Twentieth anniversary of one of Death Valley’s baffling mysteries

This July marks 113 years since the world’s record 134-degree high temperature was recorded at Furnace Creek in Death Valley National Park, nearly 30 years since the Badwater 135 ultra endurance race became an annual event, and 20 years since a small group of tourists from Germany mysteriously disappeared in the desert outback.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part article. The second will run Friday.

For 40 days and 40 nights in the summer of 1996, the Death Valley desert shimmered and undulated in waves of relentless record-breaking heat, pushing the national park thermometers over 120, and sometimes 130 degrees. The fervid air sucked the moisture from the breath of park visitors and stole the sweat from their skin. Even in the cooled rooms of the park’s hotels, travelers labored under the weight of one of the hottest summers on record in the hottest place on earth.

Into the mouth of this furnace, on July 22, drove an impetuous 33-year-old tourist named Egbert Rimkus on holiday from Germany with his new girlfriend, 28-year-old Cornelia ‘Conny’ Meyer, and two small boys (one hers and one his). Piloting a rented green Plymouth minivan, low on cash, short on time, poorly stocked and unprepared, Rimkus headed for the park’s unforgiving backcountry. Guided only by a simplified visitor’s map, he and his passengers left the heat-softened asphalt behind and made their way along a dirt road at the southern end of the park.

Heading for higher elevations, where the air was cooler and more breathable, the van traveled west toward the Panamint mountain range. Inside the air-conditioned Voyager, its inhabitants were probably as cheerful and optimistic as only strangers in this strange land could be.

While the van gained altitude, a small group of extreme athletes in the valley below were heat acclimating for the annual summer race across Death Valley’s Badwater basin. The athletes, carefully vetted by a diligent team of organizers, had been training for months to brave the Badwater crossing. Beginning at the lowest point in North America, the 135-mile course would take them out of the national park and up to Whitney Portal, gateway to Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the Sierra Nevada range.

But first, they would pass at a slow pace through the oven of Death Valley, followed every step of the way by teams of support personnel. That year, the record high temperatures would add to the growing international reputation of Badwater 135 as the ultimate endurance run, and the toughest foot race in the world.

In the backcountry, Rimkus and Meyer and their children—his son Georg Weber, 10, and her son Max, 4, spent the night in Hanaupah Canyon near Telescope Peak, where they camped and played and posed for touristy pictures. The dirt road into the canyon was rough, but the Voyager had managed it without incident, perhaps creating a false sense of confidence about what those broken, off-pavement lines on the visitor’s map actually signified.

The next day, still traveling passable dirt roads, the travelers arrived in Warm Springs Canyon. There, under an unexpected leafy green canopy, they found the chipped and cracked old concrete cabins built in the 1930s by a woman named Louise Grantham. She had become one of the richest miners in Death Valley and in her heyday had employed a cook staff to serve hearty meals in the airy dining hall. The camp where she and her workers had lived was quiet now, having been abandoned for decades. But visitors could still find fresh water in a mountain spring, shade trees and cool concrete to shelter them from the sun.

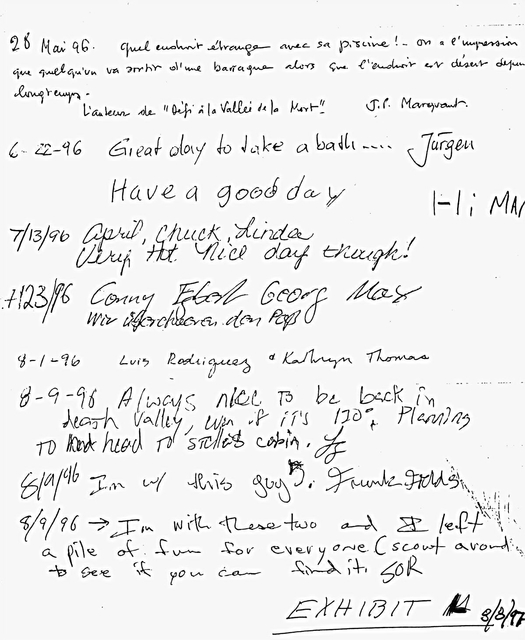

In a metal box on a pole at the edge of the camp, Conny Meyer found a visitors’ log. “Going through the pass!” she wrote in German, and signed all of their names. It might have been an exuberant declaration, or a sort of bread crumb left in a moment of misgiving about the trail ahead. Beyond the camp lay Mengel Pass, where easy water and shade trees became distant memories and only rock-crawling four-wheel drive vehicles were advised to go. But on the map, it looked no different than the road to Hanaupah.

Driving the Voyager along the rutted mining road, they arrived at a solitary old structure known as the Geologist’s Cabin, maintained by volunteers to provide shelter for visitors. Here, in a fit of mischievous chutzpah, the German visitors commandeered an American flag to bring home as a souvenir.

Down below, on the valley floor, the Badwater 135 runners began their race, pitting themselves, highly conditioned, optimally outfitted and fully supported, against the desert heat.

The four Germans, poorly equipped and alone, wandered further into the desert back country.

While the runners made deliberate, carefully measured progress across the valley, the Voyager took one wrong turn after another. Retreating from the obviously impassable Mengel Pass, the van diverted down into Anvil Canyon on what was left of another old mining road. Careening between progressively deeper ruts and bumps, the Voyager soldiered on until the tires popped and shredded and the axle hung up on a rock.

With visions of the cool air atop Mount Whitney, the runners on the valley floor pushed through the searing heat.

The Germans, clinging to the only shade in sight, stuck close to the van for some time, wondering what to do, consuming much of what was left of their supplies. At some point, probably as the sun began to go down in the evening or early the next morning, the Germans left their vehicle and set out on foot and carrying their meager provisions, mostly beer and wine, along with them.

For years afterward, it would be assumed that they had tried to make it back toward the cabin or Mengel Pass—better the devil you know than the one you don’t. But they didn’t.

Only 61 percent of the athletes who entered the Badwater marathon would complete the course that year, the lowest percent in the recorded history of the race. Extreme endurance athlete Marshall Ulrich was the winner, with 1996 being the first of his record four Badwater wins. Runners have described the Death Valley experience as cathartic, revelatory, and exhilarating.

But for the average person lost in the heat of a Death Valley summer, the chances of survival diminish rapidly from the moment the last drop of water is consumed, with about a two-day outside limit for survival.

Mike Wehmeyer, volunteer Emergency Medical Technician for the National Park Service, says this guideline pertains to a healthy adult who is well hydrated to begin with.

For small children, for adults who are already on a hydration deficit, for anyone out of shape and not acclimated to the heat, the survival window can narrow to a matter of hours.

The race was over on July 27 and the runners left Death Valley to its stillness. In Germany, Rimkus’ ex-wife Heike Weber waited anxiously for her son Georg to arrive back home. The day came and went, with no word from Rimkus. He had faxed her from the Treasure Island Resort in Las Vegas over a week before asking for money, which she had not sent. And now she wondered what he was up to.

Frantic faxes from a German travel agency begged for information from the U.S. rental car agency that had dealt with Rimkus in Las Vegas. “We worry, worry,” said a fax from the travel agency on July 31, but a bewildered clerk could offer little comfort. The agencies reported the disappearance to Interpol, but there were no real leads to go on.

Rimkus was described as a “go-getter and adventurer” by his ex-wife, unpredictable and clever enough to think up any number of schemes. For the next three months everyone involved waited and worried, but most clung to the notion that Rimkus had staged this disappearance and stolen the children.

Then in late October, a routine drug surveillance plane flying over Anvil Canyon spotted the missing Voyager van. It was abandoned and covered with a layer of dust. On the ground, NPS Investigator Eric Inman responded to the radio call and was the first to approach the locked vehicle. When he looked in the window and saw a child’s shoe on the seat, “my heart broke,” he said.

The NPS and Inyo County Sheriff’s Office mustered over 200 search and rescue workers, eight horses and four helicopters to comb the area around the van, searching for answers. They found only a few footprints and empty bottles leading off into the empty beyond.

The four Germans tourists had disappeared without a trace.

Robin Flinchum is a freelance writer and editor living in Tecopa, California. Her book, “Red Light Women of Death Valley,” was published last year.