Nevada law allows probate house sales with less oversight

Nevada attorneys made big promises when they pushed for a change to probate law more than a decade ago.

The proposed new way to sell dead people’s homes and settle their finances would speed up cases, reduce burdens on the court and slash costs, they said.

All told, case administrators could act more independently, as court supervision was in many cases “neither helpful nor necessary,” proponents told lawmakers.

Since then, two prolific administrators used the legal provision hundreds of times combined in Southern Nevada. They also routinely started those cases without family participation, often generated no sales proceeds for heirs and frequently sold homes to a small circle of buyers who flipped the properties, a Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation found.

Probate cases involve transferring ownership of a dead person’s property through court and settling debts. Under the “independent administration” option Nevada lawmakers adopted in 2011, a house can be sold without a judge’s approval or competitive bidding through court, probate attorneys said.

It’s a useful tool when family members agree on what to do with property a dead relative left behind, according to attorneys. Heirs can sell the home faster through court and move on with their lives.

But by design, this route through probate court provides less oversight of the sale and no court-supervised bidding process that might push up the price.

“There’s no accountability,” said Donnalyn VanOrman-Wasano, a private fiduciary in Henderson who works with trusts and estates.

State Sen. Melanie Scheible, D-Las Vegas, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the last two regular legislative sessions, said Monday she found it troubling that people were profiting from the deaths of individuals whose families did not take over the estates.

It’s too early to say whether any laws need to be changed, said Scheible, who believed the issue “definitely deserves” some attention from Nevada legislators.

“It kind of sounds like there’s a loophole here,” she told the Review-Journal.

Assemblywoman Brittney Miller, D-Las Vegas, chair of the Assembly Judiciary Committee in last year’s session, did not respond to requests for comment.

Frequent court approval

Court officials were aware of “concerns and trends” in probate cases and, in response, imposed greater scrutiny on third-party administrators early last year, District Court spokeswoman Mary Ann Price said.

There have since been fewer requests for independent administration, she said.

Two of Southern Nevada’s most prolific private administrators of the past decade, Thomas G. Moore and his probate successor Cynthia “Cyndi” Sauerland, were involved with at least 500 probate cases combined in District Court over the last several years.

They also sought independent administration virtually every time, and the court routinely granted it.

Many of their cases started without family on board. In roughly 80 percent of his initial petitions to oversee cases, Moore did not identify any known heirs or he named them but stated he could not communicate with them, the Review-Journal found. For Sauerland, that figure was around 73 percent.

Moore, founder of Estate Administration Services, obtained court authority for independent administration in at least 340 cases among 345 requests tracked by the Review-Journal.

Sauerland, an agent with Compass Realty & Management, secured this authority at least 125 times among 153 requests, court records show.

Ultimately, the duo sold at least around 360 homes through probate court, and their three biggest buyers alone flipped more than 130 homes for $13.4 million above the combined purchase price, the Review-Journal found.

Las Vegas probate lawyer Kennedy “Kenny” Lee said independent administration, in general, offers more control over who buys the home. The family might want to sell to a friend, for instance, even if that person can’t pay top dollar, he said.

But selling with court confirmation allows for a bidding process, and depending on market conditions, buyers might push up the price, he said.

‘It’s a quicker process’

Under Nevada law, almost anyone can manage a probate case. Family members have top priority, but last on the 10-deep list in state law is anyone “legally qualified” for the task.

It’s a low bar, as any adult in Nevada can run a probate case if the person is not a felon. Would-be administrators also could be blocked over a conflict of interest, “drunkenness” and “lack of integrity,” state law says.

Moore, Sauerland and their associate Adam Fenn of Compass Realty contend they are finding buyers for abandoned houses that can be taken over by squatters, fall into disrepair and become a neighborhood nuisance.

VanOrman-Wasano also noted that it can take a while to get a court hearing on a sale and that sometimes she worries the homes can fall prey to squatters or vandals or end up in foreclosure.

Moore, who is 41 and now lives in Washington state, said his legal counsel recommended using independent administration because of the issues with abandoned real estate.

“Moving quickly was in the best interest of the situation due to debt accruing daily and the condition of each property deteriorating daily,” he told the Review-Journal in an email.

More often than not, heirs received nothing from his probate sales.

Moore sold 230-plus homes through probate court. On at least 164 occasions, he reported having nothing to distribute to heirs because he sold the home in a short sale, court records indicate.

In such transactions, lenders approve a sale for less than what’s owed on the seller’s mortgage, typically because the property value fell.

Sauerland also pointed to problems the homes can face after the owners die and said the sooner the properties are dealt with the better.

“It’s a quicker process, but that’s not to mean that we’re trying to race to the end and just make a bunch of money and run away,” she said.

According to Sauerland, 65 percent of her sales had equity for the estate.

Overall, the court’s probate workload is plenty high: As of 2022, three judges presided over 10,000-plus probate cases in District Court.

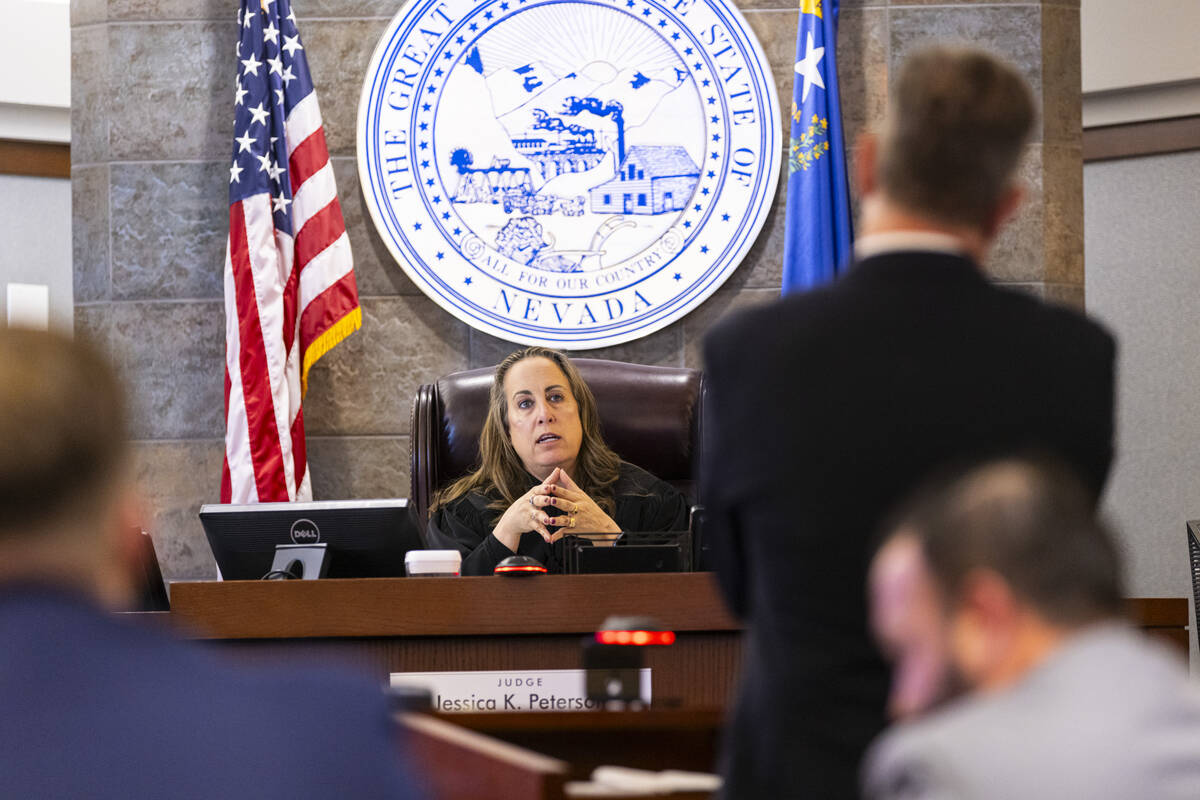

Probate judges, including Gloria Sturman, who took the bench in 2011, and Jessica Peterson, who took the bench in 2021, and Probate Commissioner James Fontano did not respond to requests for comment.

Fontano was appointed to the job in fall 2022. As Price described it, he implemented the new requirements after consulting with judges.

Former Probate Commissioner Wesley Yamashita, who held the job from 2008 to 2021, declined to comment.

‘Some formalities can be relaxed’

In 2011, Senate Bill 221 made various changes related to trusts and estates. Among other things, it contained the Independent Administration of Estates Act, which allowed a personal representative to administer “most aspects” of a dead person’s estate “without court supervision.”

After the bill was introduced, the State Bar of Nevada said the independent provision was designed to expedite probate cases, reduce burdens on the court and lower administrative costs by allowing a personal representative “to act more independently from the court in non-contested matters.”

“In many estates, court supervision is neither helpful nor necessary, and some formalities can be relaxed without any detriment to the interested parties,” according to a summary the legal group provided.

There may have been some attorneys who voiced concern about independent administration at the time, but the State Bar’s probate and trust section felt the “benefits outweighed the burdens” of “what could go wrong,” said Reno attorney Julia Gold, one of the lawyers who pushed for the change.

Gold said she has heard that Las Vegas gets some “disturbing” probate cases. But overall, independent administration fulfills its intention of lowering expenses and getting more money to beneficiaries, she contends.

“If it’s used properly, it serves its purpose, and it serves it well,” she said.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Segall is a reporter on the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders, businesses and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Michael Scott Davidson, the Review-Journal’s former data/watchdog editor, contributed to this report.