jehill@reviewjournal.com. Follow @jess_hillyeah on Twitter.