Ethics questions haunt sheriff’s captain, documents reveal alleged abuse of power

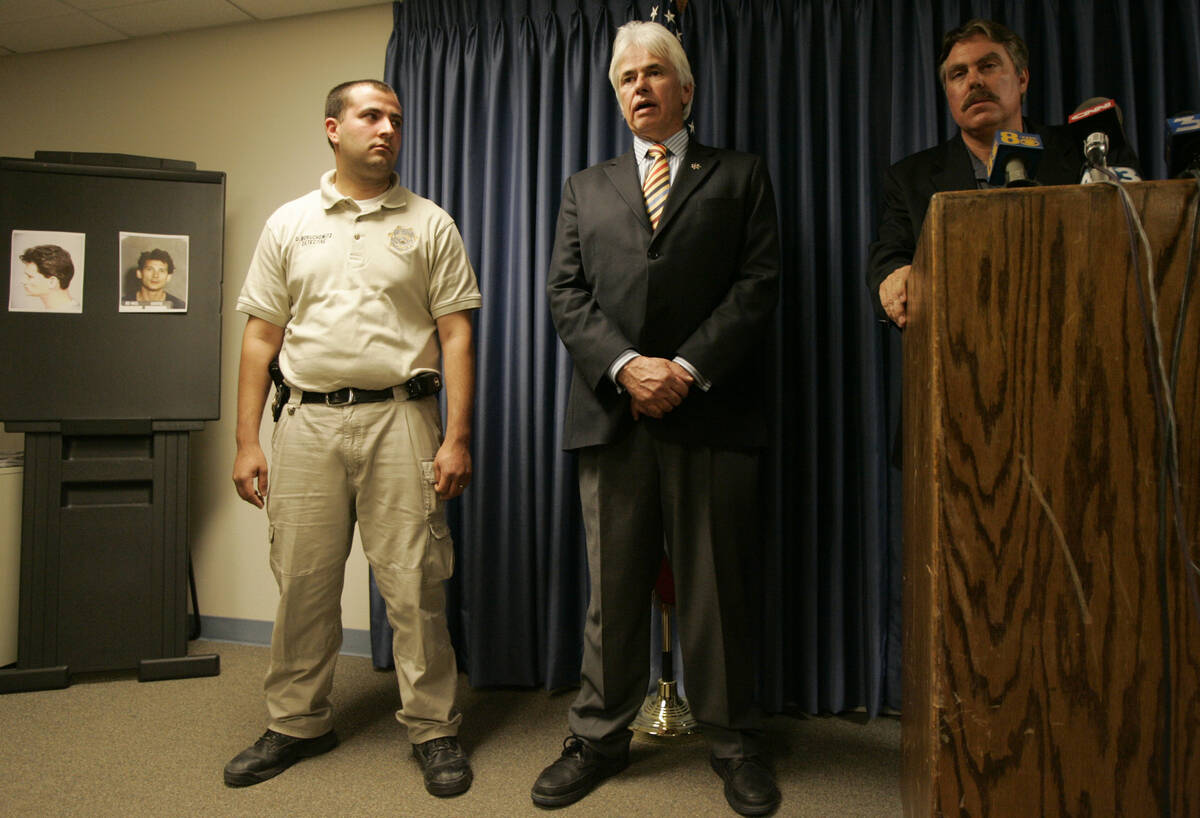

Nye County Sheriff Capt. David Boruchowitz has put himself front and center at news conferences, high-profile investigations and in social media videos. He’s appeared in police reality shows.

But Boruchowitz’s history includes conflict-of-interest allegations, multiple lawsuits and liability claims, a state probe into him holding “porn matinees” at the office, and an FBI investigation into whether he had inappropriate relationships with criminals.

Despite wide-ranging accusations that he has abused his power for years, he has escaped serious discipline, which flies in the face of the growing movement for police accountability. He is now paid more than his superiors. And Sheriff Sharon Wehrly, who Boruchowitz, as a former union president, endorsed during her first run, has repeatedly promoted him since taking office in 2015.

Leslie Peeler, who was commander of the state Department of Public Safety’s Office of Professional Responsibility when it investigated Boruchowitz nearly a decade ago for showing porn at work, was surprised to hear Boruchowitz was promoted.

“We have fired people for not nearly that bad of conduct,” said Peeler, who retired in 2018. “It bothers me as a professional.”

New court documents highlight the latest controversy: Boruchowitz helped form a Nye County activist group, Members for Change, to remove the Valley Electric Association’s leadership at the same time he was overseeing a high-profile 2019 arrest of the co-op’s top executive, CEO Angela Evans, depositions show.

In fact, Boruchowitz was thinking of running for a paid position on the board, which paid up to $28,000 a year, according to testimony in a federal lawsuit filed by Evans. She is claiming unlawful arrest and violations of her civil rights.

Members for Change worked to replace the VEA board after concerns about residential electricity rates and broadband price hikes.

Boruchowitz also testified in a deposition that he did not tell the justice of the peace who signed the VEA search warrant about his potential conflicts in the ongoing probe. And in an audio recording he made in February 2019, Boruchowitz and former VEA executive Ken Johnson discuss an envelope of cash Johnson wanted to give Boruchowitz. Boruchowitz tells Johnson not to give him the money at this time, “to avoid the – any appearance of impropriety.”

Days after the recording, Boruchowitz arrested Evans on suspicion of embezzlement for allegedly using association funds to pay for burying power lines at her home, but the case was so flawed Nye County District Attorney Chris Arabia declined to prosecute in December 2019.

Evans’ October 2020 lawsuit against Boruchowitz and the county says he deprived her of her constitutional rights by “arresting her without probable cause or justification and by intentionally misleading and deceiving the court into granting the search warrant, which caused and allowed the unlawful arrest.” She lost her CEO position in July 2019 and said she has “been destroyed.”

“I have the utmost respect for law enforcement. Utmost. It’s how I was raised. But he is a dirty cop,” she said of Boruchowitz in an interview with the Review-Journal last month. “He runs Nye County. And Sheriff Wehrly doesn’t know enough about her job.”

Wehrly still surprised Boruchowitz with a command excellence award last year. That same year, he made $119,000 — about $18,000 more than Wehrly’s base salary.

Boruchowitz, in emails to the Review-Journal, titled “Journalistic Witchhunt,” initially offered to provide records and an interview after the news organization made multiple public document requests to the county.

“It is clear from the public records that you are requesting that you are being fed information from the same group that has been attacking me for years,” he wrote about attorneys and former Nye officials who have made misconduct allegations against him. “I have always been an open book, willingly participating in journalistic interviews, and allowing journalists to see whatever is needed to quell their witchhunt fueled by someone else.”

But two hours before the scheduled January interview in Pahrump, he emailed that he had to cancel, refusing to even come out of the warehouse-like sheriff’s office to be photographed. He later emailed saying he would only take written questions.

The Review-Journal declined to provide questions but emailed him topics to discuss and suggested a Zoom interview. He didn’t respond to that email. Wehrly also declined an interview, saying she can’t discuss personnel matters and pending litigation. Her staff repeatedly refused to release records about Boruchowitz’s internal affairs disciplinary history.

Misconduct concerns

Nye County is known for having a freewheeling, anything-goes attitude toward the legal brothels, pot shops and fireworks stands that bring in tourists visiting Las Vegas. With a population of about 50,000, the area is seeing steady growth as it serves as a bedroom community for people who work in the metro area but want bigger houses on more land at a much cheaper cost.

The town of Pahrump remains the population center of Nye County, the nation’s third-largest county by area, containing about 75 percent of the county’s overall residents. The sheriff’s office has nearly 300 deputies, dispatchers, corrections workers and other staff covering more than 18,000 square miles.

Wehrly herself has been under fire for provocative actions and comments. She posted recruitment billboards in 2018 that her critics said were political campaign ads in disguise. She said her department would not enforce the governor’s statewide closure decree on local businesses in March 2020 for COVID-19, and invoked Hitler when refusing to enforce the state’s new gun background checks law in 2019.

Association and internal sheriff’s policies prohibit officers from using their positions for personal reasons.

The American Correctional Association ethics guidelines, on which Nye sheriff’s staff were briefed, prohibit securing “personal gain” and “personal privilege or advantages” during official actions. And Nye sheriff’s policies prohibit “financial or other personal interest, directly or indirectly, which is incompatible with the proper discharge of the employee’s official duties, or which would tend or appear to impair the employee’s independence of judgment or action in the performance of official duties.”

Frank Rudy Cooper, UNLV law professor and director of Boyd Law School’s program on race, gender and policing, said federal and state officials can only step in when there is a pattern of constitutional rights violations.

“This may be more of a political problem and people have to hold the sheriff to account,” he said.

Botched embezzlement case

Evans was arrested on Feb. 26, 2019, for suspicion of embezzlement of $3,500 or more over accusations that she billed the VEA for about $89,000 to move power lines underground on her personal property in Pahrump, according to documents. After reviewing records, police reduced the work estimate to about $75,000.

But property records show she purchased the house after any VEA work was completed. Evans was cleared in April 2019 of any illegal conduct in a report the VEA commissioned.

In the Evans lawsuit deposition, Boruchowitz conceded he never revealed to Nye County Justice of the Peace Lisa Chamlee, who signed the search warrants, that he and Johnson formed the Members for Change group. He testified that he created the group’s logo, built the group’s Facebook website and set up a phone line.

Chamlee declined to comment through a court administrator.

Johnson, in a January interview, said Boruchowitz distanced himself from the group after the criminal investigation started, but he couldn’t comment on whether Boruchowitz had a conflict.“I would expect him to know what he should and shouldn’t do,” he said.

In the deposition, Boruchowitz testified that NCSO never investigated his actions in the case.

Wehrly testified she knew Boruchowitz considered running for the energy cooperative’s board. She said she didn’t know he was in Members for Change but wasn’t concerned by the potential conflict.

“I would have looked at it, yes,” Wehrly said in her June 9, 2021, deposition. “But I don’t know whether it would have really concerned me or not.”

And in a recording Boruchowitz secretly made of his discussions with Johnson, which his attorneys had to turn over as part of the discovery, Johnson and Boruchowitz discussed cash.

“Hey. I’ve got an envelope for you in here,” Johnson said in the recording.

“If the envelope is your half, keep it for right now,” Boruchowitz responds. “The fact that this may go criminal, keep it to avoid the – any appearance of impropriety. And then at the end, we can — we can figure out what we are going to do. Let’s — let’s keep it clean.”

Johnson then tells Boruchowitz, “Don’t go spending a bunch of money.” Johnson told the Review-Journal that the envelope contained $50 to $100 to pay for the group’s Facebook ads, and the “spending a bunch of money” comment was just something his stepfather said after giving people cash. It was unclear why Boruchowitz made the recording.

Evans, in an interview and court documents, alleges there was a conspiracy between Boruchowitz and Johnson to violate her rights. “That’s called bribery,” she said about the recorded conversation. “And, you know, you’ve got those two individuals, still out on the loose, doing major damage? Where’s the justice there?”

Nye County’s attorneys have asked the federal judge to dismiss Evans’ lawsuit, arguing Boruchowitz is entitled to qualified immunity and Evans didn’t prove that county policy or systematic failures resulted in depriving her of her rights. County attorneys also filed a response to the lawsuit, denying that Boruchowitz and the sheriff’s office made a false arrest and violated Evans’ constitutional rights, adding police actions were justified.

Evans is now working in New Mexico at a job that pays less than half of her VEA CEO salary and with a lot less responsibility. “I’ve always tried to be, you know, the best person that I can be,” she said. “But my career, my reputation, everything was just trashed.”

Porn matinees

Years before the Evans case and lawsuit, Boruchowitz was tied to Pahrump-area scandals.

In 2013, two Nevada DPS investigators interviewed Boruchowitz after allegations surfaced that he had been showing videos of local adult residents having sex — and even sex with dogs — around the sheriff’s office, according to the Department of Public Safety report reviewed by the Review-Journal. The videos came from a residence where deputies were investigating child sex offenses.

In the DPS investigative report, Boruchowitz, then a detective, told investigators that he showed the videos to “a lot of people” not because they were evidence or part of an investigation, but for “coping” and “comedy relief.”

Boruchowitz’s “pornography matinees” were reported in the news. But the DPS report includes significant new details and Boruchowitz’s admissions to misconduct, revealed for the first time in this story.

DPS Sgt. Todd Ellithorpe asked Boruchowitz whether he would agree that “his actions were extremely unprofessional” and Boruchowitz responded that “it was not abnormal within the NCSO.” He told investigators that the street crimes unit widely showed “some gay rape locker room porn” around the station that they seized in a raid and one sergeant had an explicit photo of a person using a sex toy hung up at his desk.

Boruchowitz told investigators showing porn was “common practice” and the agency was “f——- up.” Under questioning, Boruchowitz conceded his behavior was unprofessional and probably not super respectful to Nye County residents, documents show.

But when Ellithorpe told Boruchowitz that in most law enforcement agencies around the country showing porn without an official purpose is a fireable offense, Boruchowitz responded that there “definitely is not anything in our policy about it.”

DPS declined to release the report, saying Boruchowitz’s privacy outweighed the public’s right to know.

Peeler, whose officers conducted the investigation, said state law only allowed his officers to investigate a case if called in by the agency, and then they had to let local officials and prosecutors deal with their findings. “Our hands were tied,” he said.

After the DPS probe, Boruchowitz was placed on administrative leave by Sheriff Anthony DeMeo, who died in 2019.

Boruchowitz’s porn matinees jeopardized the conviction of a sex offender. Jaysan Gal was found guilty of incest, lewdness with a minor, statutory rape and promoting sexual performance of a minor in 2018, and a judge sentenced him to life with the possibility of parole.

Last year, the Nevada Supreme Court ordered a new trial for Gal, in part, citing the failure of the trial judge to allow questioning about Boruchowitz’s bias after Gal sued him for showing sex tapes that included Gal. Gal’s current defense attorney did not respond to request for comment. The county settled Gal’s civil case against Boruchowitz for $35,000, records show.

Arabia was concerned about retrying the case a decade after the original investigation. “These cases can be very hard to prosecute even under ideal circumstances,” he said. “Now we face another trial and it’s going to be very difficult.”

FBI investigates misconduct

Boruchowitz was promoted to sergeant two years after the porn matinees investigation and two weeks after Wehrly took office. That same year, the FBI investigated allegations that he was having inappropriate relationships with criminals.

The FBI said they would not release the 2015 report because of privacy concerns. In a deposition, Wehrly confirmed the FBI probe but downplayed Boruchowitz’s actions.

“I can tell you that there was an FBI investigation into that, and at the conclusion of the FBI investigation, there was no crime and that discipline was what they would recommend,” she said. Boruchowitz testified that he received a 10-hour suspension for having an “inappropriate relationship” with a probationer.

No details of the misconduct allegations were included in the depositions, but the Review-Journal spoke to two former Nye County inmates who said they were interviewed by the FBI about Boruchowitz’s alleged misconduct. The Review-Journal granted them anonymity because the women feared for their safety.

One woman said Boruchowitz made lewd gestures and blew kisses at her while booking her on a theft charge. A second woman, who conceded she was a meth addict at the time but says she has since cleaned up her life, said Boruchowitz was trying to cultivate her as a confidential drug informant. She alleges he asked her to perform sex acts short of intercourse on him four times. She said she complied with his requests because she feared he might arrest her on drug charges.

Sheriff department policy prohibits officers from having personal relationships with people on parole or probation as well as detainees and people with felony charges. In 2018, Boruchowitz filed, but quickly dismissed, a federal court case alleging unknown individuals were falsely defaming and trying to get him fired over the FBI investigation. His attorneys wrote that the justice department declined to prosecute after the FBI turned the case over to them, court records show.

FBI spokeswoman Sandra Breault declined an interview.

In 2017, Boruchowitz was promoted to lieutenant and two years later to captain. His final promotion came about six months after he launched the controversial investigation of Evans and the VEA.

Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com and follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter. Kane is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.