Failed solar project resurrected Old Spanish Trail’s forgotten past

Recent hearings over the BrightSource Energy solar project originally proposed on Tecopa Road just across the California state line included a history lesson about the days when pioneers traveled through on the Old Spanish Trail.

It was when travelers searched for the next water supply instead of the next gas station, when the Mexican government ran the Southwest. The route, from Santa Fe, N.M. to Los Angeles later became known as the Mormon Trail.

But the Old Spanish Trail Association said they’re just discovering lots more data about the historic route, which, though not as popularly, is also known as the California Trail in northern Nevada, where there is a new interpretive center west of Elko, the Santa Fe Trail or the Oregon Trail.

Clint Helton, a cultural resources specialist contracted by the California Energy Commission, concluded, “A segment does exist on the site but has been heavily impacted and has lost integrity,” Helton reported. It didn’t matter because BrightSource announced that after extensive permitting hearings it was suspending its project.

Natalie Lawson, representing BrightSource, said they identified a wagon road associated with the Old Spanish Trail that ran through their project site. She reviewed a combination of historic maps, journals, remote sensing and actual ground proofing.

But Lawson added, “The road is very well graded. It is used into the modern era. There is nothing of a historic nature of this road that remains and it is so impacted that the integrity of this road is such that it is not eligible for the California Register, nor is it eligible for the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing element to the overall Old Spanish Trail/Mormon Road.”

She said they did identify two other tracks, one a half mile north of the project and another known in literature as the Fremont Carson track, which is south of the project in the Charleston View subdivision.

Jack Pritchett, head of the Old Spanish Trail Association Tecopa Chapter, said the solar project would’ve severely impacted this section of the Old Spanish Trail, a mule trace from 1829 to 1848. The Old Spanish Trail Association is a nonprofit corporation that was formed in 1994. It is a citizen volunteer agency supporting the National Park Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

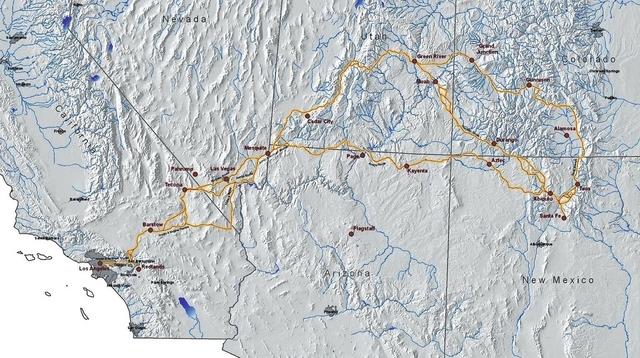

“This trail is more than 2,700 miles long and obviously the park service and the BLM can’t supervise active stewards for anything that long. So, at places along the trail, they have chapters of our organization that act as trail stewards, local representatives and so forth,” Pritchett told the California Energy Commission.

The organization has three members with doctorates on their national board, members include historians, archaeologists and local government officials that live along the route. He said members spend thousands of hours per year on trail research and surveys, in 2012 Pritchett said he spent more than 1,000 hours on trail research, preparation and report writing.

The Old Spanish Trail was in use between 1829 and 1848. There were more than a dozen different years the Mexicans sent caravans, so they didn’t always follow the same route, Pritchett said. Some years they would stop at Hidden Springs, sometimes at Stump Springs. The Mormon Road component of the trail was used from 1849 until roughly the 1880s, he said.

“There would have been scores and scores of wagon trails that would have stopped at these springs and then proceeded to the west,” Pritchett said. “We established that the Mormon Road certainly used campsites to the north.”

That was before Roland Wiley built an airport, a ranch and peach farm at Hidden Hills. Pritchett said flooding from rainy years, like 2005, can wash away the tracks.

Pritchett said his organization is looking into hiring a company to produce a 54-minute video with subtexts, featuring reenactments using actors to portray the trail, which he said was a major factor in the establishment of the economies of Southern California.

He said the Old Spanish National Historic Trail falls under the protection of the National Trail System Act of 1968. Congress designated the Old Spanish Trail in 2002; it runs through six states. He said the local chapter since 2007 has been working to trace, record and identify portions of the mule trace. They have been tracing the trail eastward from a point called Stump Springs, a not too reliable water source just cross the Nevada state line, to Emigrant Pass, near Tecopa, Calif.

At Emigrant Pass, members took Geographic Positioning System (GPS) recorders to take way points at a minimum every 25 meters, Pritchett said. He said it’s clear the trail extended from Stump Springs to Resting Springs. The pioneers used Stump Springs and Hidden Spring to the north and another water source farther to the north.

A semi-literate, French-speaking trapper named Choteau, during the period when the Southwest was under Mexican control from 1829 to 1848, advised Addison Pratt, who was about to embark on the trail, “if you don’t find water at Stump Springs then go to the north and you’ll find water at le parage,” he meant to say la perade or stop. If there’s no water there go up to “Le Rocher qui pleu,” identifying another water source in incorrect French.

“So it is very clear that, in 1848, it was known that, when you come down from the Spring Mountains and you arrive at Stump Springs, if there’s not water, you go north about four miles. And if you don’t find water there, you go farther north,” Pritchett told the committee.

Only about 15 miles of the 2,700 miles of the trail route are sign posted where the public is aware of it, can stop their car and visit the trail, Pritchett said. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. He said the trail ended at the central plaza in the city of Los Angeles, where it extended from Mission San Gabriel.

“If you go today and drive from Mission San Gabriel to downtown LA you will find no physical trace of the trail, but it’s on the congressionally-designated map. Not because there are physical traces, but because Congress said this is part of the route and it deserves historical recognition,” Pritchett told the CEC.

Historian Liz Warren produced a map drawn by respected cartographer Charles Preuss, a well-known map maker, who accompanied John C. Fremont on the trail in 1844, which was published in 1845. Fremont was ordered to survey and map portions of California, which the U.S. government at the time, was very interested in, she said. Fremont had five guides, only Kit Carson had been on a part of the trail.

Fremont was looking for the fabled San Buenaventura River, which was supposed to be something that would drain the huge, interior portion of the western U.S. Had he found it, the history of the region would’ve been different with river ports and barges, she said.

“They don’t find a thing. They find the Mojave River. They’re delighted when they find it,” Warren said.

After slaughtering three cattle, a young boy, Pablo Hernandez, and a man, Andres Fuentes, came into their campsite and told a terrible story about how the Paiutes attacked their horses and massacred their party down the road. At Bitter Springs, the Fremont party found everyone there was dead.

“So Fremont now is very far along on a route that he did not know about. This is a route that was used by the caravans and had been broken through, who knows how much earlier, it was in heavy use by that time and had indeed seen a tremendous amount of numbers of animals and people on it,” Warren said. “As a matter of fact, that’s the part of the route that was used earlier, in 1840, by the horse raiders who would come in off the Great Basin, accompanied by Wakara, the Ute chieftain, and other Native Americans, as well as mountain men and fur trappers and all kinds of people to raid the California ranches.”

The number of horses herded west changed the California economy at the time, Warren said.

In the desert, traces and trails go between water sources, as long as there’s not an obstacle, like the stretch between Stump Springs and Resting Springs, the trail will go in a straight line, Pritchett told the CEC. But Warren differed, she described a wandering route as animals went through to find water sources.

Geoffrey Spaulding, an expert hired by BrightSource Energy, in arguing against the historical value, said, “the direction of the trail across this valley, has, essentially, no predictive value with respect to where the trail will lie in the Pahrump Valley.

“What will happen is that there’ll be folks traveling either east or west in this general area, they’ll cross a pass, and then a decision will be made.”