Prehistoric building blocks of the Pahrump Valley

“For me, what’s most fascinating about the universe is that it’s knowable.” — Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist, Director of New York’s Hayden Planetarium

In this column, I will attempt to give a brief overview of the origins of the Pahrump Valley. Starting at the very beginning, I will try to show how it got here according to science.

The universe is very old and very large. It wasn’t that long ago that scientists believed the universe consisted of one galaxy—the Milky Way—where the sun, the earth, and the stars visible to the naked eye in the night sky reside.

Astronomer Edwin Hubble was the first to recognize that the universe consists of more than one galaxy. The Hubble telescope, named after him, has been orbiting the earth at 17,500 miles per hour for the last 25 years.

It has helped revolutionize our view of the age and size of the universe and represents one of humanity’s greatest scientific achievements.

Thanks to research made possible by the Hubble telescope, we know that the universe is 13.8 billion years old and is composed of a vast multitude of galaxies.

In fact, the Hubble focused for 10 days on a small sliver of space equivalent to the width of a dime at a distance of 75 feet, and what it found was mind-blowing. Visible within that small viewing area were more than 1,500 galaxies extending to the edge of the universe.

Galaxies, of course, are composed of enormous numbers of stars. And in stars, with their immense heat, the many elements that make up the universe, from lithium to uranium, are cooked—that is to say, formed out of hydrogen.

When stars die, their contents are scattered into space, where they eventually accumulate into new stars in which more elements are cooked and then dispersed. Out of this stardust, new stars and their planets are formed.

All the elements that make up the earth, including the Pahrump Valley and its adjoining mountain ranges, were made in this way. They were produced in stars and scattered into space.

About 4.6 billion years ago, stardust and gas accumulated to form our sun and its planets, including Mercury, Venus, Earth, and the other five planets; the planets’ 140 moons; the asteroid belt; and so on.

As the newly formed earth solidified, it developed a hot interior and a hard rock crust. The crust was composed of many separate and distinct pieces. Some were low-lying and formed large basins that held oceans.

Others lay at higher elevations above the basins and are known as continents. Driven by forces deep within the earth, all the pieces, both those lying under the oceans and those at higher elevations, continuously moved (and continue to move) about over the earth’s surface through time.

About 270 million years ago, all the world’s continents were assembled together in one single “supercontinent” called Pangaea.

About 215 million years ago, Pangaea began to break up as the continental plates moved apart. The plate that became North America began moving west across the earth’s surface.

As it moved, it slid over the adjoining ocean plates and gathered pieces of continental material and debris off the tops of the ocean plates. This material accumulated on the western margin of the North American continent much as snow accumulates before a snowplow’s blade. The ocean plates were forced down, sliding under the westward-moving continent.

Between 180 million and 20 million years ago, one such ocean plate, the Farallon, was forced, or subducted, under the westward-moving continental plate.

As the Farallon plate was forced down into the earth, melting occurred and great plumes of melted Farallon plate rose to the earth’s surface producing the Sierra Nevada’s volcanoes and granite masses, bringing gold, silver, and other valuable minerals upward, which of course eventually resulted in the California gold rush that began in 1848.

As the Farallon plate was subducted under the continent, a “slab gap” was created when the descending Farallon plate split into two parts.

The gap exposed a portion of the continent’s western area to great heat from the earth’s interior, causing that part of the continent lying above the slab gap, which was up to 170 miles across, to stretch and become thin.

About 20 million years ago, this stretching and thinning created the Basin and Range surface features found across Nevada and parts of California, Utah, and Idaho.

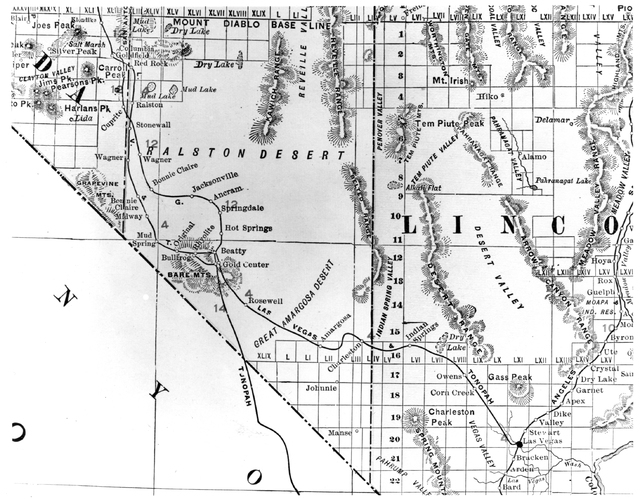

Great blocks of the earth faulted and broke due to tension and pulling apart, leading to the formation of north-south trending valleys and parallel mountain ranges. The Nopah Range on the west and the Pahrump Valley itself were formed in this way. Mount Whitney (14,494 feet) is the highest point in the basin and range system, while Death Valley (282 feet below sea level) is the lowest.

Because of compressive forces about 40 million years earlier, the Spring Mountains adjoining the Pahrump Valley on the east, whose highest point is Charleston Peak at 11,912 feet, were formed by a thrust fault where blocks of rock are thrust over adjoining formations.

Though little water now accumulates in the Nopah Range, in ages past volumes were no doubt greater. Over the past millions of years, the Spring Mountains and Charleston Peak have received considerable precipitation.

Water running off the range washed large amounts of eroded debris into the Pahrump Valley. Great fan-shaped formations of accumulated debris, known as alluvial fans, can be seen extending from the mouths of canyons to the valley below. Snow and rainwater running off the west side of the Spring Mountains accumulated in the fans and beneath the surface in the Pahrump Valley.

Water that accumulated beneath the alluvial fans and valley floor flowed from numerous springs that became the basis of human activity in Pahrump Valley.

These water sources made it possible for Native Americans to occupy the Pahrump Valley beginning several thousand years ago, most recently, the Southern Paiute. In the 1870s ranches were established at major water sources in the valley, including the Yount Ranch developed by Joseph and Margaret Yount and their family at Manse Springs starting in 1876.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Bob McCracken has a doctorate in cultural anthropology and is the author of numerous books in the Nye County Town History Project, including a history of Pahrump.