In bygone era, federal government once operated Tonopah brothel

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of stories by historian Bob McCracken on the history of prostitution in Nevada and Nye County. A new feature in the series will come out every Friday for the next several weeks.

Nevada became a state in 1864, largely as a result of economic activity triggered by the discovery of an enormous deposit of silver at Mount Davidson near present-day Virginia City.

Those who arrived too late to cash in on the Comstock, as the deposit was known, headed into the wilderness in their quest for valuable minerals. Other discoveries soon followed at such places as Austin, Aurora and Eureka. Boom towns based on mining were sprouting like flowers on the desert floor.

But after about 1880, the fortunes of mining in Nevada went into decline.

Formerly vibrant Nye County communities such as Ione, Belmont, Tybo, and Reveille either disappeared or became shadows of what they had been.

Then in 1900, Belle and Jim Butler discovered a huge deposit of silver at what became Tonopah.

As with the Comstock, the Butlers’ discovery was quickly followed by prospectors finding precious minerals at Goldfield (1902), Rhyolite (1904), Manhattan (1905), and Round Mountain (1906), among others.

The town of Johnnie in southern Nye County dates to 1905.

This boom period, with all its vibrant can-do spirit and optimism for the future, was the last full flowering of the old West in America.

Prostitution was an important part of life in all frontier mining communities.

Large numbers of young unattached males seeking their fortunes guaranteed the presence of significant numbers of women who delighted in helping these men have a good time and spend their money.

Thus came the bars and brothels where the men and women could meet and enjoy what each other had to offer. At first, there were typically no restrictions on where such “meeting places” could be located in a growing community.

Very soon, however, it was realized that these establishments needed to be restricted to one or more selected areas of town. The last thing a tired worker needed was to be kept awake all night with the goings-on at a brothel next door to where he was living; or, as more families moved to the new town, having wives and children exposed to this raw aspect of community life.

Most people supported the existence of prostitution but thought it needed to be confined to a red-light district. Early on, Tonopah had two red-light districts. One was located on St. Patrick and Central streets between Oddie and Brougher avenues, approximately behind where the L&L Motel sits today. The other was along Corona Avenue north of where the old Campbell &Kelly garage now sits.

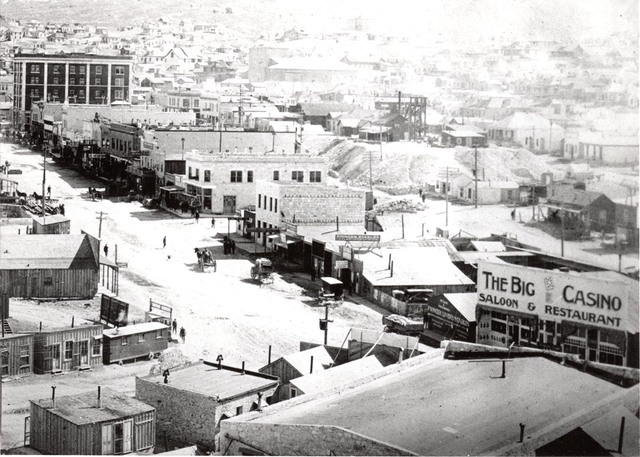

The Big Casino

The Big Casino, known initially as the Casino, was the entertainment hot spot in Tonopah for more than 15 years. It was located on Main Street in the same block that fronted on St. Patrick Street, one of the two flourishing red-light districts. Business at the casino was so good that, in January 1909, it was incorporated as the Big Casino Company.

The Big Casino opened in late 1904 or early 1905 as a restaurant, saloon, betting parlor, dance hall, and hurdy-gurdy house. It claimed to be “the biggest of its kind in the world.”

By 1907, the establishment featured direct wires to all major racetracks in the country and provided patrons the opportunity to bet on all important sporting events. It was involved in the promotion of sporting events and, with other groups and businesses, sponsored the Gans-Herman World Lightweight Championship fight on New Year’s Day 1907 held at the newly constructed Big Casino Athletic Club.

A rarity for a frontier mining town, the Big Casino employed a small orchestra. The music of Jules Goldsmith and his musicians could be heard there and the orchestra was sometimes hired by “uptown residents” for their “respectable social events.”

The Big Casino was well known throughout central Nevada; men traveled there from miles around to drink, dance, gamble, and have a good time. The Big Casino did well financially until Oct. 1, 1910, when Nevada’s anti-gambling law went into effect.

Although enforcement of the law was sporadic in Tonopah as well as in Nevada generally, the Big Casino suffered economically. In 1913 it found itself in federal court as a litigant with financial troubles. On Aug. 20, Judge W. W. Morrow of the U.S. Circuit Court at Carson City appointed Frank P. Bonneau as receiver for the Big Casino Company until financial matters were straightened out.

With rumors that the establishment would be shut down with the federal takeover, Bonneau quickly announced that business would continue as usual.

Thus, the federal government found itself in the odd position of operating a hurdy-gurdy house in Tonopah.

There were 25 to 30 women employed at the Big Casino and the government paid them 40 percent of all drinks they sold and 50 percent of all receipts for dances and other activities.

At that time there was a strong socialist movement in Tonopah.

In late October of 1913, a correspondent for the International Socialist Review, a national publication of the Socialist Party, arrived in town to report on local Socialist activities.

The correspondent was also interested in taking a look at the strange relationship that had evolved between a hurdy-gurdy house and the federal government. By coincidence, the Socialist correspondent arrived in town on the same train as the receiver for the Big Casino and “three new chickens for the dance hall.”

In the meantime the Big Casino was sometimes referred to as “Woodrow Wilson’s Dancing Academy.”

Woodrow Wilson, of course, was president of the United States at that time. When the Socialist correspondent became aware of the identity of her fellow passengers she took it upon herself to interview the women. When she asked one of them how she liked her new boss, that is to say President Wilson, the dancer replied confidently, “I should worry! I’m working for the government.”

As it turned out, she should have worried. On Nov. 12, 1913, Nye County commissioners revoked the Big Casino’s liquor license for violating the state’s anti-gambling act. It seems the state legislature had passed a law in the previous session that commissioners act as a liquor board.

Nye County commissioners ruled the operation of the Big Casino a “public nuisance” and “detrimental to the peace and morals of the community.”

The place never returned to its previous vigor. By 1920 the dancehall had been abandoned and the place was converted into the Big Casino Hotel. (It was still a brothel.)

On Aug. 23, 1922, in what the Tonopah Daily Bonanza stated was “the worst conflagration in the history of Tonopah,” much of the town’s lower end, including the casino building and most of the brothels in the red-light district, were destroyed by a terrible fire (The Valley News, July 13, 1977).

Joe Andre and the Big Casino

Joe Andre worked as a musician at the Big Casino from April 1, 1921, until it burned down.

Years later, he recalled that the Big Casino “had the biggest band in town.” He said there were three or four other dance halls in town but they had only a couple of musicians working in each.

Joe described the Big Casino as “a beautiful place.”

When you entered from the front, the first thing you came to were three gambling tables and a bar. There was a big maple dance floor with an oak railing between the bar and the dance floor.

At the far end of the dance floor was the bandstand, built like a theater stage. One side of the dance floor was lined with booths, and each had a table and chairs inside and a door that could be closed. This is where the girls took the fellows to have a drink.

Around the top of the dance floor was a balcony with a row of rooms with beds, which made it the largest sporting house in Tonopah. Joe said there were a number of other “houses” in the neighborhood. He said some of those joints had one girl, others two or three, but there were a dozen girls working as prostitutes at the Big Casino.

He said they usually hung around the bar. “A customer would come in and buy them a drink. They would either drink at the bar or go to one of the boxes.”

Drinks were 50 cents and the girls got half. All the girls’ drinks consisted of “colored caramel water.”

The girls tried to get the men to dance with them before buying a drink. A dance cost $1 to $10, Joe recalled, “depending on how much the fellow liked her and the more he liked her, the more she charged.”

In order to maximize profits, Joe said, “We played short numbers… . Some of the girls couldn’t even dance. They would just wobble around the floor.”

He said the women dressed in various types of attire. Some wore fancy clothes, others “just regular clothes.”

Most, however, were “nicely dressed,” he said.

The band worked five hours, 8 p.m. to 1 a.m. But when things got lively, they could be on the job till sun-up.

Joe recalled that “respectable uptown women” did not frequently visit the Big Casino. There was, however, a small area with a table near the bandstand where such patrons could sit, should they choose to enter.

Joe said he made good money at the casino until it burned. After it burned, he and his wife returned to California.

Though the Big Casino was rebuilt, Joe declined to work for the new owners (“Memories of the Big Casino,” Joe Andre, Central Nevada’s Glorious Past, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1998, pp. 23–24). Joe and his wife, Dorothy, eventually settled in Beatty, where they became owners of the famous Exchange Club.