COMMENTARY: I was homeless: Here’s what I learned

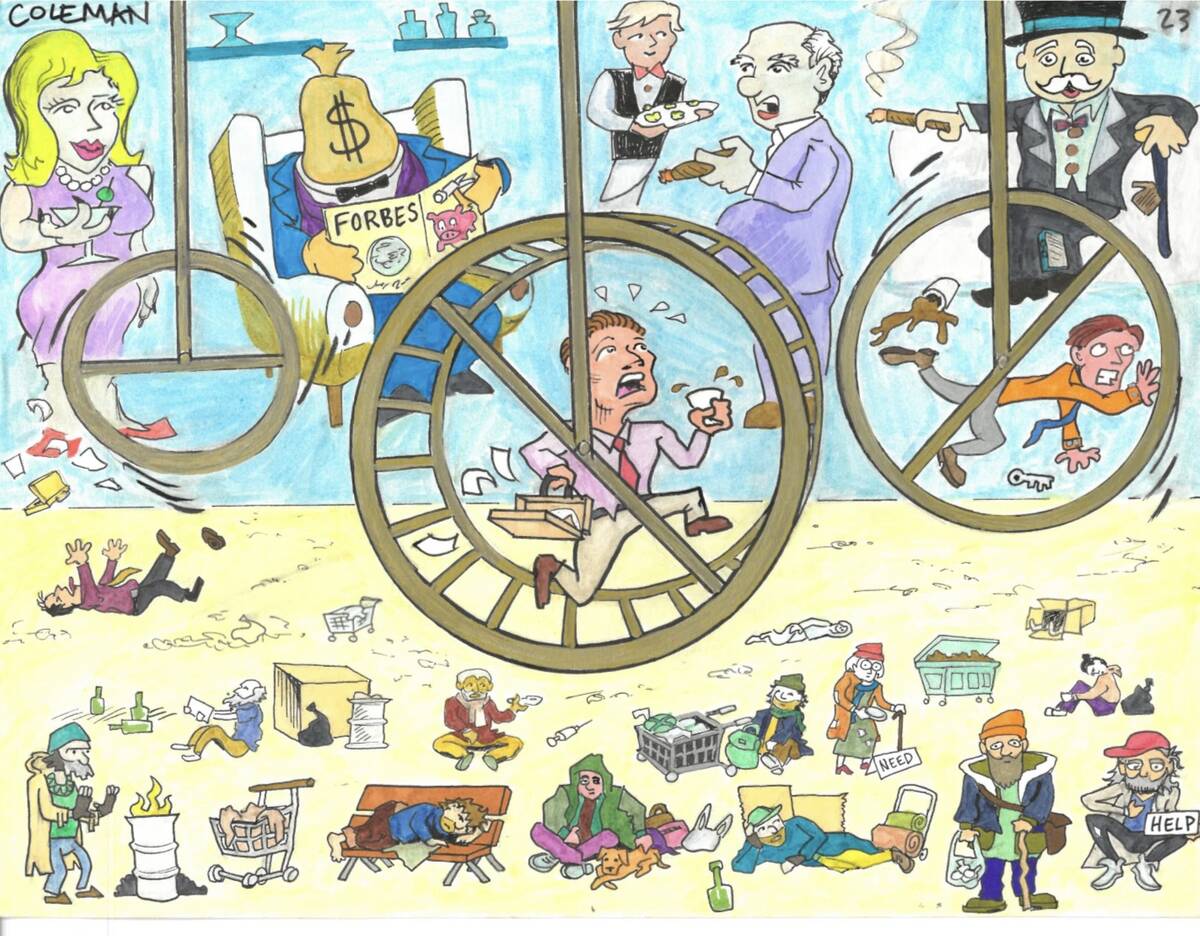

As the National Park Service in D.C. continues to break up homeless encampments, pushing them from one neighborhood to another, it’s clear our unsheltered homelessness problem isn’t going away anytime soon.

In 2022, Washington had an estimated homeless population of 4,400. About 690 were unsheltered. Though the total homeless population has decreased recently, the number of unsheltered homeless has remained stubbornly high.

Uncomfortable as we are with the unsheltered, we citizens largely abdicate our role in helping the homeless directly and leave the job to our government, which consistently struggles to fix the problem. While our government infantilizes them with paternalistic policies and vague rhetoric of compassion, citizens have learned the dehumanizing art of ignoring them altogether. By failing to engage with the homeless as fellow citizens and holding them to our own standards of acceptable behavior, we inadvertently perpetuate their disruption and neglect our role in fixing the problem.

Rural areas are no exception to the growing problem in the country. Pahrump’s unhoused population has surged during the pandemic — the county has no shelter and RV encampments have attracted a number who live in our deserts in unsanitary conditions without water or electric.

I don’t say that without compassion: I see myself in all the wretchedness, mental illness and anger reflected in the eyes of the homeless.

When I was 20, a spat of severe depression cost me my job. Unable to make rent, I wound up homeless, and, for a month, I wandered the streets feeling isolated and bitter. I needed help and was starving for even an ounce of compassion. Yet, many who might claim to have compassion for the homeless would walk right by me without offering even a glance. In ignoring me, it felt as though they denied my humanity.

But I don’t blame them. Years later, once again employed and housed, I find myself grappling with the same aversion that caused others to avoid me when I was on the street. Even though I know first-hand how harmful it is to be denied recognition from the other side of the street, it’s clear to me that, in helping others, we put our goodwill on the line: Without some assurance of mutual respect and decency from those on the receiving end of that goodwill, few of us will take any chances. To do our part in helping our homeless neighbors, we must also hold them to a higher standard.

The only people who deserve unearned decency, kindness and assistance are young children: Pretending that every homeless person deserves such help only infantilizes them. The homeless must conduct themselves appropriately to expect recognition or help; individuals should comply only insofar as they are willing to reciprocate our respect.

A few months ago, I was on my lunch break, sitting outside of a fast-food joint, when a man approached me. His ragged clothing marking him homeless. I greeted him, and he awkwardly asked if I would buy him lunch. I said I would, igniting a light of thanks in his eyes. We hardly made it into line before someone behind the counter noted the man’s appearance and demanded that he leave. I assured her I was paying for his food, but she ignored me, ordering him to leave and threatening to call the police. I don’t know whether she was upholding store policies or recognized him from previous encounters.

But the moment of happiness that had lit his eyes at my promise instantly faded, and he began to yell at the worker, hurling obscenities at her. The store employees called the police as he fled.

I had tried to help him because of my compassion for his plight. My compassion was built on a respect for his status as a fellow citizen, whose shoes I might imagine myself in and from whom I might expect reciprocated decency and respect. Though I understood his anger at a society that had rejected him, his behavior showed they were right to do so and betrayed my expectations. If he begged me for food again, I would not assist him. Only when we maintain such expectations do we have a standard that allows us to set aside our aversions and recognize the homeless, separating the decent from the indecent.

Too often, citizens place the duty to act upon institutions, which ultimately leads to our abdication of the productive role that we can play in helping the homeless directly. Part of what makes homelessness so miserable is the subhuman self-image created when people ignore you. By recognizing the homeless and showing them the basic respect that we extend to others, we can do our part in mitigating their misery. We will often find decent people underneath the rags.

Genuine respect for a person entails more than compassion and no-strings-attached assistance — it requires that we have expectations of them, as we do for all adults. This respect can have a real effect in helping the homeless improve their self-image and moving them toward self-sufficiency. It isn’t a grand way to show your morality, and it won’t always fix things, but taking a small risk could make the difference in turning someone’s life around.

Jeremiah Ludwig is an economist in Washington. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.