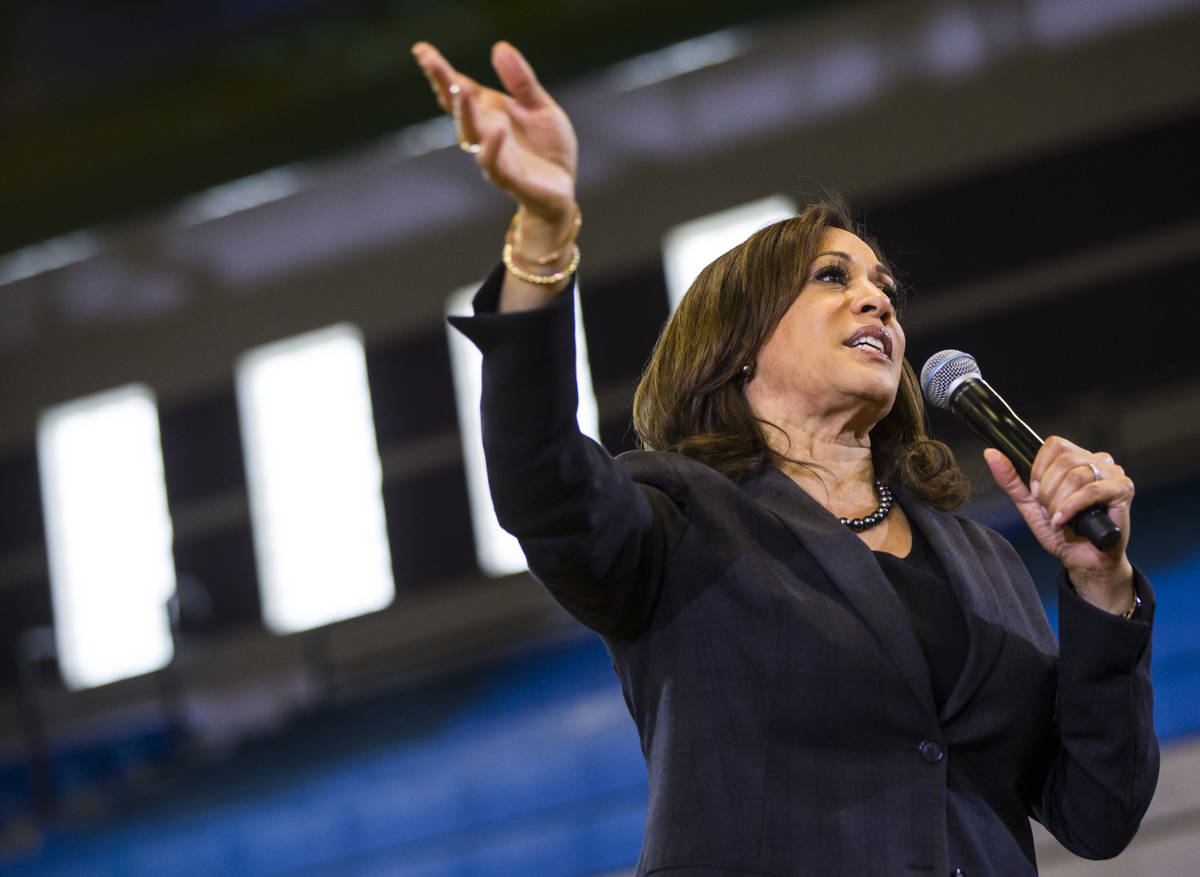

DEBRA J. SAUNDERS: Kamala Harris: progressive opportunist

When former Vice President Joe Biden announced that Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., would be his running mate, a New York Times tweet labeled Harris “a pragmatic moderate.” As someone who covered her when she was a San Francisco prosecutor and California attorney general, I’d say a more apt description is “progressive opportunist.”

Two controversies define her career.

First, there’s her support for San Francisco’s sanctuary city policy, which began in the 1980s as a means to reassure undocumented immigrants that they could report crimes to the police without fear of deportation. During a Democratic primary debate in June 2019, Harris explained her opposition to President Barack Obama’s Secure Communities program, which required local law enforcement to share fingerprints with federal immigration authorities — which San Francisco and Sacramento actively resisted. “I know it as a prosecutor. I want a rape victim to be able to run in the middle of — to run in the middle of the street and wave down a police officer and report the crime against her,” Harris said.

Sounds reasonable. Who doesn’t want a rape victim to be able to report a rape? But over time, the City by the Bay and California pols interpreted and rewrote ordinances so that they protected violent and repeat offenders in the country illegally.

Harris was a leader in the stampede. Even when it was shown that the sanctuary laws protected dangerous individuals, City Hall would not fix its unsafe sanctuary city policy out of the apparent belief that people in the country illegally have a right to break a host of other laws.

Beneficiaries of the policy included Edwin Ramos, who was convicted for the 2008 fatal shooting of San Franciscan Tony Bologna, 48, and his two sons, Michael, 20, and Matthew, 16.

In 2003, a teenage Ramos assaulted a man on a bus — for which he was convicted. San Francisco did not notify immigration authorities. City law enforcement also did not contact federal immigration officials after Ramos was convicted for trying to rob a pregnant woman and her brother, a felony. Harris did not prosecute Ramos, by then a twice-convicted felon, after he was stopped by police in a car without plates and illegally tinted windows and one of those fleeing tried to ditch a gun later tied to a double murder.

Is it Harris’ fault that Ramos killed an innocent father and his two sons? Absolutely not. But she should be recognized as a civic leader who didn’t think it was her job to do something about undocumented immigrants who threatened public safety.

When it was reported that she had an undocumented immigrant who pleaded guilty to a drug felony enrolled in her signature Back on Track job training program — even though it wasn’t legal for him to work — Harris told the San Francisco Chronicle it was a design flaw. But she didn’t check to see if other undocumented immigrants, who could not work legally, were enrolled in the program.

Harris did not ask for the death penalty for Ramos, who was convicted for the three murders. She also refused to seek the death penalty against the shooter who later was found guilty in the shooting death of San Francisco police officer Isaac Espinoza. She explained that she had voiced her opposition to capital punishment as she ran to be San Francisco district attorney, so she was keeping faith with her beliefs.

Harris’ supporters defended the decision as proof that the Democratic prosecutor would not turn her back on her principles.

Problem: She ditched that core value when she decided to run for attorney general in a pro-death penalty state. With her political career at stake, Harris assured voters that she would uphold capital punishment because it was the law.

Indeed, in 2014, Harris defended the death penalty in court after a federal judge ruled that the state’s capital punishment law was unconstitutional because it was too arbitrary and riddled with delays.

But later, when families of murder victims went to court to institute a one-drug lethal injection protocol in California that could win approval in the U.S. Supreme Court and put San Quentin’s death row back in business, Harris tried to block the suit on the grounds that the families lacked “standing.” That’s legalese for: Their beliefs didn’t count.

It tells you something about Harris’ legal skills that the aggrieved families, individuals so unenlightened as to want California to impose capital punishment, beat her in court, with an assist from Sacramento’s Criminal Justice Legal Foundation.

Another black mark on Harris’ career involved a cocaine-skimming scandal in the city’s crime lab in 2010.

Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo wrote that the failure of Harris and her office “to produce information actually in its possession regarding” a retired technician’s unreliability was “a violation of the defendants’ constitutional rights.” And still Harris ran for attorney general.

Harris wasn’t a hard-core district attorney, and she wasn’t a tough-on-crime attorney general. But that didn’t stop her from getting on the Democratic ticket.