The legend of the Rhyolite grave of Mona Bell

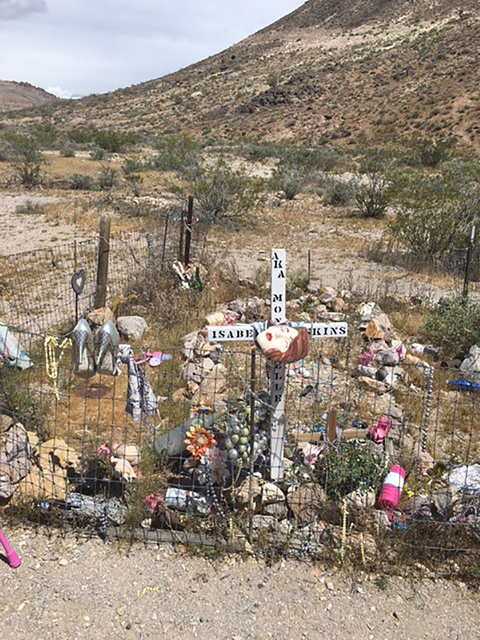

East of what was once a busy red-light district and south of the ruins of the old jailhouse in the ghost town of Rhyolite, lies a grave enclosed by a fragile fence festooned with Mardi Gras beads and high heel shoes. Alone in the sagebrush and debris of the past, the little grave is marked with a painted cross bearing the name Mona Bell.

In 1908, when Mona Bell lived and died in Rhyolite, there were as many as 6,000 citizens in what was then a thriving mining community. In the busy shops on the streets, the noise of the mines, the clatter of the wagons and clamor of brand new automobiles, Rhyolite was all promise and motion.

Today, tourists wander among its ruins awed by the silence and stillness and by the way in which a city could appear and then disappear in only a few short years. Sooner or later, according to caretaker Karl Olson, who watches over the wind-swept remains on behalf of the Bureau of Land Management, most of those visitors find their way to Mona Bell’s grave.

In Olson’s estimation, it’s the most visited spot in Rhyolite today.

Some stumble across it by accident. Others, those who know the legend, seek it out—sometimes to pay tribute, sometimes to cast a protective eye over it and neaten things up. Some visitors come at night, under the light of the full moon, to dance and make merry and to celebrate the spirit of all wild women in the name of Mona Bell. They leave tokens—bottles of whiskey, cigarettes, casino chips, dolls—and take photographs.

Before the spirit of Mona Bell captured the imagination of modern-day desert pilgrims, the flesh-and-blood woman earned her living here as a prostitute, dance hall girl, and saloon keeper in the town’s rowdy red-light district. She died here not far from where the grave now stands.

In the pre-dawn hours of January 3, 1908, in a shabby little adobe cabin on Rhyolite’s Main Street, policemen found the body of 20-year-old Mona Bell in a white nightgown on her knees beside her bed, as if in prayer. The deliverance she sought was not divine, however, but rather a .38 revolver on a shelf above her head.

She’d been reaching for it when her boyfriend, a gambler and wastrel who called himself Fred Skinner, shot her three times from behind. One bullet pierced the heart, killing her instantly, and she dropped to her knees, propped up by the bed frame. In that upright position, her life’s blood flowed from the wounds, saturating her night dress and streaming in rivulets across the floor.

That same morning, Fred Skinner (whose real name was Llewellyn Felker) gave himself up and was lodged in the Rhyolite jail. Today one wall of the old jail— a squat, boxy little fortress— still holds the shape of its windows. Through these portals now the grave is clearly visible, a festive anomaly in the muted desert landscape. But in 1908, if Skinner had been allowed to look out of the window, all he would have seen was an angry, muttering mob of citizens collecting outside, threatening to go for a rope to hang him.

The men of the town objected not only to the murder of a pretty young woman by a brute and a wastrel who had lived off her earnings but to all the vagrants and pimps who inhabited the red-light district and brought trouble with them as sure as the rain brought mud.

Behind them, in the distance, Skinner might have caught a glimpse of the Adobe Dance Hall on the corner, where Mona worked when she first came to Rhyolite.

At the Adobe she’d saved up enough money to go in halves with another dance hall girl and buy the canvas saloon located next door. On New Year’s Day, the two women opened the doors of the Mission Bar. The next night Skinner became drunk and belligerent, fighting with Mona, smashing up the bar and pounding her with his fists until she seemed to wilt into submission and asked for permission to go home.

Later Skinner would claim that when he returned to their cabin that night, he told her he was going to leave her and go back to his wife in Colorado.

He said Mona was drunk and had flown into a jealous rage. She had grabbed one of the many guns he kept in the cabin and shot him twice, the bullets glancing off his rib cage and breast bone. He’d wrestled the first gun away from her and she’d run toward the shelf to try again. She meant to kill him, he said, so that no other woman could have him. He’d been forced to kill her to save his own life.

Since Mona Bell, now cold on a slab at the funeral parlor, could not defend herself against Skinner’s accusations, Rhyolite undertaker Otto Bacigalupi did his best to speak for her. He could read the story of her relationship with Skinner in the bruises and lacerations he found on her face, her hands, her arms and her legs. He told of the beatings she must have endured, not just that night but on previous nights and who knew for how long before that.

A miner named Byon Demmings, who had been at the Mission Bar with Mona and Fred that last night confirmed what Bacigalupi suspected. Skinner had beaten Mona Bell mercilessly in front of her friends, Demmings testified. When Demmings suggested Skinner should not be so rough on the girl, he said, “F—- her, she’s used to that.”

But Mona Bell and Fred Skinner had only been together for about eight months—not long enough for a young, lively, intelligent woman to truly become used to living under the hammering fists of an unpredictable man. That night, battered, drunk and desperate, she had apparently decided to fight back, even if it cost her her life.

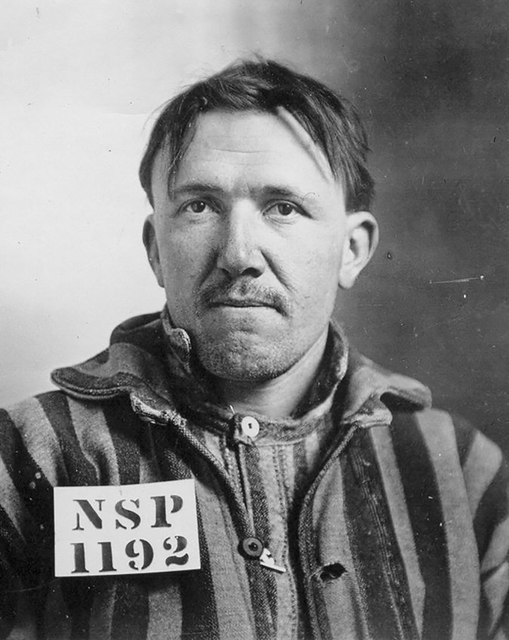

Skinner was eventually tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. On appeal in 1910, his sentence was reduced to 50 years.

Not counting a couple of prison escapes and a doomed parole stint, he served a total of 23.

Skinner was released from the Nevada State Prison in 1931 and would soon resurface in Las Vegas, where he became a Prohibition Era bootlegger under the alias Doc Russell.

Rhyolite as he had known it was all but gone by then. If Skinner had stopped there on his way through Nevada, he might have marveled at the quiet and stillness of the place. Perhaps he’d even have gone to the little grave by the jail to pay his respects.

Except that the little grave did not yet exist. In fact, it would not appear on the abandoned landscape for another 20-some years.

So what did happen to the earthly remains of Mona Bell, and who planted the cross on that little grave in Rhyolite? Learn the answers in Part Two next Friday.

Robin Flinchum is a freelance writer and editor living in Tecopa, California. Her book, “Red Light Women of Death Valley,” was published last year.