Spring Mountains lag behind rest of state with unusually low snowpack numbers

The seasonally snowy mountain range to the east of the Pahrump Valley isn’t just a beautiful feature of the desert landscape: It’s a lifeline in the harsh Mojave Desert.

For rural Southern Nevadans who live outside the range of pipelines from Lake Mead, that snow will soon melt into drinking water — the necessary fuel for life in the desert. It is the only source of recharge for Basin 162, which encompasses Pahrump.

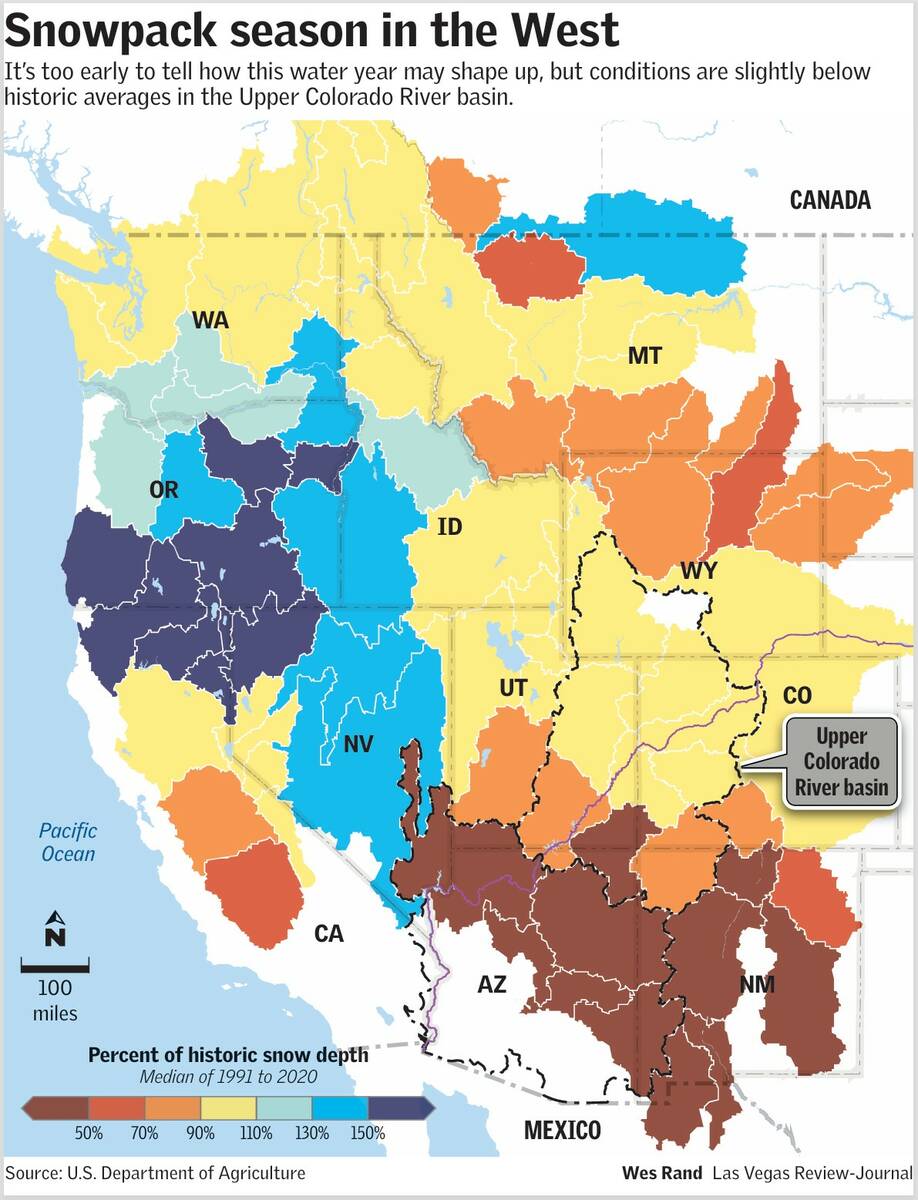

With snowpack in the Spring Mountains at zero percent of a historic median as of last week, some may worry about the future of a region where some are already being forced to drill wells deeper to meet a declining water table. Southern Nevada’s mountain range is far behind Northern Nevada, where all of its basins are well above 100 percent of the historic median.

Baker Perry, Nevada’s state climatologist and professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, said such low numbers are unusual for the Spring Mountains at this point in the year.

“The fact that there’s really no snow on the ground is a real concern right now,” Perry said. “The good news is that we’re still relatively early in the season, and a pattern change is looking more probable.”

‘This is not something to worry about’

There’s no immediate cause for alarm, said Dann Weeks, general manager of the Nye County Water District.

“Anybody who’s lived here knows this is not something to panic about,” Weeks said. “It takes hundreds and hundreds of years for the water that falls on a mountain to make its way down to a basin for withdrawal. A single dry year doesn’t have a direct impact.”

As dictated by the state engineer, the most water that can be drawn out from Basin 162 is 20,000 acre-feet. One acre-foot of water is about enough to sustain two single-family homes for a year.

The basin is over-committed with too many distributed rights to pump water, though it continues to be under-pumped, Weeks said. Though the nation’s driest state is trending drier and hotter due to climate change, any negative effects are likely to be seen much further down the line.

“It’s going to be a dry year, but it’s not anything to worry about,” Weeks said. “Dry and wet years alternate.”

Ski season, Amargosa River affected as well

The Lee Canyon Ski Resort on Mount Charleston employs snowmaking technology to keep its surfaces white in the winter.

Josh Bean, the resort’s director of mountain operations, said in a statement that artificial snow allows four of the five ski lifts to remain operational.

Lee Canyon received 215 inches of snow last season, Bean said, and the 2022-2023 season proved to be a record-breaking year with 266 inches.

“Seasonal variability is part of the ski industry,” Bean said. “Warm, sunny winter days are popular with many locals, so we are seeing a strong turnout, especially from those learning to ski and snowboard.”

For one of the nation’s least known rivers, the Amargosa, low water availability over time may have a dramatic impact, said Mason Voehl, executive director of the nonprofit Amargosa Conservancy.

The largely underground river, which flows from Beatty down into Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park, is the lifeblood of the many people and animals who live along it.

Nye County is making strides in improving water infrastructure, with investments in cloud-seeding technology and $14 million awarded from the Water Resources Development Act of 2024 for wastewater treatment and a water wellfield and pipeline.

However, as Nevada’s climate becomes more extreme, less water availability is inevitable, Voehl said.

“What climate change is doing — that’s going to become very real very quickly,” Voehl said. “There’s going to be a lot of heartache.”

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.