Preparing for an uncertain renewable energy future in Amargosa Basin

In late 2024, decisions made in Washington were moving faster than desert communities could respond. In the Amargosa River Basin, ninety minutes west of Las Vegas, the future of land, water, and small rural towns felt suddenly up for negotiation. The outgoing Biden administration was rushing to finalize the Western Solar Plan, a framework that could shape renewable energy development across the West for decades. In Nevada’s Amargosa Basin, about ninety minutes west of Las Vegas, communities and conservation groups were struggling to keep pace.

More than two dozen large solar proposals were advancing at once, mostly on public lands in a sensitive desert landscape. Local leaders worried about losing open space near homes, schools, and small businesses, while projects could cause impacts to air quality and land values. Conservation groups grimly reviewed maps showing projects pressing up against places like Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. Also at stake was the water that makes the Amargosa Basin such a special place: dozens of projects would consume billions of gallons of water during construction, potentially affecting the aquifer that sustains both the communities and the ecosystems there.

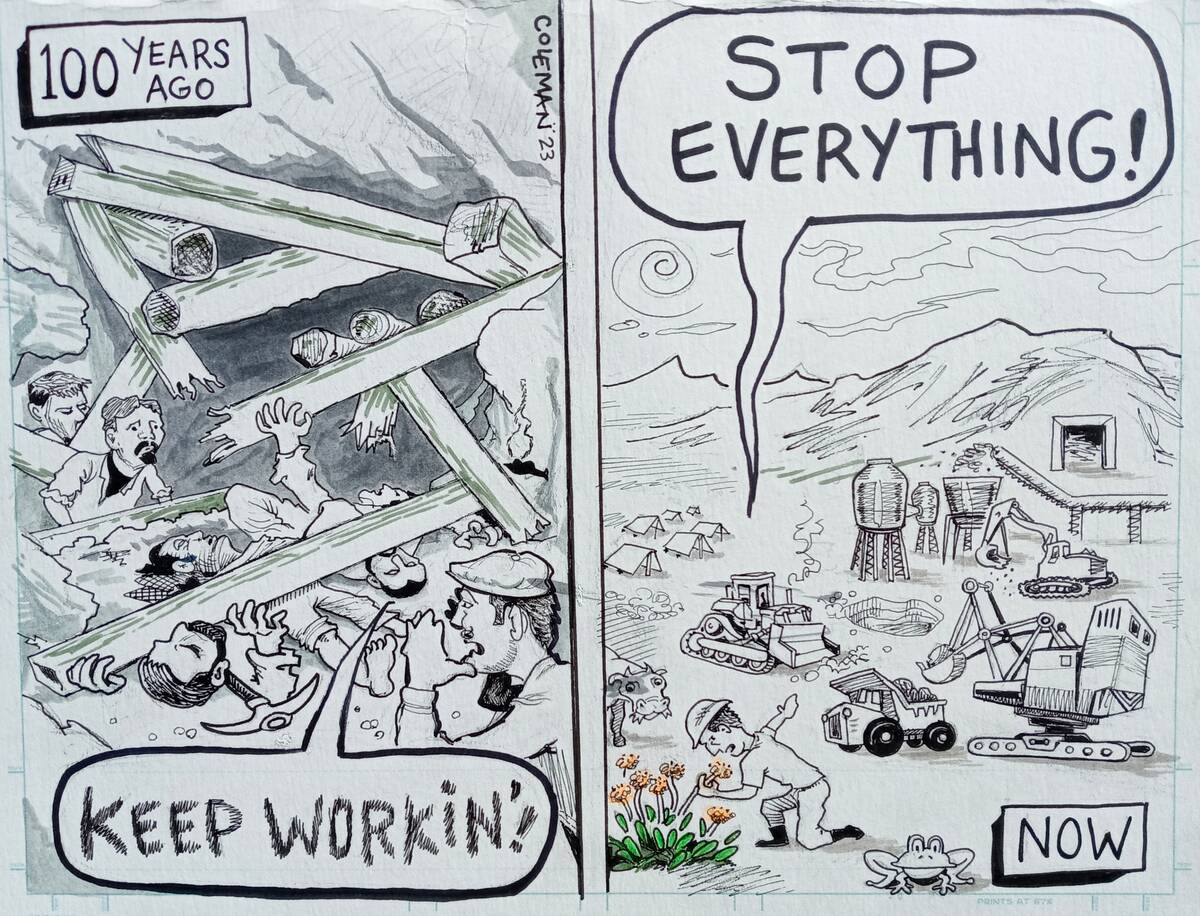

The pace and scale of the proposed solar developments, and their potential consequences, left many in the Amargosa Basin feeling overwhelmed.

A year later, much has changed, and much has not. Under the new administration, renewable energy has taken a back seat to other priorities, including mineral extraction. Financial incentives that once drove rapid solar development have weakened. Many companies have shifted from public lands to private land deals, partly to avoid new permitting challenges. Political priorities continue to shift, and communities with deep ties to places like the Amargosa Basin are left unsure what comes next.

As executive director of the Amargosa Conservancy, I hear this uncertainty often from Tribal leaders and rural residents. Some describe this moment as a pause after years of stress over solar energy proposals that felt rushed and poorly sited. Others worry that if national priorities swing back again, development pressures could return just as quickly.

Across these conversations, the same questions come up: what does a balanced approach to renewable energy look like here, and how do we protect what matters most?

A responsible and fair energy transition depends on careful, inclusive planning. California’s Desert Renewable Energy and Conservation Plan (DREPC) offers a useful example. Through collaboration among agencies, Tribes, local governments, environmental groups and industry, the plan identified where large-scale solar development in the California Desert made sense and where it did not. It allocated hundreds of thousands of acres for development while setting aside millions of acres for conservation, including most of the California side of the Amargosa Basin.

More than a decade later, many, though not all, communities involved in the process ultimately gained certainty in the rollout of solar energy that helped preserve their quality of life. Developers also benefited from clearer expectations and fewer conflicts. The process was slow and complex, but it produced results that many consider a success.

Unfortunately, the Western Solar Plan was nothing like the DRECP. It allocated millions of acres for solar while setting aside nothing for conservation or preservation of rural communities’ ways of life. It was a giveaway to industry and hung the environment and people out to dry. Places like the Amargosa Basin need new planning efforts which more properly balance considerations of industry, communities, and the environment.

Beyond better planning, communities like those in the Amargosa Basin need stronger commitments from developers to act as good neighbors. That means paying attention to local quality of life, supporting local businesses, and ensuring that public services can keep up with growth. It also means protecting long-term water security and conserving plants and wildlife that make this region distinct.

This can be achieved through pursuing Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs): legally binding contracts between developers and communities for investments in infrastructure, conservation, and community needs to offset impacts from proposed projects. Executing effective CBAs in response to the communities’ expressed needs and values will be critical to ensuring renewable energy development in this special region is done fairly and sustainably.

One key element that made the DRECP succeed is that development was accompanied by land conservation. Vast landscapes were preserved forever, to compensate the desert for what was being lost to energy production. A similar approach is needed in the Amargosa River Basin. There is a proposal on the table from the Biden administration to withdraw over a quarter million acres surrounding Ash Meadows and the community of Amargosa Valley from mining, but it has not been finalized. This action (or an even more comprehensive protective measure) is an essential piece of the balance needed in the Amargosa River Basin.

None of this will be simple or happen quickly. But if renewable energy is to become interwoven into the future of landscapes like ours, no shortcuts or end runs can be taken, and there is no time to waste. Our communities, our water, our economies, and our children’s inheritance are at stake.

Mason Voehl is executive director of Amargosa Conservancy, a nonprofit organization working toward a sustainable future for the Amargosa River watershed through science, stewardship and advocacy.