VICTOR JOECKS: Eviction moratoriums latest example of compassion producing bad public policy

If you’re looking for a spouse or a friend, compassion is a highly desirable characteristic. But in politics, being “compassionate” — with someone else’s money — often produces flawed public policy.

Consider the purpose of government.

The most famous phrase from the Declaration of Independence declares the Founders’ belief that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

What’s less well-known, but just as important, is the next phrase: “That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men.”

Elected officials who make the laws, then, have an obligation to uphold those rights. At a minimum, they should reject a law or regulation if it would infringe on a person’s rights.

Note that these rights allow people of different religions, races, political beliefs and incomes to coexist. You can pursue happiness in your own way — by … say, owning property. Buying property in a mutually agreed to transaction doesn’t take away someone else’s rights.

To ensure these rights, citizens give government immense power. If your neighbor robs you, you can’t imprison him in your spare bedroom. The government sends him to jail. You can’t take money out of someone’s paycheck without permission. The government does.

Both the federal and Nevada state constitutions recognize the inherent dangers that come with this power. To prevent tyranny, these foundational documents put key protections in place. These include civilian control of the military and separating power among three branches of government.

Those measures aren’t perfect. Slavery and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II are but two examples of instances in which the U.S. government violated people’s rights.

It’s this immense power that makes misguided compassion among elected officials concerning.

Imagine a friend loses his job and can’t make his mortgage payment. You could personally offer him financial support. You could find him a place to stay or even offer a room at your home. You could direct him to a church, synagogue or nonprofit that assists people in such circumstances.

What you couldn’t do is move him into your neighbor’s house without obtaining your neighbor’s permission. It doesn’t matter if your neighbor’s home has four spare bedrooms or if your neighbor owns 10 other houses. Your compassion for your friend’s situation doesn’t supersede your neighbor’s property rights.

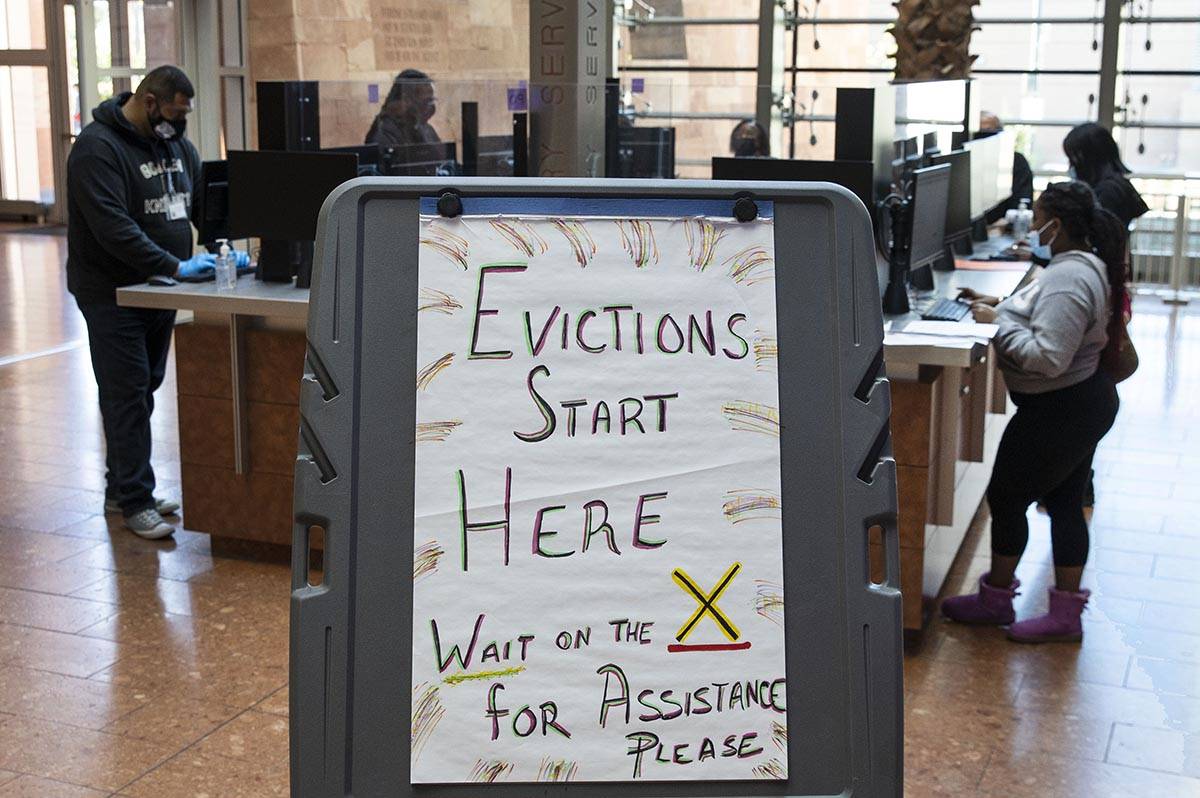

But the above scenario is equivalent to what federal and state politicians have done to landlords over the past few months. Perhaps the unknowns of the virus and overwhelmed unemployment systems justified an eviction moratorium during the early stages of the pandemic. But we’ve been past that stage for many months. The CDC’s moratorium ended Saturday, and President Joe Biden has called on Congress to extend it.

The prolonged eviction ban is an example of misplaced compassion. Politicians — including Biden, former President Donald Trump and Gov. Steve Sisolak — were concerned about those facing eviction. That’s an understandable emotion, but it doesn’t excuse taking someone else’s property.

Once you understand this idea, you can see how false compassion worms its way into many policy issues. Politicians want people to earn more, so they force employers to hike their wages.

Politicians sympathize with illegal immigrants who want to come to America. So they welcome them into the country illegally, ignoring the low-income Americans who are hurt by increased competition in the labor market.

True compassion means giving your own time and resources — not somebody else’s — to help someone.

Contact Victor Joecks at vjoecks@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4698. Follow @victorjoecks on Twitter.