Bottle House endures over a century

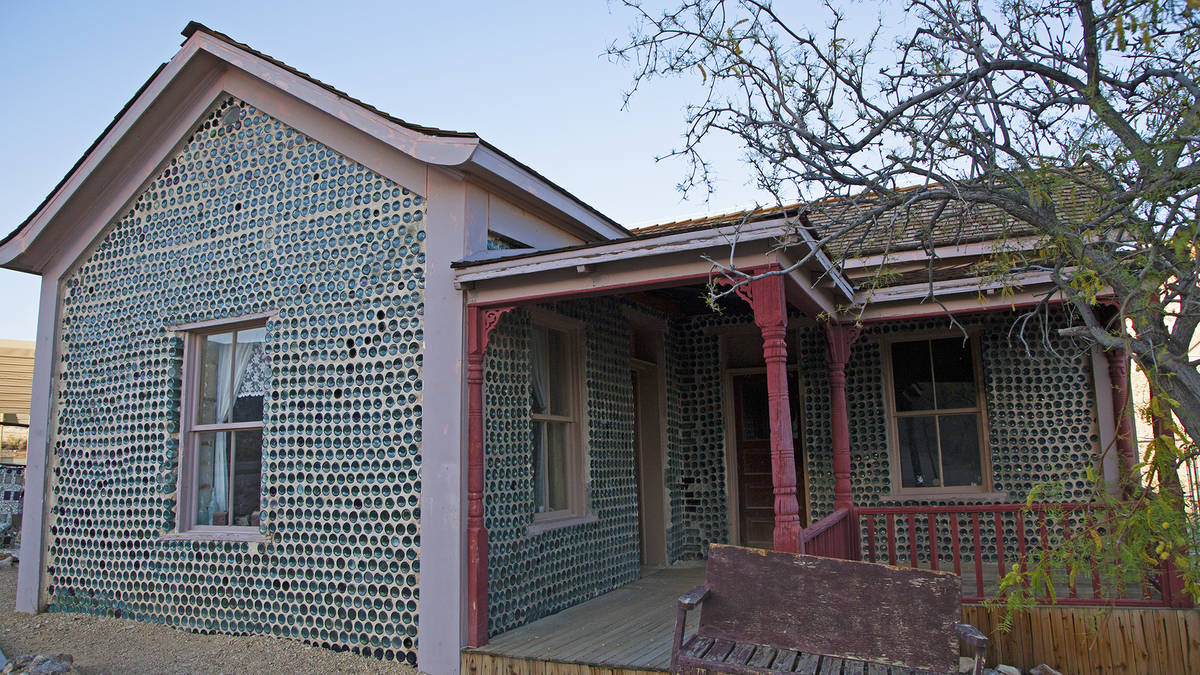

When 76-year-old Australian immigrant Tom Kelly built his bottle house in Rhyolite, Nevada, he probably had no idea that it would outlast practically all the other structures in the mining town, or that it would be a popular tourist attraction well over a hundred years later.

Bottle houses were not uncommon in mining towns, where hard-drinking miners drained plenty of beer and spirit bottles, providing an abundant supply of building materials. According to some accounts, there were two smaller bottle houses in Rhyolite, but no trace of them remains today.

At least one online article claims that Kelly was a saloon keeper, giving him ready access to bottles, but most accounts describe him as a miner. The 1900 census found him in Oregon, and he gave his occupation as bricklayer.

In the 1910 census, he is listed as widowed, living on Golden Street in Rhyolite, and as a mason. He was living in Eureka, Nevada by 1920, and died in Yerington in 1928 at the age of 95. He is buried in Eureka.

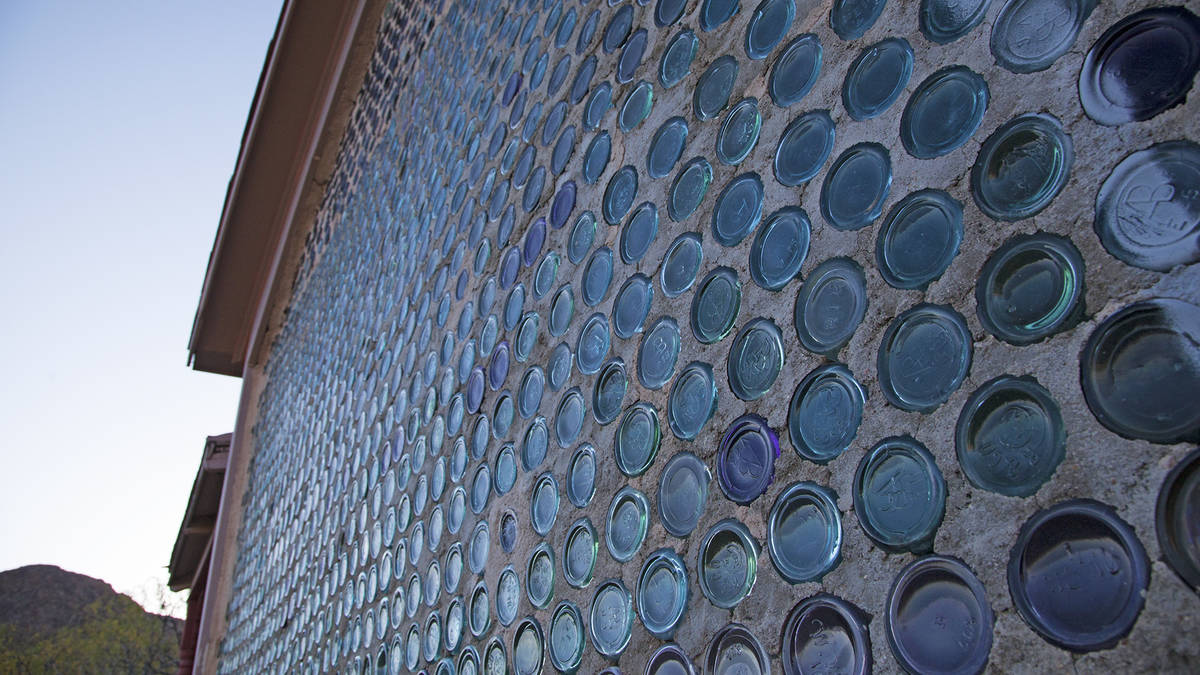

Although some have estimated that he used as many as 50,000 bottles in constructing his bottle house, the most common estimate is in the neighborhood of 30,000. It is difficult to make an accurate count, since the structure reportedly has a double bottle foundation, which is not visible.

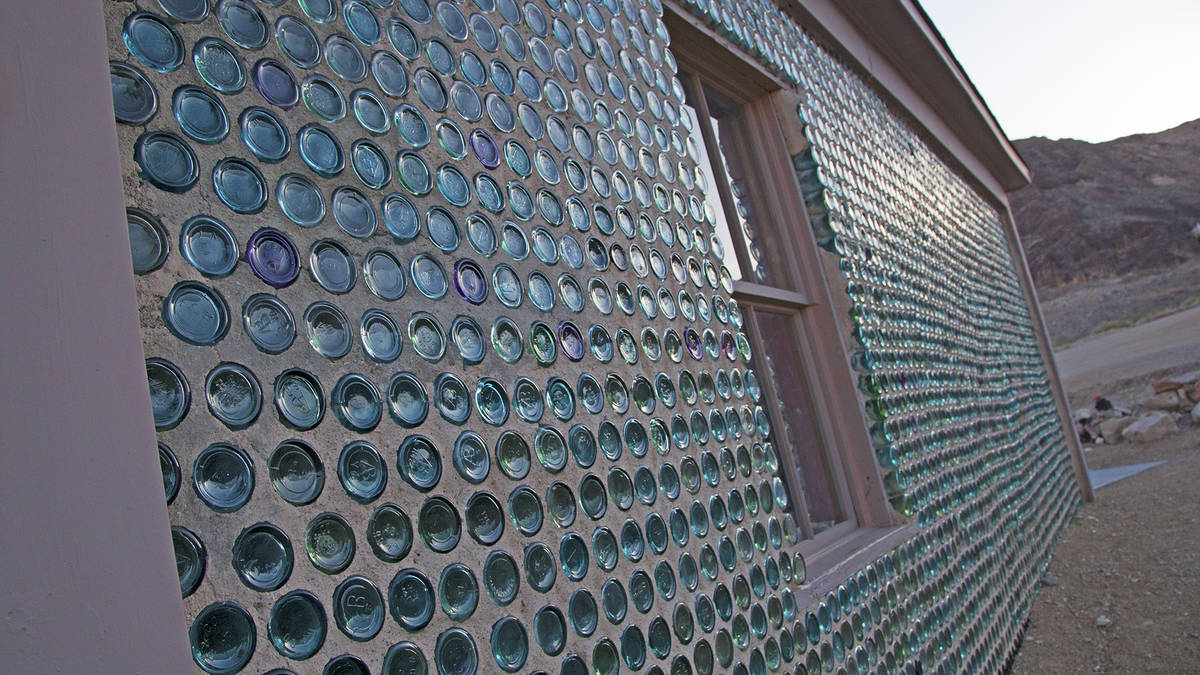

The majority of the bottles are beer bottles, many of which bear the letters “AB” on the bottom, for brewer Adolphus Bush. But there were quite a few other bottles of the same size that once held mineral water, and some of the smaller bottles held medicine, such as bitters.

The wall is thicker than the length of the bottles, being plastered over inside, so that the interior walls give no hint of what is inside them. The hollow bottles provide some level of insulation, reportedly keeping the interior 20 degrees cooler in the summer and 15 degrees warmer in the winter; although the last person to stay in the bottle house, Evan Thompson, said that in the winter he slept fully dressed, under heavy quilts, with heated irons and hot water bottles.

Kelly mortared the bottles into the wall with adobe that he made using local dirt. That he didn’t wash them is evidenced by residue that can be seen inside many of them. In fact, one of the bottles contains the “Rhyolite mummies.” These are not human, of course, but the white, mummified remains of crickets that were trapped in the bottle when he sealed it into the wall.

Each of the three rooms in the house has its own door. There is a covered front porch and a front walkway made by burying bottles bottoms up in the ground. Kelly also finished the house off with gingerbread-style trim.

Kelly began construction on the bottle house in September, 1905, and finished it in February, 1906. He then raffled it off, selling tickets for $5 each.

Reportedly, the Bennet family, winners of the raffle, lived in the bottle house until 1914, at which time almost the entire population of Rhyolite had moved away.

The bottle house then apparently sat idle and unoccupied until 1925, when Paramount Pictures did some restoration work on it, including a new roof. They used it in the filming of two movies: “The Airmail,” and “Wanderers of the West.”

Afterward, Louis Murphy and Bessie Moffat operated the bottle house as a sort of museum, with Murphy giving tours to tourists and selling gift items.

Murphy died in 1956, and the Beatty Improvement Association invited the Tommy Thompson family to move to the property and take care of the house. Tommy was a musician and former carnival worker. He filled the interior with some colorful props to spice up the tour he offered to tourists. Tommy and wife Mary were responsible for building the miniature village adjacent to the bottle house.

Their grandson, Evan, whom they raised as a son, continued operation of the bottle house as a tourist attraction and gift shop until he moved north of Beatty in 1989.

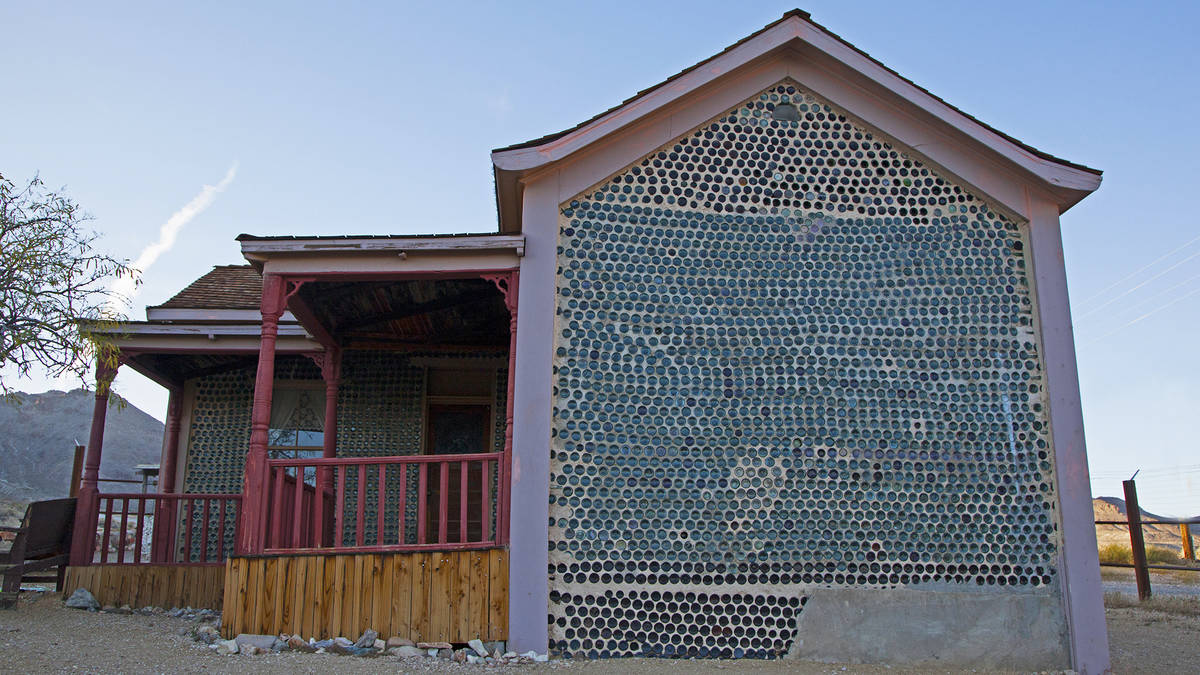

At this point, the bottle house was suffering definite deterioration. There was a hole in the south wall where one or more people had dug out bottles. The roof was in bad shape, and part of the front wall near the peak of the roof had collapsed inward, with bottles falling into the attic space.

The bottle house next came to be cared for by the Bureau of Land Management, which arranged for volunteer caretakers to live on the property to keep an eye on it.

Volunteers from the Friends of Rhyolite and the Beatty Museum patched the roof with donated materials, and helped to remove the bottles from the attic so the BLM could put them in storage for possible use in repair. (Amazingly, some of the mineral water bottles put in storage still had their perfectly preserved original paper labels attached.) A large plywood patch was nailed in place to cover the part of the wall that had caved in.

The south wall was seriously in trouble, as it had begun to tilt outward and was in danger of collapsing. The BLM covered most of that wall with a buttressed wooden brace to keep it from falling.

Eventually, they managed to refurbish the structure, including a new shake shingle roof. They hired experts who managed to match Kelly’s adobe mixture well enough to blend in.

To strengthen and preserve the bottle house, before replacing the wood trim around the outer walls and at the corners, they added a welded steel framework to hold the building together. This is totally hidden under the wood.

They also contoured the parking area in front of the Bottle house to channel rain water away from the building.

The bottle house is now surrounded by a high security fence to discourage vandalism and theft. During the pandemic the gate has been kept locked, but visitors can view the bottle house through the fence. An on-site caretaker watches over the bottle house and the rest of the ghost town, and, when the world opens back up again, he will once more be able to unlock the gate.

Richard Stephens is a freelance reporter living in Beatty.