EDITORIAL: A retail theft conspiracy?

California lawmakers this week passed a series of measures designed to discourage retail theft. It’s an odd response to a problem that progressives insist doesn’t really exist.

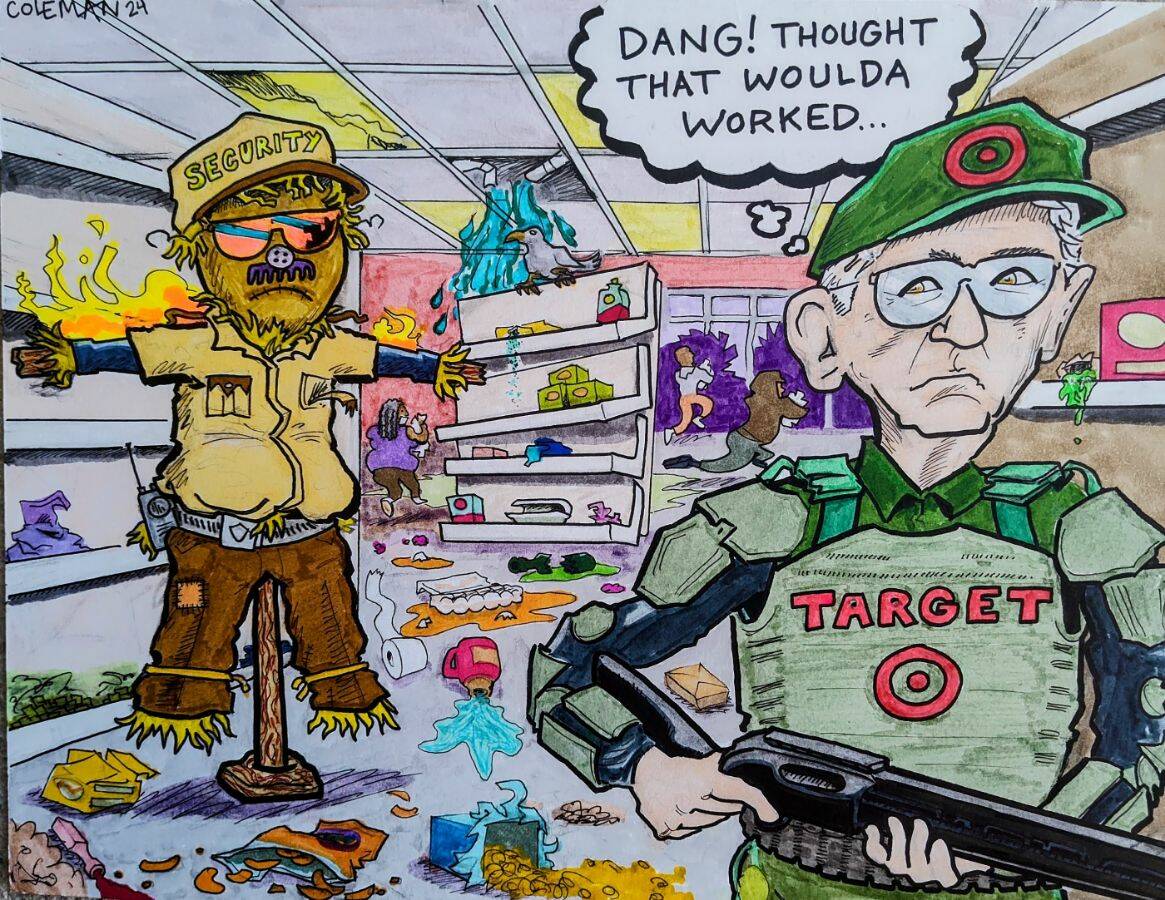

In recent years, several major retailers — including Walgreens and Target — have closed stores in major cities, citing rampant shoplifting. Some chains have put common products in locked cases to discourage “shrinkage.” Viral videos show gangs going on “smash-and-grab” sprees.

All this has come as Democrats in several states, including California and Nevada, have relaxed punishment for such thefts as part of criminal justice reform.

Yet official crime statistics show that retail theft has remained flat, according to the New York Times. This has led many on the left to accuse greedy capitalists of exaggerating the problem to cover up mismanagement. Democrats also charge Republicans with creating a false narrative for political gain.

But that’s highly conspiratorial. Why would retailers — who have firsthand experience with the costs of shoplifting — go to the expense of protecting inventory and closing locations if reports of rampant theft were overblown? At least as likely is that statistics aren’t telling the full story because so many incidents go unreported. “Companies do not share data on goods stolen, let alone stolen in a specific manner,” NPR acknowledged in a March story. “And individual stores often don’t report incidents to the police.”

Indeed, a recent CNN report notes how many major retailers now take a more active approach to controlling theft. “A CNN review of court records and interviews with more than two dozen retail and law enforcement officials,” the network noted this week, “shows that persistent problems with sophisticated organized crime networks have led many private-sector companies to not only assist law enforcement but to often deliver the bulk of the evidence that leads to criminal prosecutions.”

Home Depot, for instance, has “invested in police-like investigation centers to sift through data and pinpoint theft-group members,” CNN reports. One retail crime manager for Kroger “said his company has heavily invested not only in its investigative capacity but also visual deterrents. For example, the company purchased an old police car to drive around parking lots to ward off would-be criminals.”

That’s a lot of trouble to attack a fictional problem.

Whatever the true statistics on retail theft, state politicians haven’t improved the situation by easing penalties and telegraphing to potential shoplifters that they can ply their trade with impunity. If you make it easier for criminals to operate, you are, in effect, subsidizing crime. The fact that Democrats in California and elsewhere are now rushing to mitigate the political fallout of their own failed policies is simply par for the course.

This commentary initially appeared in the Las Vegas Review-Journal.