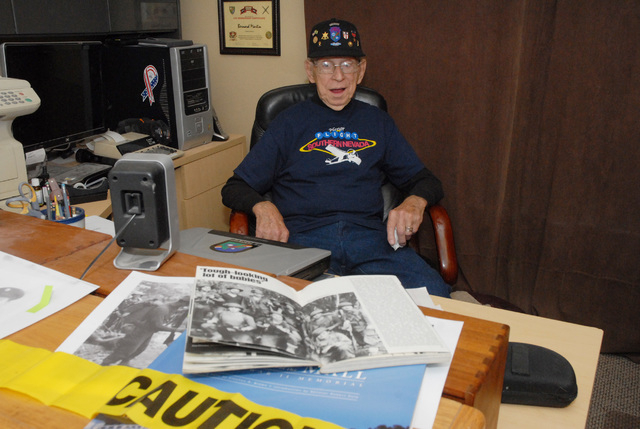

China to honor members of famed World War II unit

Bernard “Marty” Martin was already on assignment on New Georgia Island in the South Pacific during World War II as a radio operator when he heard a message the military was looking for volunteers for a very dangerous mission.

“I felt kind of stumped. There I was in the command car, sheltered, three meals a day and a place to sleep at night. Even though we were fighting I wanted to get more action. So I answered it the next day with my Social Security number. Next thing, two days later my captain came up to me and said, ‘what the hell are you doing volunteering without seeing me first?’ I said, ‘well I don’t know sir, it just came up because I wanted to get in the action.’ Well, he said, ‘your ass is out of here,’” the 92-year-old recalled.

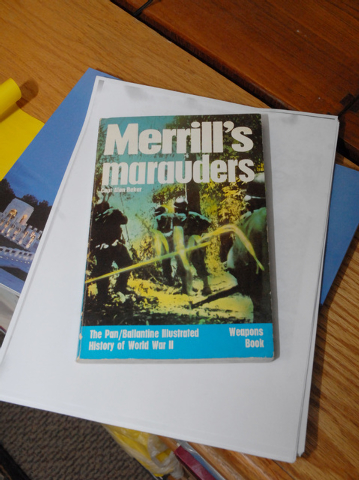

He ended up being a member of the famed Merrill’s Marauders, a unit that attacked Japanese troops camped out in the jungles of northern Burma in 1943. The warriors famously traveled 1,000 miles on foot in eight months during monsoon season, with only airdrops of supplies for relief. The unit was memorialized in a book, a movie, even a comic book.

Martin is the only surviving member of the third battalion. He was part of the Honor Flight of Southern Nevada that visited Washington, D.C. during the government shutdown last October. At the end of August, he will travel to Beijing, China on an all-expense paid trip funded by the Chinese government to attend the opening of the Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution. Martin said when Merrill’s Marauders cleared a village, the Chinese secured it and sealed it off.

A request has also been made to the Nevada governor and governors of other states to declare Aug. 10 as National World War II Merrill’s Marauder Day.

A Rhode Island native, Martin joined the National Guard out of high school and entered the Army’s 43rd signal company. He underwent training as a radio operator at Shelby Communications School in Mississippi. He also learned how to fire a machine gun.

His first assignment in New Georgia came after the Japanese bombed the radio operators and they had no communication, Martin said. After he signed up for what became known as Merrill’s Marauders — named after U.S. Army Brig. Gen. F.D. Merrill — he shipped out to Calcutta, India.

“I never saw such a ragged bunch of guys in my life, drunkards, I mean they were the spit of the service,” Martin said. “I found out after that everybody that had guys they didn’t want, they threw them in, they volunteered for them. Then you found out later those guys were the dregs of the service. Some of them were drinkers or guys that were going AWOL all the time or the ne’er do wells, but they all turned out top notch, thank God.”

The unit trained under British commandos in northern India for a few weeks before entering Burma.

“That’s when the unit started becoming cohesive. The guys who weren’t the best guys in the world started whigging up, we don’t behave and we don’t get started, we’re likely to end up in the grave. Everything started coming together,” Martin said.

Merrill’s Marauders numbered only 3,000 troops but they fought against 18,000 Japanese soldiers. They attacked about three dozen villages in teams where Japanese soldiers were living, then receding the next day.

“We couldn’t use the pass because if we used the pass the Japs would catch us. We had to chop every bit of the way. The Japs, they went crazy. How is it possible for a group to go from here to there in one day and night? It can’t be done,” Martin said.

“We were not a holding force, the Chinese were a holding force. They held everything,” he said.

Out of 30 skirmishes and five major battles, Martin recalls one in particular; it was the battle for a village called Walabum.

“There were 800 Japs in that village and it was a permanent, bivouac area. They had the radio shack up 100 feet in the air, made out of bamboo and they had barracks all the way around,” Martin said. “We stayed in the back at night and everybody starting unloading. We had mules, we used mules for carrying our burden.”

“Col. Beach, he was my colonel, he said this is going to be tough, we got 800 Japs to face,” he said.

They were only expected to observe, but got the message to attack.

“Then the next morning we were free to just blow the hell out of that village, which we did. I was down operating the radio and the bang of the noise was going like mad. After about two or three hours, my colonel called and said, ‘Marty bring your boys we’re going to need them,’” Martin said. “You don’t walk upright, you crawl because the bullets are flying all over the place and he said, ‘get down there and get that machine gun hot.’ He said, ‘you know how to operate a machine gun?’ I said yeah.”

The Japanese, who were confident they were almost invincible after conquering China at the war’s outset, walked right at Merrill’s Marauders instead of circling them from behind, he said. After they blew up the Japanese radio shack and most of the trucks and the barracks in the compound were on fire, a half-dozen Japanese soldiers emerged from the bottom of the hill where the marauders were stationed, according to Martin’s account. After a soldier on his one side was killed, Martin and another soldier gunned down the half-dozen Japanese. The remaining enemy soldiers who survived piled onto a few trucks still operating in the compound and drove away.

“When their commander said ‘Banzai,’ they ran right into them. They knew they were going to get killed and the river was just floating with bodies,” Martin said.

By the end of their eight months, about 200 Merrill’s Marauders were left alive out of the original 3,000, Martin said. The 2nd Battalion was caught on a hill and suffered about two-thirds casualties, he said.

When their tour ended, the unit cleared an airstrip that enabled another group, called Ma’s Task Force, to capture the town of Myitkyina in northern Burma, Martin said. The end of the Japanese occupation of Burma, a country now called Myanmar, was 90 percent complete, he said. He recalled some of the Japanese generals committed hari kari, a ritual suicide, in Myitkyina over their losses.

Martin still has an itchy, woolen shirt he wore among numerous mementos in his office study at home.

“My shoes would turn green and the leeches all over the place, you couldn’t sleep on the ground at nighttime, you’d wake up and they’d be on your eyes, they’d be on your nose, on your leg,” Martin said.

“We were fed by airplanes, C-47s would kick out the food on parachutes, the black would be ammo, the red would be medical, the white would be food,” he said. “A lot of times we had to chop trees down to give them a landing spot and they always liked it on a hill, so when they took off on a hill they got more speed.”

“I would say 90 percent of the time we got the food and a couple of times we went to get it and the Japs were up in trees — they learned that when parachutes were coming down there was food and they started killing our boys when they went to pick up the stuff.”

Martin ended up contracting what they called scrub typhus and was airlifted to a base hospital in India. He later was sent to Coral Gables Hospital in Miami. Martin took a liking to Florida and ended up building houses there, including a home in the Village of Golf for singer Bing Crosby and another for Burl Ives, he said.

No work would ever be as memorable as fighting alongside the men of Merrill’s Marauders, though.

In a letter after his reassignment to the Southeast Asia Command June 7, 1944, Brig. Gen. Merrill wrote to his troops: “All of you know what you have accomplished and I will not waste your time on this. However I want you to know that I feel that no other outfit in the United States Army could have accomplished the work which you have done.”