Mona Bell’s grave a Rhyolite tale born of legend

Editor’s note: This is the second part of a two-part article about a legend in the ghost town of Rhyolite. The first part ran in the Oct. 28 edition.

So what did happen to the earthly remains of Mona Bell?

After the brawl in the cabin ended with the gunshots that took Mona’s life in January 1908, Fred Skinner went running down the Rhyolite street in his union jack underwear, yelling that he wanted to make a confession. He was intercepted almost immediately by a patrolman who sent several other officers to the cabin to investigate.

In a trunk by the bed near where Mona’s body lay, the police found a bundle of letters and photographs carefully saved by the young woman. Among them was a letter from her mother that Mona had been carrying from one mining camp to another, so far from home.

So many worlds away that Carrie Peterman of Ballard, Washington, no longer knew where to find her own ‘dear daughter.’ Not until she got the telegram from Rhyolite with the grim news of the murder.

Mona Bell, it turned out, had been born Sarah ‘Sadie’ Isabelle Peterman in 1887. On the night she died she was only 20 years old and still legally the wife of another man.

Clinton Columbus Heskett had eloped with Sadie to Colorado when she was just 18 and they’d been married less than a year when Fred Skinner whisked her off to Nevada. Heskett had been searching for her ever since.

Heskett arrived in Rhyolite within a few days of the murder, gave his statement to the police and collected the battered body of his once lovely young wife. He escorted her back to her family in Ballard, where Sadie Heskett was buried at the Crown Hill Cemetery in a plot hastily purchased by her father.

After a quiet funeral service and without even placing a marker on her grave, the family got on with their lives, preferring not to think too much about their lost and wayward girl.

After that, Sadie Isabelle was mostly forgotten, except when Skinner came up for parole and the family dutifully wrote, each time they were asked, that they believed he had paid his debt to society and should go free.

In the mid-1980s, an aged niece of Sadie Heskett paid to have a small, plain headstone placed on the grave.

Mona legend born

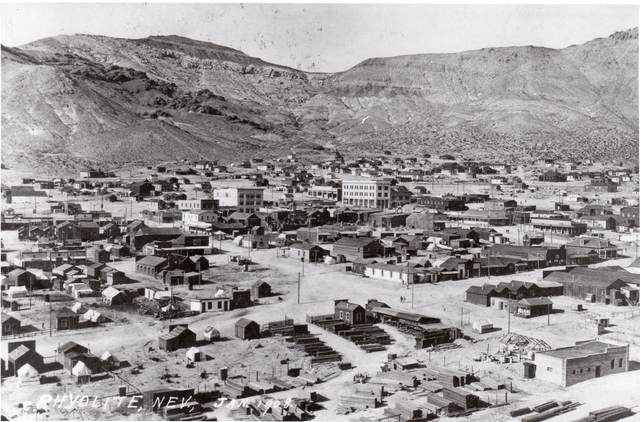

Back in Nevada, as Rhyolite declined, its few inhabitants became more eccentric and colorful. In the 1930s a man named Norman Westmoreland opened a gambling hall called the Ghost Casino in the old train depot. When he died in 1947, his sister Frederica inherited the property. In 1953 she finally convinced her retired minister husband to move to the old ghost town and they turned the erstwhile casino into a museum and curio shop.

Frederica Heisler loved Rhyolite and its history, though most of what she knew she learned from the legends handed down by old-timers who came back to reminisce. Sometimes, they mentioned the awful murder of Mona Bell, and Mrs. Heisler, who knew a good story when she heard one, told the story to the tourists, who appreciated the pathos and drama.

Some 40 years later, when Suzy and Riley McCoy came to Rhyolite to begin a long tenure as its resident caretakers for the BLM, the story had been handed down from one guardian of the ghost city to another and had stretched a bit in the process.

The most noticeable difference being that some time in the 1950s, Mrs. Heisler erected a small grave with a wire fence and a wooden cross out by the old jailhouse and began telling her visitors that’s where Mona Bell was buried.

The McCoys went on to conduct a historic resource survey of Rhyolite on behalf of the BLM and came to know its history in extraordinary detail.

But they also respected its traditions, and as all the caretakers before them had done, they carried on Mrs. Heisler’s legacy, embellishing the story for visitors.

“But we would always ask,” Suzy McCoy says, “do you want the truth, or do you want the legend?”

Almost always, people would choose the legend.

So the McCoys would tell it something like this: Mona Bell was a young prostitute who’d been killed by her pimp. The respectable women of Rhyolite refused to allow her to be buried in the proper cemetery and so the miners, who loved her and grieved for her, dug this lonely grave out on the edge of town behind the red-light district. Before they consigned her to the earth, they carried her through the streets in a parade.

A synthesis of several true Old West stories about prostitute funerals, the legend rarely failed to affect the visitors who heard it and they began to leave little trinkets on the grave. For several years, a group of artists and actresses met in Rhyolite every fall, gathering at Mona’s grave as part of a larger celebration of wildness and creativity.

Pahrump’s Red Hats adopt Mona

Then, in late 2010, the Garden Mistresses Chapter of the Red Hat Society out of Pahrump visited Rhyolite on one of their outings. The chapter’s then queen, Jeanie Geiser, was touched by the story of Mona Bell and by the pitiful condition of the grave, so much that it stayed with her long after she returned home.

She called a meeting of the Garden Mistresses and all of the women who’d been there, and who shared Geiser’s feeling of empathy and protectiveness, decided to adopt Mona Bell and to look after her in the only way they could. They would clean and repair and decorate her grave so that her memory would not disappear the way so many of the other earthly remains of the town were crumbling to dust.

Because they weren’t sure who to ask or whether they’d be given permission, the Red Hats decided that theirs would be a clandestine mission of goodwill, Geiser recalls, and they swore each other to secrecy. A friend of the group fabricated a metal cross and painted it with Mona Bell’s name, both her work name and the closest approximation they could find to her real name. Another friend donated a roll of wire fencing and some wooden posts.

Sometime in early 2011, the Mistresses loaded up their vehicles and made the trip to Rhyolite, where they cleaned and brought order to Mona Bell’s grave. When they were done, said Geiser, “We had champagne and we toasted her and poured a glass on her grave. It was like she was right there with us.”

The Garden Mistresses chapter of the Red Hats is disbanded now, but its members still try to get out to Rhyolite when they can to check up on the grave. They laugh about their clandestine mission, but their determination to honor the memory of an abandoned young woman who suffered such abuse in her lifetime is still a source of pride to them all.

Red Hats Jeanie Geiser and later Queen Helene Campton both say they felt a kinship between Mona Bell, the adventuress who paid so high a price, and their group. “We are fun-loving, outspoken, adventurous women,” Campton says. “There’s a bond there.”

That Sadie Heskett’s actual remains were buried elsewhere was really beside the point. “There is something there,” says Geiser. Perhaps it’s something on the wind or in the dust, but there’s something people feel when they visit Mona Bell’s grave.

Suzy McCoy agrees.

“I don’t know if I believe in ghosts,” she says, “but if Mona’s out there, she’s having lots of fun.”

The body of Sadie Heskett may be buried in Ballard, Washington, but the spirit of Mona Bell lives on in Rhyolite.

Robin Flinchum is a freelance writer and editor living in Tecopa, California. Her book, “Red Light Women of Death Valley,” was published last year.