Nevada ditches caucuses for primary, but details still cloudy

Few involved with Nevada’s presidential caucuses will weep after the bipartisan deathstroke delivered by the Nevada Legislature last month, and for good reason: They will be quite busy working to ensure the Legislature’s far bolder move of making Nevada the first state to weigh in on presidential nominations comes to fruition.

“The campaign is now coming together,” said Alex Goff, one of Nevada’s Democratic National Committee members. “In the summer, we’ll start calling the other committee members to make our push.”

While Assembly Bill 126, one of several major voting reforms passed in the 2021 session, clearly states Nevadans will vote their presidential preference in a secret-ballot primary on the first Tuesday in February, Goff and everyone else involved in the process understand that the national parties have the ultimate say in setting the nominating calendar.

“There is flexibility in the legislation,” Goff said. “Speaker Frierson put it together so we can take advantage of the opportunity. I don’t think we’re going to do any sort of power play to force our way first, because we have a good argument.”

Goff and his fellow Nevada Democrats have begun making that argument publicly and privately, with a particular focus on the two states that have traditionally voted ahead of Nevada: Iowa and New Hampshire.

Nevada has a far more diverse population, they’ve said, in terms of race and ethnicity but also in educational background and union membership. It is younger and a swing state in the emerging West, where Democrats have made recent strides while losing ground further east.

The DNC appears poised to hear the diversity argument, particularly after Iowa Democrats botched their first-in-the-nation caucuses in 2020, though no official movement is expected until next year at the earliest.

But many hurdles for AB 126’s signature move remain.

Gov. Steve Sisolak has yet to sign the bill, though he is expected to. His office did not respond to a request for an update on his plans.

The bill also affects state Republicans, who are less inclined to rock the boat on the nominating calendar.

Nonpartisans and third-party members, whose combined numbers have already overtaken Republicans and may soon due the same to Democrats, remain boxed out of the entire process.

Iowa and New Hampshire will fight the change, and South Carolina — the fourth state on the calendar and home to the Democratic National Committee’s new chairman, Jaime Harrison — is likely to match Nevada’s diversity push.

“We have to work really hard to get the DNC to understand that times have changed,” said former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. “Just because (Iowa and New Hampshire) have gone first for a long time doesn’t mean they’re entitled to it now.”

The push

Reid, who played an integral role in moving Nevada to its current third-in-the-nation status, praised the Legislature’s work in passing AB 126 and AB 321, which made the state just the sixth in the country to adopt universal mail-in voting.

Goff stressed the importance of the second part. While many other states including Iowa and New Hampshire, he said, are discussing limiting voting access, Nevada has greatly expanded it during its most recent session. The Democratic National Committee has made passing similar federal legislation a top priority.

“It puts us in a good light,” Goff said.

Goff noted Reid, Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, the first Latina elected to the U.S. Senate, and Rep. Steven Horsford, a rising member in the House’s Black Caucus, will all be key in state Democrats’ efforts to sway a national committee vote in Nevada’s favor.

When asked if he had begun work on the matter, Reid deferred to Sisolak.

“I am looking for leadership from Governor Sisolak,” Reid said. “He will tell me when to make a few calls, and I am happy to do whatever I can.”

Like Reid, the progressive-led Nevada State Democratic Party is thrilled with the death of the caucuses and the push for Nevada to vote first.

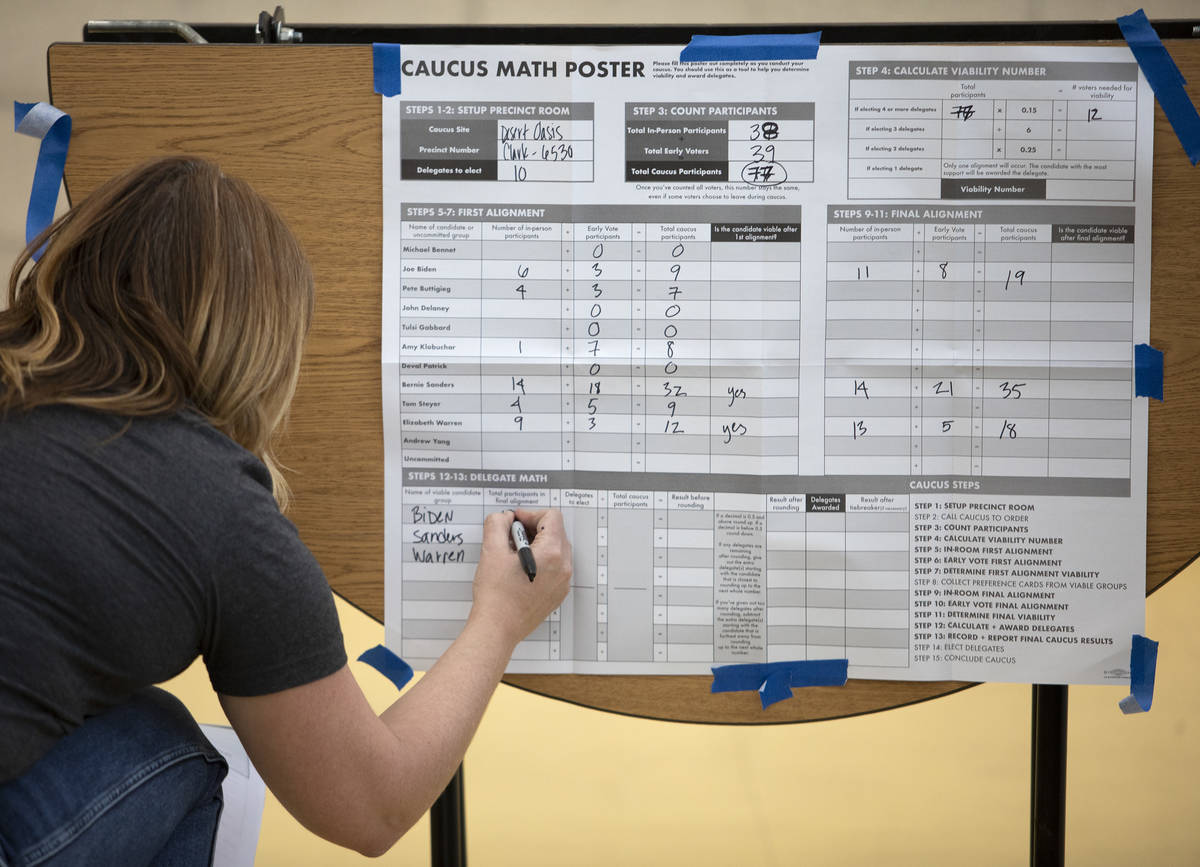

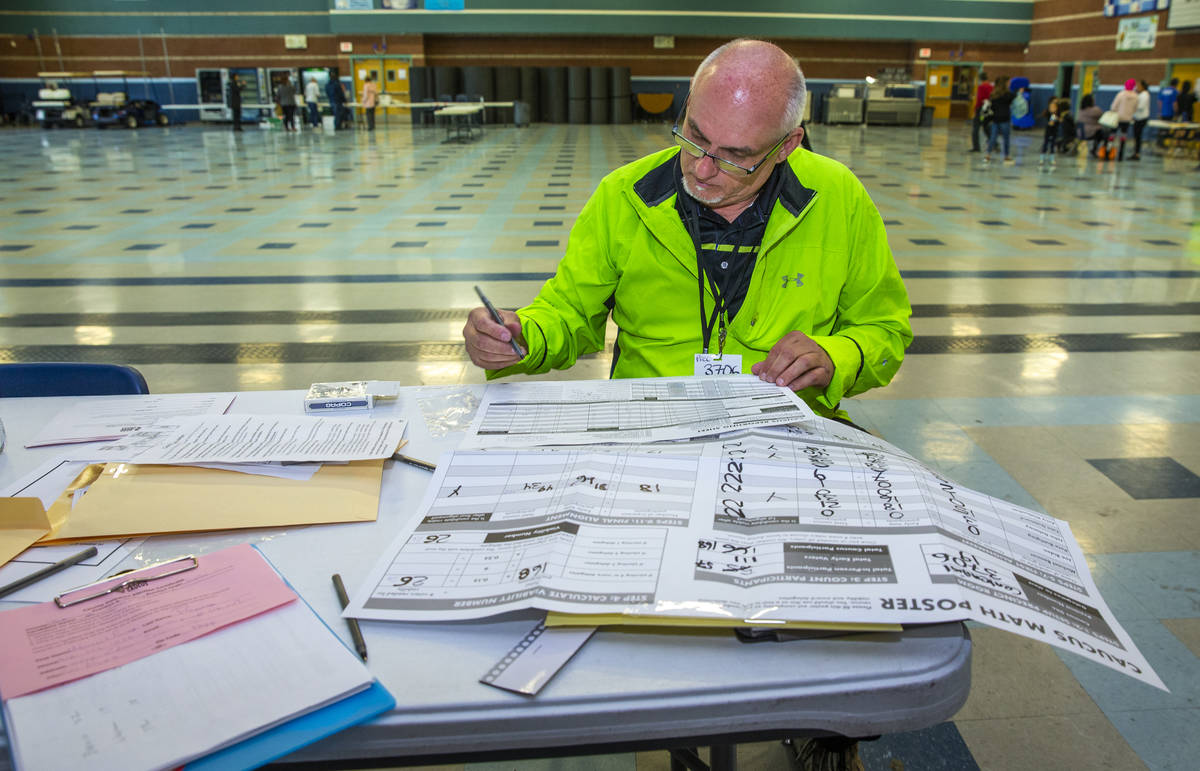

“We won’t miss the excruciating process of training of 2,000 volunteers for the caucuses,” Executive Director Chris Klarich said. “They’re confusing and lead to decreased participation.”

Klarich said the state party applauds the expansion of voter access and will do what it can to support the state’s case to national Democrats. Any changes to the party’s nominating plans will not happen in 2021.

“(The DNC is) going to continue to let the process play out, as it does every four years, and look forward to hearing the insight and recommendations from all interested parties on the 2020 reforms, and on the 2024 calendar at the appropriate time in the process,” Harrison said in a statement.

Nevada Republican Party Chair Michael McDonald told the Review-Journal in February he would also like to see Nevada move up on the nominating calendar, but he stressed the importance of doing so through cooperation with his own national party.

“Our position has not changed,” McDonald said in a statement Thursday. “We are working with the national party and the other carve out states to resolve any potential conflicts and to ensure that Nevada remains first in the West.”

Like the DNC, the Republican National Committee will not vote on its nominating calendar until 2022 at the earliest.

New Hampshire unfazed

New Hampshire has its own state law on when its primary should be held: “The presidential primary election shall be held on the second Tuesday in March or on a date selected by the secretary of state which is seven days or more immediately preceding the date on which any other state shall hold a similar election, whichever is earlier, of each year when a president of the United States is to be elected or the year previous.”

For 45 years, that secretary of state has been Bill Gardner, and he has moved his primary up as other states have done the same. It was held on Feb. 11 in 2020.

Asked for his reaction to Nevada’s new law, Gardner was direct.

“We’ve been dealing with Harry Reid for over 50 years now,” Gardner said. “We’re just waiting for him to run out of steam.”

Gardner recounted Reid’s own attempt, as a young Nevada assemblyman in 1969, to push Nevada ahead of New Hampshire in the voting order. Gardner said Reid and other Democrats were dissatisfied with the 1968 presidential election, in which little-known Sen. Eugene McCarthy nearly defeated incumbent President Lyndon Johnson in New Hampshire’s primary with an anti-Vietnam War platform.

Johnson withdrew from the race before another state held a primary. Democrats eventually selected Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, who was crushed in an electoral college landslide by Richard Nixon.

“Our primary is for the little guy,” Gardner said. “It’s easy to get on the ballot here, and the parties don’t like that.”

The 1969 Nevada bill, AB 200, passed both legislative houses before meeting its end through a veto from then-Republican Gov. Paul Laxalt.

“This bill seeks to displace a sister state, New Hampshire, from its traditional role of conducting the first presidential primary,” Laxalt wrote in his veto. “Its leaders have indicated that if this bill is approved, they will reset their date ahead of Nevada.”

Had Sisolak not defeated Laxalt’s grandson, former Attorney General Adam Laxalt, in the 2018 gubernatorial race, the younger Laxalt may have found himself in position to write the very same veto half a century later.

Asked if he will make good on his state’s 52-year-old promise and simply move New Hampshire’s primary to January in response to Nevada’s new law, if signed by Sisolak, Gardner said it was too early to tell.

Reid admitted he had worked on moving Nevada up for a long time. Asked if the time was finally right for the move, he doubled down.

“The time was right a long time ago,” Reid said. “But we haven’t been successful.”

Nonpartisans now paying to be excluded

The caucuses may be dead, and Nevada may end up voting first, but one aspect of the state’s election code will remain constant: One-third of its electorate are still not welcome to participate in presidential primaries.

Doug Goodman, founder and executive director of Nevadans for Election Reform, advocates for nonpartisan and third-party voters — who, combined, make up 33 percent of Nevada active registered voters ahead of 31 percent for Republicans and behind 36 percent for Democrats. The group will likely reach 40 percent of the electorate by 2024 if trends continue, Goodman said.

Goodman noted that unlike caucuses, which are privately funded by the parties, a closed presidential preference primary will be paid for by the taxpayers. The Nevada secretary of state’s office estimated the change will cost about $5.2 million in the 2023-24 biennium.

“Nonpartisans now pay for both parties’ primaries through taxes, but we can’t participate,” Goodman said. “I can understand the desire to keep it to party members, but they should have opened them up to all voters.”

Goodman said Republicans and Democrats view the closed primary system as a recruitment opportunity, and that plan may prove effective with the switch to primaries in 2024. But it misses the larger point made by the steady recent rise of nonpartisan voter registration in the state.

“If someone wants to vote in the primary, they can just switch parties,” Goodman said. “But we’ve seen that doesn’t happen. People are frustrated with the parties.”

Republican state Sen. Ben Kieckhefer, R-Reno, introduced a bill in the 2021 session of the Legislature calling for a “blanket” primary, where voters could choose any candidate regardless of political party, but that measure died in committee without getting a hearing.

Contact Rory Appleton at rappleton@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0276. Follow @RoryDoesPhonics on Twitter.