A year later, low-level radioactive waste site fix near Beatty projected to be costly

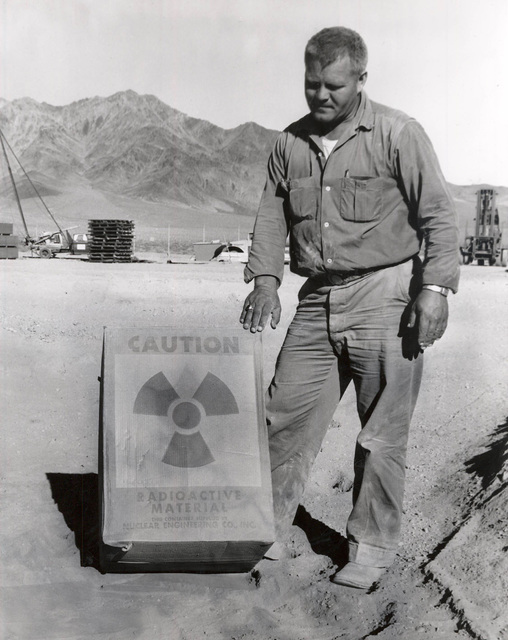

When Nevada inherited the closed Beatty low-level nuclear waste dump in 1997, it accepted $9 million from the company that had operated it for decades to ensure that the waste — some of it tainted with deadly plutonium — would remain safely buried for a century.

A portion of the money went for its intended purpose — “staff inspection time, the contractor, maintenance and repair of the site,” said Joe Pollock, deputy administrator for the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. But most was diverted to the state’s general fund over several legislative sessions and spent on other programs, he acknowledged in emails this week.

Now, a year after an underground fire at the dump triggered a series of violent eruptions that spewed hazardous debris 60 feet into the air, that “loan” is coming due.

And the bill to ensure there is no repeat of that frightening accident is expected to be much higher than $9 million.

The lessons of a year ago might also color the federal government’s continuing search for a place to entomb the nation’s highly radioactive waste from defense and commercial nuclear reactors.

Still under consideration for long-term storage of that dangerous waste is Yucca Mountain, less than 20 miles east of Beatty.

Leaky barrels and a rare rainfall

The accident that brought the state to this potentially costly crossroads occurred on Oct. 18, 2015, after days of heavy rainfall, a rare occurrence in an area that usually resembles a beige moonscape.

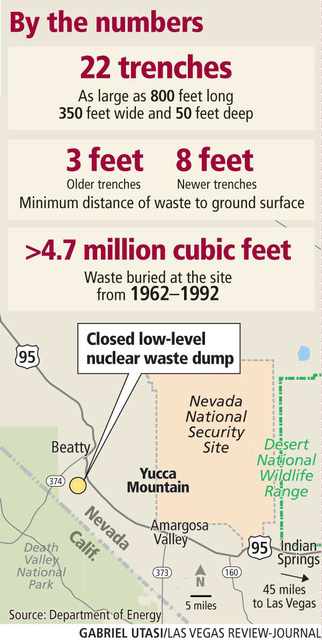

Authorities later concluded that moisture had penetrated a protective earthen cap covering Trench 14, one of 22 at the site, and had come into contact with metallic sodium in corroded steel drums.

Security officer Richard Stoddard, who works for US Ecology, the company that operated the dump when it was active and still runs the adjacent hazardous waste facility, later said he heard “what sounded like a sonic boom,” about 11 a.m. on that Sunday and saw a “black cloud of smoke rising from the west.”

He and site environmental manager John Dyer investigated but didn’t immediately see anything unusual. An hour later, however, they heard some “muffled small explosions and saw white smoke rising” from a hole along the maintenance shop road.

They called Bob Marchand, general manager for US Ecology, who arrived about 1:30 p.m.

“It was then that the largest explosion happened (and) we took cover,” Stoddard recalled in a statement included in a 305-page Nevada Department of Public Safety incident report.

Marchand used his cellphone from about 80 yards away to videotape the resulting spectacular-but-scary fireworks.

A bright orange-red fire erupted from a crater left behind by the big blast, emitting a plume of white smoke and “violently expelling” waste from the trench. A series of blasts hurled 11 radioactive waste drums from their graves, depositing two outside the fence that surrounds the dump 11 miles south of Beatty.

Authorities feared that pouring water onto the fire might cause more violent explosions, so they allowed it to burn into the night.

Concerns that the accident could have spread radioactive particles into the air prompted them to close a 140-mile stretch of U.S. Highway 95 — the state’s main north-south artery — for nearly 24 hours as they waited for the chemical fire to burn itself out. School was canceled in Beatty the next day.

No mention of plutonium

State officials made no mention of the presence of an estimated 47 pounds of highly radioactive plutonium and uranium isotopes amid the 7 million cubic feet of waste dumped at the landfill from 1962 through 1992.

Plutonium is believed to have arrived in small amounts at the dump. It was legally disposed of as low-level radioactive waste, which typically consists of low-risk items such as medical waste, contaminated clothing and laboratory equipment but can include very highly radioactive items in certain cases, such as parts from inside the reactor vessel in a nuclear power plant, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

It’s unclear whether any of this special radioactive material was buried within Trench 14.

Nevada’s Radiation Control Program, which took custody of the dump’s license from US Ecology along with 88 boxes of records about what was dumped and where, and the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health, which runs the program, declined to comment.

“For obvious security reasons, the specific location of radioactive materials, low-level or otherwise, is not something that the state will share beyond a need-to-know basis,” Pollock said.

Even NRC staff who visited the landfill in November at the request of state officials weren’t told where special materials like plutonium and uranium isotopes are buried.

“When we visited the site, they did not tell us where those materials are located,” said NRC civil engineer Doug Mandeville. “If I remember correctly, they had some sense of what the waste was in that portion (of Trench 14.) They wouldn’t want to put us in a situation where we would get exposed.”

‘I was terrified’

Hours after the fire and explosions, however, the whereabouts of potentially deadly radioactive materials was a primary concern for responders.

Federal aircraft and a Nevada National Guard team were dispatched to check whether any radioactive particles might have been released.

Maj. Nate Taylor led that four-soldier detail from the Guard’s 92nd Civil Support Team, which drove from Carson City in trucks equipped with the detection and decontamination gear, arriving in Beatty in the predawn hours of Oct. 19.

After surveying Beatty streets and finding no radiation above background levels, they headed to the dump.

Upon seeing Marchand’s video, “I was terrified,” he recalled “We didn’t know specifically what was in the ground. And we didn’t know … (at) a low-level radioactive storage facility what would be causing the earth to rise up like that.”

Three specialists in protective suits were sent in on an ATV – one each from the National Guard, a Las Vegas police task force and the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Remote Sensing Laboratory — to survey the 20-foot-diameter crater.

When they returned to the command post there was a collective sigh of relief. No radiation above background levels had been detected.

“It was a very awesome thing being able to come up empty-handed,” Taylor said. “A lot of times people are very excited to go do something real. But with the radiation, it’s really awesome not to find it.”

Cracks and quakes

By the end of the year, authorities had established a cause for the accident. Public Safety investigators concluded that cracks in the earthen cap allowed surface runoff to seep into where 116 steel drums of metallic sodium had been buried between 1969 and 1973.

The drums had been filled with oil to prevent water from contacting the metallic sodium, but corrosion allowed the oil to leak, leaving the material exposed.

“The reaction produced a large amount of heat and generated quantities of hydrogen gas,” state Fire Marshal Division Chief Peter Mulvihill wrote in the incident report. “The volume of gas produced caused the eruption of the ground, expelling dirt, buried and corroded drums, and the products of the sodium-water reaction, primarily sodium hydroxide.”

Most of the drums — 92 — came from a General Electric nuclear facility in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Twenty-two were from the Gulf-United nuclear facility in Elmsford, New York; and two were from the U.S. Bureau of Mines Research Center in Boulder City.

It’s not clear when the cracks in the cap occurred. State regulators had inspected the site April 13, 2015, just over six months before the accident. They noted that “previously reported cracks due to erosion and settling” had been repaired.

A report by the NRC’s Mandeville after his team’s visit in November speculates that “numerous smaller earthquakes with a magnitude range between 2 inches and 5 inches might have caused new cracks or widened ones that were already there.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s website bolsters that theory, showing that 21 earthquakes of magnitude 2.0 or greater and centered within a 35-mile radius of the Beatty dump occurred between the inspection and the accident.

The strongest, one of magnitude 3.4, occurred June 11, 2015. The second-strongest, of magnitude 2.4, occurred the day before the incident and was centered only 17 miles from the dump.

Action plan

At this point, no one knows how much it will cost the state to ensure that the Beatty dump doesn’t again threaten public health, but the meter is running.

Staff from the state’s Radiation Control Program and the Environmental Protection Division huddled early this year to hammer out an action plan to stabilize the site, then design and construct a cap capable of withstanding even historic rainfall and flooding.

A May 19 report shows the stabilization effort began a month after the incident, when the state contracted with US Ecology to gather debris ejected from Trench 14, repack it in oversized barrels and rebury it.

A sinkhole at another trench and more cracks in the cap were repaired. In addition, US Ecology scraped up 275,000 pounds of contaminated soil and disposed it in the adjacent hazardous waste facility.

The cost of the next phase of the retrofit will depend on what recommendations are made by a New Mexico-based waste management firm, Daniel B. Stephens and Associates, which recently signed an $89,304 contract with the state.

The NRC has recommended that trench caps should include plastic membranes made of high-density polyethylene to protect against water intrusion. Inline Distributing, an environmental remediation company in Sylmar, California, estimates it would cost $1.5 million for the material, not counting installation, to cover Trench 14. Covering the entire 40-acre site would run approximately $60 million.

A panel of 15 experts established by the state action plan will advise on the design of a more durable cap and a construction plan.

A preferred remediation effort will be put out for public comment this year, and a design and engineering contract will be awarded by September, followed by two years of construction. Funding must be approved by the Interim Finance Committee, a panel of 21 lawmakers who can approve funding between legislative sessions.

Whatever the eventual cost, it will not include money to remove the most dangerous waste – including plutonium – that found its way into the landfill.

The state “has no intention of relocating or removing those materials from the site,” Pollock said.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com. Follow @KeithRogers2 on Twitter.