‘I didn’t know life without the bombs’ says Nye County downwinder

Jeanne Sharp Howerton clearly remembers the nuclear tests.

All she had to do was step out on her front porch, where she’d have a direct line of sight to the detonation.

First, there was a flash.

“It was eerie,” she reflects. “There was just this huge flash and then it was really quiet. All the birds — everything was really, really quiet.”

Ten minutes later, the shockwaves would travel the 100 miles to rattle her family’s cattle ranch. Soon afterward, she’d see the mushroom cloud. “About half the time it would go over to Utah. And the other times it would come toward us.”

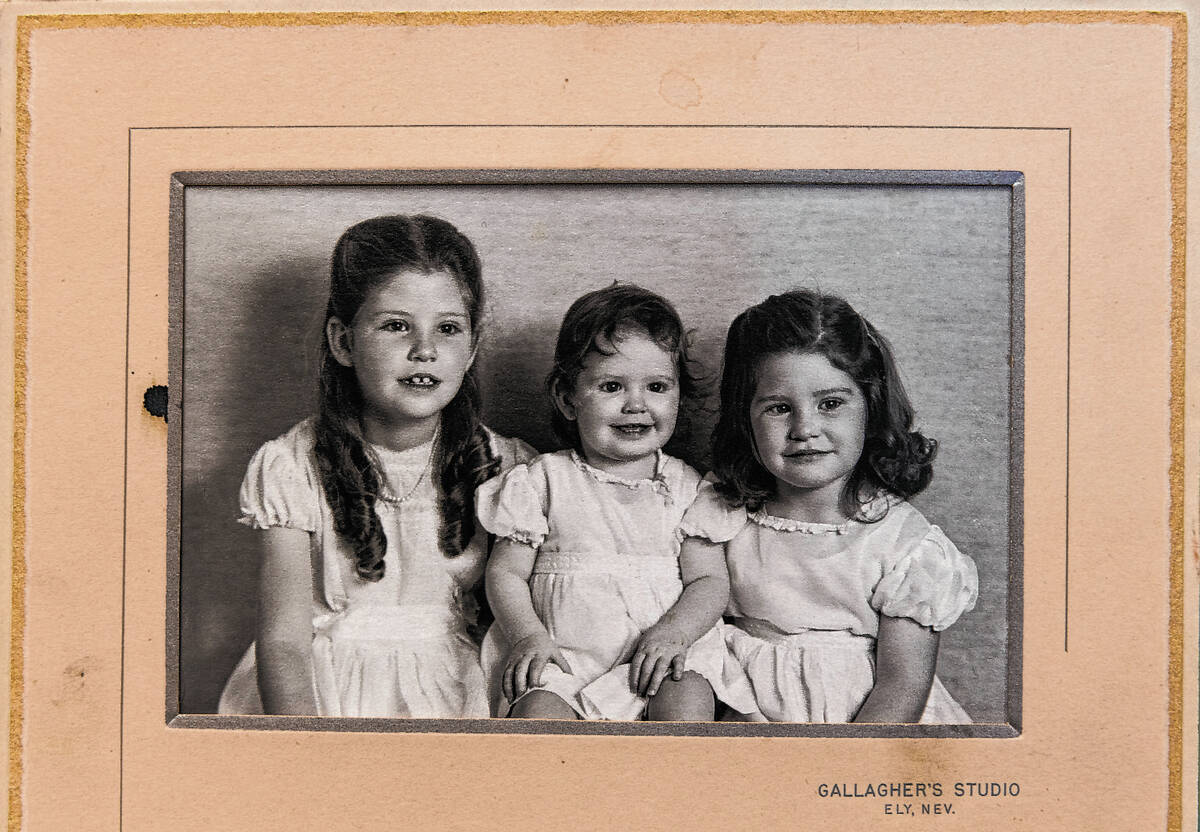

Sharp Howerton and her sisters would run inside until the dust passed. Then they could go about their day again — but “of course,” she adds, “the bomb had dropped radiation on everything.”

Sharp Howerton and her family are “downwinders,” people exposed to radiation from nuclear testing conducted by the federal government.

On June 25, she presented her visual memoir, “In the Dawn’s Early Light” at the National Atomic Testing Museum. In the presentation, she chronicled her family’s history in Railroad Valley and what it was like to witness nuclear testing growing up.

The family lived on the Blue Eagle Ranch in Nye County, about 100 miles north of what was then known as the Nevada Test Site. Between 1951 and 1992, the government conducted 100 atmospheric and 828 underground atomic tests at the site, now known as the Nevada National Security Site. The site is about 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

Joseph Kent, director of education at the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas, explains that the goal of these tests was to “improve the safety and reliability of the United States’ stockpile of nuclear weapons.”

He says the nuclear testing also served as a deterrent to all-out nuclear war with the Soviet Union and was a way to keep up in the nuclear arms race that extended through most of the Cold War. Kent adds that “most workers at the Nevada Test Site didn’t want any of them to have to be used.”

Growing up with nukes

Sharp Howerton, 75, has fond memories of her childhood on the ranch. “We had no power. We had no phone. We had no TV, no running water … But I absolutely loved the ranch.”

She liked to ride horses and listen to birds. She memorized poems and songs to pass the time. She invented games to play with her four sisters and invented pretend friends to keep her company. “You can also get a lot of mileage out of pretend friends,” she jokes.

Nuclear tests were just another part of ranch life for Sharp Howerton and her family. “I didn’t know life without the bombs,” she says. “The first one they set off January 27 [1951]. I was 4 years and 7 days old.”

Her mother would make the kids stay inside while the fallout passed over the house, but her father would often just put on a long-sleeve shirt and hat and go do his work.

The testing wasn’t distressing to Sharp Howerton at first. Her mother and father wouldn’t discuss the tests with the kids. When adults started talking about the tests, her parents would send the children outside to play.

In 1955, things changed. That was when a boy who lived 25 miles to the south — 25 miles closer to the testing sites — came down with leukemia.

“That was a changer. And then people started to get scared. People started to not be so happy about having these bombs.” The boy’s mother began circulating petitions to stop the tests. When people spoke out, though, Sharp Howerton says they were accused of being a part of a communist-inspired plot to sabotage the government.

“So then they kept doing [the tests]. And so we just accepted it and lived with it.”

The boy passed away before his 8th birthday in October 1956, and his family moved away afterward. Four years later, his father also died from cancer.

Sharp Howerton and her family stayed. People came around with pamphlets cautioning the family not to drink cow’s milk after a test. The fallout from the detonations would coat the grass the cows ate and end up in their milk, making it unsafe to drink.

She remembers men who came to check on the vegetables, the milk and the film badges the family wore to measure their radiation exposure. “They always said, you know, everything’s OK.”

Many of the family’s cattle developed eye cancer. People living closer to the site claimed their livestock received radiation beta burns. During one particularly notable test in 1962, Project Sedan, Sharp Howerton says the sky was so dark with fallout that the chickens went to roost.

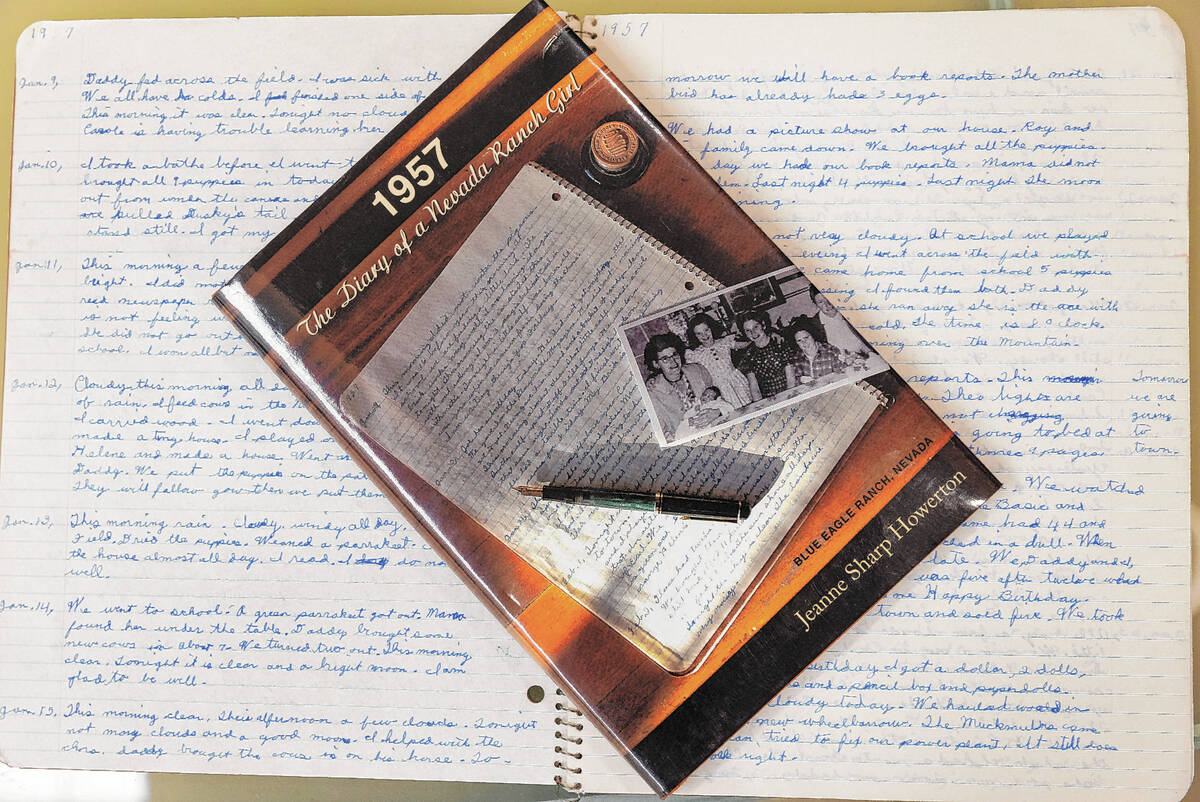

In 1957, Sharp Howerton started keeping her diary, a 25-cent spiral notebook she got for Christmas. The diary features first-hand accounts of daily life on the ranch — and information about nuclear detonations.

A July 19, 1957 entry reads: “We watched a rocket go off. It was a bomb. We saw the cloud.”

The notebook sat gathering dust until 2006, when Sharp Howerton stumbled across her old stuff and realized she had recorded information about the tests she saw. She was excited. “This is the story of not just my life, but my sisters’ lives and all the ranchers’.”

When she shared her stories with friends and family, they were so popular that she published her writings in 2014 in the book “1957: The Diary of a Nevada Ranch Girl.”

Testing underground, aftermath

One hundred atmospheric tests occurred at the test site between 1951 and 1963. With the signing of the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which prohibited nuclear weapons from being tested in the atmosphere, space or underwater, nuclear testing moved underground. Between 1963 and 1992, all nuclear device tests by the United States were conducted underground.

But Sharp Howerton says going underground with tests didn’t always stop the danger.

“Those bombs vented a lot more than you’d think,” she says. In 1968, she remembers fallout from a test floating toward her house like “big bunches of heavy clouds.”

An underground detonation in 1957 caved in the family’s well. “My dad had to go down into the well. More rocks fell in and a big rock fell down and just missed him. And so we went and got a lasso rope and put it under his arms and I wrapped it around the windmill and held it like you’d hold a calf, in case, you know, he collapsed into the water.”

The last nuclear test in the United States, Divider, happened on Sept. 23, 1992, at the Nevada Test Site. By that time, the government had conducted 928 nuclear tests and 1,021 detonations at the site.

In 1990, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), allowing people who lived downwind of atmospheric nuclear tests to be compensated if they or a relative developed certain cancers or illnesses after nuclear testing.

Downwinders receive $50,000 if they can verify their residence and have proof that they later developed one of the diseases covered in the act like breast cancer, thyroid cancer or leukemia. Under RECA, the Department of Justice has awarded more than $2.5 billion of benefits to over 39,000 claimants.

While it’s difficult to directly attribute any individual cancer to radiation exposure, exposure can increase cancer risk. For example, the National Cancer Institute has estimated that exposure to radiation from atmospheric testing at the Nevada Test Site might have caused or will cause anywhere between 11,300 and 212,000 thyroid cancer cases to develop across the country.

In Nevada, people living in Eureka, Lander, Lincoln, Nye and White Pine counties, as well as the northeastern edge of Clark County qualify for compensation if they can prove they lived in the area for 24 consecutive months between Jan. 21, 1951, and Oct. 31, 1958. They can also qualify if they lived in an affected area for the entire period from June 30, 1962, to July 31, 1962, which covers the period of Project Sedan and the four tests of Operation Sunbeam (also known as Operation Dominic II).

While RECA was set to expire in July, on June 7 the RECA Extension Act of 2022 was signed into law and extended the compensation program by two years. It’s now scheduled to sunset June 7, 2024.

Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, championed the RECA extension bill that passed with bipartisan support. “Downwinders and others harmed by the nation’s early atomic program often suffer the consequences of exposure decades after the fact. The passage of my RECA extension is a statement saying the United States government is not abandoning these victims and communities,” Lee said in a press release.

Sharp Howerton says both she and one of her sisters received compensation after being diagnosed with cancer. Another sister with thyroid problems — but not cancer — didn’t receive the compensation.

Although she doesn’t ask people if they’ve filed for compensation, she knows many people or their children would qualify.

At a recent family reunion, Sharp Howerton and her relatives got to talking about certain branches of their family tree. “Whatever happened to the miners’ kids?” they asked. “And then we found out that of the seven kids, five of them had died of cancer.”

Looking back

Reflecting on the tests, Sharp Howerton says she’s curious to learn about what happened at the Nevada Test Site. But she doesn’t feel angry.

“Imagine you have a frog,” she says, “and there’s a boiling pot of water on the stove. When you throw the frog in, it jumps out of the pot of water. But if you have a pot of water that’s cold and you put the frog in and then you heat it up, the frog will cook to death because he doesn’t know that there’s danger and it happens so slowly. That’s kind of like how we were.”

She’s spoken quite a bit with her sisters about the tests, but those talks are often inconclusive. “We didn’t have terribly negative thoughts about them. And I guess I still don’t even know.”

But she adds, “I do know that what they did was pretty bad to do to your own people. And I guess we needed to do it. But the world’s a dangerous place.”

Colton Poore is a 2022 Mass Media reporting fellow through the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Email him at cpoore@reviewjournal.com or follow him on Twitter @coltonlpoore.