Melvin Dummar dead: Supposedly rescued Howard Hughes in Nevada desert

Melvin Dummar won fleeting fame and a lifelong curse for supposedly rescuing Howard Hughes from the cold Central Nevada desert in December 1967, but he never saw a dime of the billionaire’s fortune, despite a disputed will that named him as a beneficiary.

Instead, Dummar worked hard at whatever jobs he could find, right up until the end.

Dummar died in Pahrump on Sunday, according to his family. He was 74.

“Melvin Dummar was a fascinating character because he was such a regular guy who got caught up in a really high-profile event,” said historian Geoff Schumacher, author of “Howard Hughes: Power, Paranoia &Palace Intrigue.”

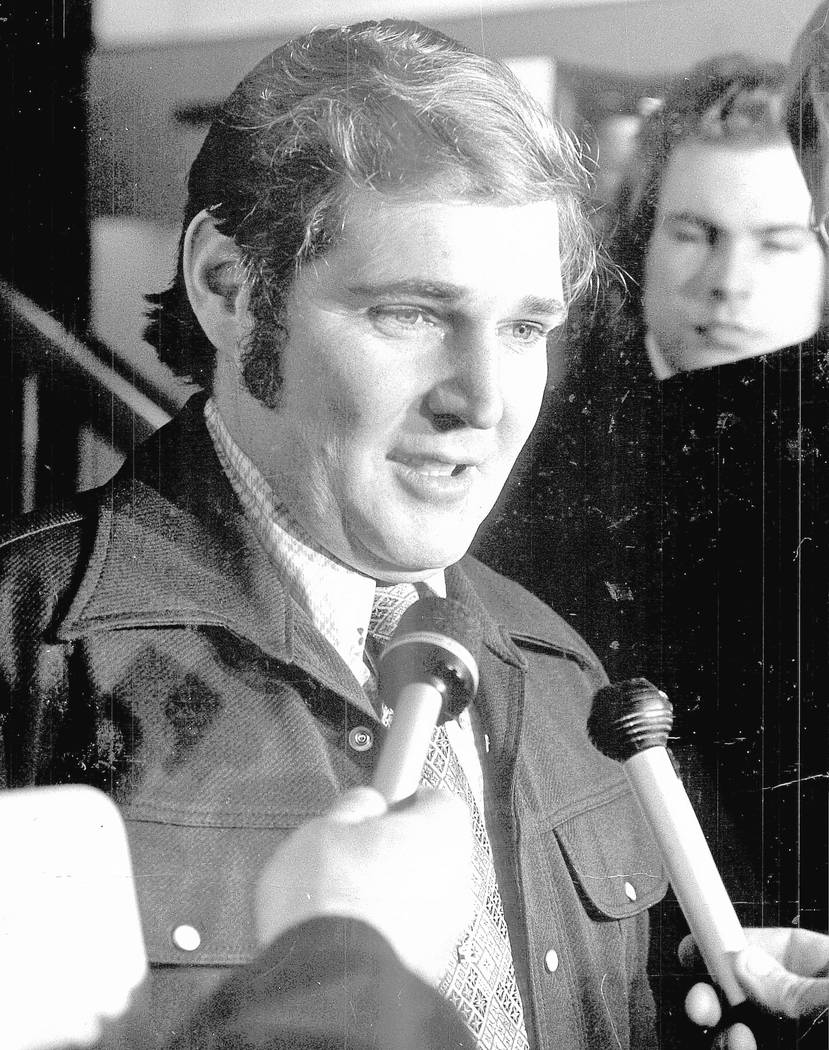

Dummar was hounded by reporters and mocked by Johnny Carson on the “Tonight Show,” after the so-called “Mormon Will” surfaced following Hughes’ death in 1976.

The mysterious document might have made the small town gas station operator a millionaire 100 times over had it not been dismissed as a fake by a Nevada court in 1978.

The story was later dramatized in the Academy Award-winning 1980 movie “Melvin and Howard,” but all the attention and suspicion nearly ruined Dummar’s life.

“The media pounced on Melvin at his little gas station in rural Utah,” said Schumacher, who interviewed Dummar several times for his book. “He talked about how he couldn’t get a job in Utah and was shunned by some people in his church and ultimately moved away because he couldn’t earn a dollar.”

As Dummar told the Review-Journal in 2006: “It almost killed me. It even drove me to the verge of suicide a couple of times.”

Still, he never wavered from his story about the night he picked up Hughes along U.S. Highway 95 about 160 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

Shot in the dark

Dummar claimed he was on his way to Los Angeles from his home in the Nye County town of Gabbs, when he pulled off the highway at around midnight to empty his bladder. That’s where he said he found a tall, thin man with a scruffy white beard and shoulder-length hair lying face down in the dirt.

He helped the shivering man into his car and drove him where he wanted to go: a back entrance of the Sands Hotel, which Hughes owned at the time.

“I didn’t ask him for anything. I didn’t expect anything,” Dummar said in 2006. “I didn’t even believe it was Hughes. I thought he was a bum.”

Dummar’s brother, Ray, believes the account of that night, though he still doesn’t know what to make of the Mormon Will and all of the drama that surrounded it.

“He picked him up. I know that part happened,” the lifelong Gabbs resident said. “From then on, it was kind of a fight.”

Schumacher doesn’t buy any of it.

Based on his research, he believes the Mormon Will was a forgery and that Dummar was mistaken about who he picked up in the desert that night.

Though Dummar’s account remained “incredibly consistent” over the years, Schumacher said it’s extremely unlikely that the famously reclusive and germophobic Hughes ever left his penthouse suite at the Desert Inn during the several years he lived there — let alone to fly around rural Nevada in a small plane to check out mining claims or visit a brothel as some have speculated.

“I believe Melvin Dummar picked somebody up. I don’t believe it was Howard Hughes,” said Schumacher, now the senior director of content at The Mob Museum.

Legacy of hard work

Ray Dummar said his brother had recently sold his home in Pahrump and moved into a smaller place in Beatty as he sought to get his affairs in order and make things easier on his wife, Bonnie.

He hopes his younger brother will be remembered simply as “a hard-working guy.”

“He was busy all the time,” Ray Dummar said. “He’s done every job there was around,” including selling frozen meat from the back of a truck.

He last saw his brother a couple of weeks ago, when Melvin swung through Gabbs while finishing a real estate deal. He was in the midst of his third bout with cancer and wasn’t getting around very well, but he was still working, Ray Dummar said.

As for all that stuff with Hughes and the will, Ray Dummar said it wasn’t something the family talked about very often.

“That kind of faded away,” Ray Dummar said.