Devils Hole tally: Pupfish population declining

AMARGOSA VALLEY — In the Nevada desert one mountain range removed from Death Valley, four divers strapped air tanks to their backs and slipped beneath the surface of a water-filled cavern for one of world’s most exclusive scuba expeditions.

The men brought along powerful lights and special cameras, but on this recent Saturday, they found surprisingly little of what they came to see.

“Where are all the fish?” asked Kevin Wilson, aquatic ecologist for the National Park Service, when he resurfaced about 45 minutes later.

It’s a question the protectors of the Devils Hole pupfish have been trying to answer for decades. The latest numbers, released in April, will only add to their sense of urgency.

The divers in the water and the experts at the surface counted just 87 of the critically endangered fish in the species’ only native habitat, 90 miles west of Las Vegas. That’s the lowest spring total in three years.

“We’re not in crisis mode. But we’re certainly concerned, and we’re actively working to improve the abundance of pupfish,” said Michael Schwemm, senior fish biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Southern Nevada.

A school of fish experts

The inch-long, neon-blue fish has been under federal protection since 1967. Its population peaked at 544 in 1990 and bottomed out at 32 in the spring of 2013.

The fate of the fish is in the hands of the Park Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Nevada Department of Wildlife. Experts from those agencies have identified a host of factors that could be contributing to the decline of the species, from predation and cannibalism to a lack of food and places for the fish to hide and lay their eggs.

“We all meet and discuss this stuff nearly weekly,” Schwemm said.

A year ago at this time, researchers counted 111 pupfish in Devils Hole, so 87 is “low but not shockingly low,” Schwemm said.

“It’s not out of the range of the natural variation that occurs over the seasons,” he said. “The fall count is typically higher, and we’re hoping to see a larger number when we record that in September.”

Counting the tiny fish is no simple task.

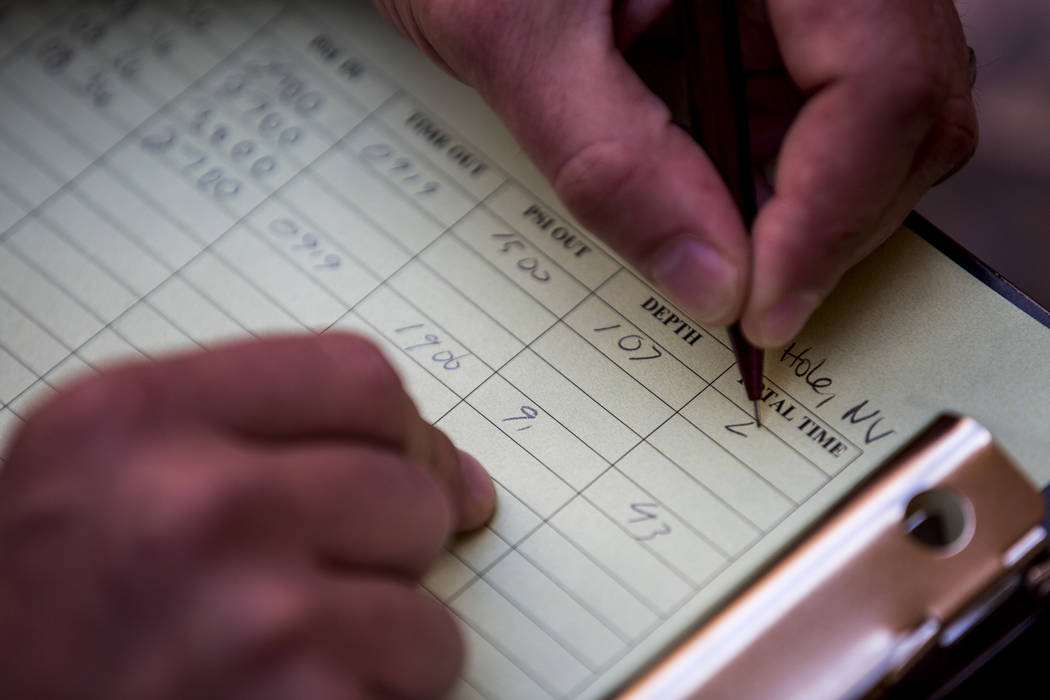

Though the species spends a lot of its time feeding and spawning on an algae-covered rock shelf right at the surface, divers must descend more than 100 feet in two-person teams to count the farthest-flung fish using a standardized search pattern that has been in use since the 1970s.

The population surveys are repeated several times over two days to ensure their accuracy.

Before the latest count began, members of the team offered predictions for what they would find — just a little friendly competition among colleagues with no real stakes involved.

“This is a government operation, so there’s no gambling,” Wilson joked.

The predictions ranged from 105 to 142, and they all proved to be overly optimistic.

“No one was even in the ballpark,” Schwemm said. “We all got surprised, and not in a good way.”

Growing reserve population

At least the team is seeing some success in the lab.

Biologists at the Ash Meadows Fish Conservation Facility, less than a mile from Devils Hole, have successfully established a reserve pupfish population that is now reproducing on its own in a 100,000-gallon refuge tank designed to replicate the species’ home in the wild, right down to its shape and temperature.

Olin Feuerbacher, aquaculturist for the facility, said the refuge tank has produced four successive generations of fish so far. He thinks there might be more than 100 living in the tank now, but he can’t know for sure unless he puts on scuba gear and gets lucky. Even in captivity, “they’re ridiculously hard to count,” he said.

A hundred lab-grown fish doesn’t sound like much of an accomplishment until you consider what it took to get this far. Because there are so few pupfish left in the wild, researchers are relegated to collecting single eggs from Devils Hole and trying to hatch and nurture the young in the lab.

“Kill one and 1 percent of the world’s population goes away,” Feuerbacher said.

With so little margin for error, nothing is left to chance.

For example, plans are now in the works to plant some native shrubs on the bare hillsides above Devils Hole in hopes of increasing the amount of organic material that finds it way into the water. But before any planting is done, researchers are painstakingly collecting and analyzing leaf litter from nearby shrubs of the same type so they can predict how much material they might end up introducing to the unique and isolated habitat the pupfish call home.

“We want to know as much as we can about everything that gets introduced to the system,” said Kerry Gold, the restoration specialist heading up the replanting effort.

So what has Gold learned so far? Even the plants around Devils Hole are “very, very hard to grow,” she said.

Living at the margins

As habitats go, Devils Hole is not very hospitable.

The water in the cavern 90 miles west of Las Vegas is thermally heated to a constant 93 degrees and carries barely enough dissolved oxygen to support life.

At the surface, Devils Hole is only about 8 feet wide and 60 feet long. The steep cavern walls shield the water from the sun for much of the year, which limits the growth of algae the native pupfish feed on and hide in to avoid predators.

Though the fish rarely descend below 100 feet, the water-filled cave goes down at least 430 feet into the ground. "It's not really known how deep the water system goes," said Jeffrey Goldstein, fisheries biologist and chief dive officer for Death Valley National Park.